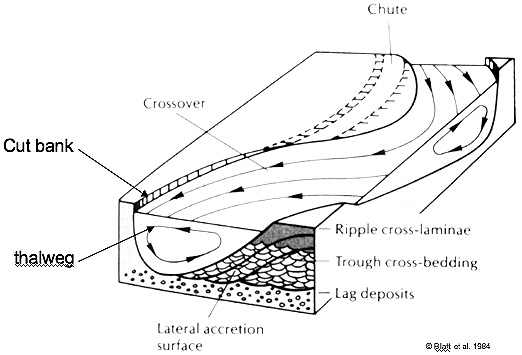

The thalweg line is a concept of river law, defined under customary law either as “the mid-line of the main navigation channel” or as the deepest water line. The purpose of the thalweg line in matters of delimitation is to ensure an equal share of the navigable channel between two sovereign States taking into account the navigation interests. As compared to the median-line, the thalweg line as single rule was less used for maritime delimitation in State practice; one example is the Alaska Boundary Arbitration between Great Britain and the United States in 1903.

View More what is the meaning of Thalweg LineCategory: Law of the sea

The law of the sea is a body of customs, treaties, and international agreements by which governments maintain order, productivity, and peaceful relations on the sea. NOAA’s nautical charts provide the baseline that marks the inner limit of the territorial sea and the outer limit of internal waters.

what is the meaning of single maritime boundaries line (single line with dual purpose or all-purpose line)

In theory, the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone could follow a different line than the continental shelf. For practical reasons, however, states seem to have wanted to have their maritime zones delimited by a single maritime boundary for all purposes. The reason for this lies first of all in the shared overlap of natural resources between the two zones.

View More what is the meaning of single maritime boundaries line (single line with dual purpose or all-purpose line)Three-stage Approach of Maritime Delimitation in law of the sea (customary international law and court decisions)

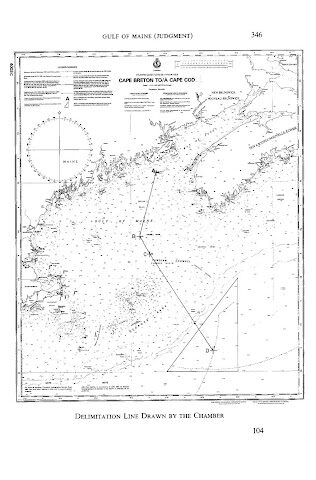

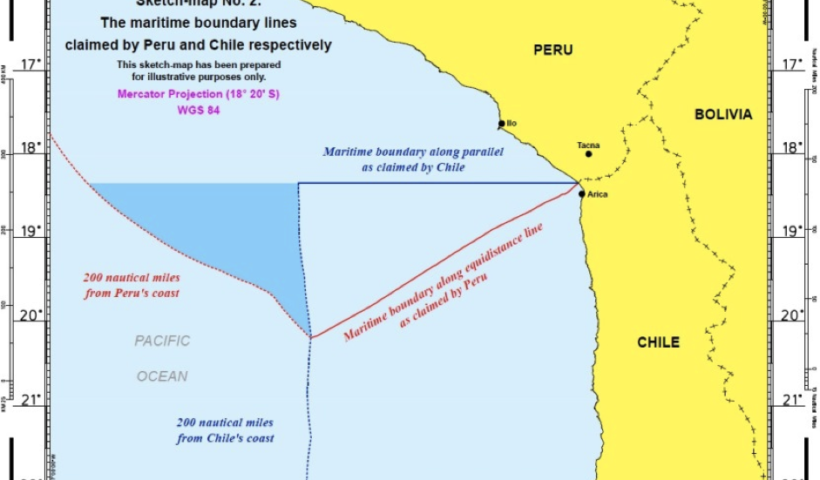

Three-stage Approach of Maritime Delimitation that the International Court of Justice (ICJ) “has developed a settled jurisprudence relating to the interpretation of those provisions”, while quoting the Court’s description of the three-stage approach of first drawing a provisional delimitation line, then assessing that line in the light of the relevant circumstances of the case and finally applying the disproportionality test to determine whether the proposed boundary results in an equitable solution, which has been developed in the context of the delimitation of the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone. “international law thus calls for the application of an equidistance line, unless another line is required by special circumstances”. However, the assertion that the ICJ’s three-stage approach is settled jurisprudence in relation to article 15 is not borne out by a reading of the judgments. The quotation in paragraph 999 of the Award is from the judgment of the Court in Peru v. Chile. As the Award indicates, the Court in this connection makes reference to its earlier decisions in Black Sea and Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia). All three decisions discuss the three-stage approach in relation to the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf and there is nothing in these judgments suggesting that the Court considered that the three-stage approach applies equally to the delimitation of the territorial sea under article 15 of the Convention.

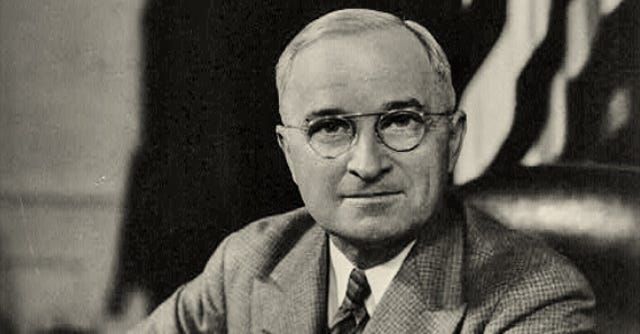

View More Three-stage Approach of Maritime Delimitation in law of the sea (customary international law and court decisions)The Truman Proclamation, 1945 (Proclamation 2667—Policy of the United States With Respect to the Natural Resources of the Subsoil and Sea Bed of the Continental Shelf)

U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s executive order on September 28, 1945, proclaiming that the resources on the continental shelf contiguous to the United States belonged to the United States. This was a radical departure from the existing approach, under which the two basic principles of the law of the sea had been a narrow strip of coastal waters under the exclusive sovereignty of the coastal state and an unregulated area beyond that known as the high seas. The speed at which Truman’s continental shelf concept was recognized through emulation or acquiescence led Sir Hersch Lauterpacht to declare in 1950 that it represented virtually “instant custom.”

View More The Truman Proclamation, 1945 (Proclamation 2667—Policy of the United States With Respect to the Natural Resources of the Subsoil and Sea Bed of the Continental Shelf)what is the meaning of Special Circumstances and Relevant Circumstances in delimitation process at law of the sea

Special circumstances are those circumstances which might modify the results produced by an unqualified application of the equidistance principles. Small islands and maritime features are arguably the archetypical special circumstances as much in the delimitation of the territorial sea as in the delimitation of the continental shelf/EEZ. The Court has recognized in numerous cases, including the North Sea Continental Shelf, Tunisia/Libya, Libya/Malta and Qatar v. Bahrain cases that the equitableness of an equidistance line depends on whether the precaution is taken of eliminating the disproportionate effect of certain islets, rocks and minor coastal projections.

View More what is the meaning of Special Circumstances and Relevant Circumstances in delimitation process at law of the seaequitable result in maritime delimitation and most acceptable law for delimitation process

The notion of equity is at the heart of the delimitation of the CS(continental shelf) and entered into the delimitation process with the 1945 proclamation of US President Truman, concerning the delimitation of the CS between the Unites States and adjacent States. The Truman proclamation inspired the Court during the 1969 North Sea case, when the Court stated that “delimitation is to be effected by agreement in accordance with equitable principles, and taking into account all the relevant circumstances.” This idea became doctrine and was reiterated and confirmed by the ICJ and arbitral tribunals in subsequent cases. Articles 74 and 83 of the 1982 LOS Convention concerning the delimitation of the EEZ and the CS provides for effecting the delimitation by agreement, in accordance with international law and in order to achieve an equitable result.

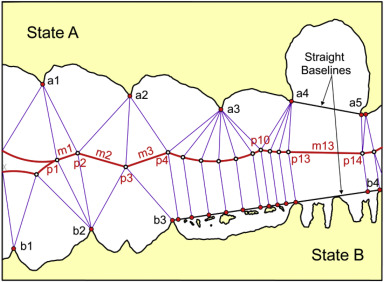

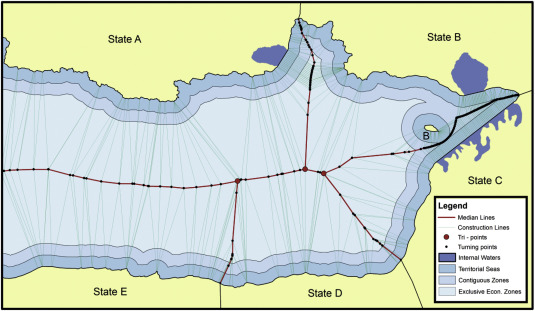

View More equitable result in maritime delimitation and most acceptable law for delimitation processDelimitation of the Maritime Boundaries between the adjacent States

Delimitation of the Maritime Boundaries between the adjacent Boundaries between the adjacent States , a PDF+PPT lecture by Nugzar Dundua, United Nations United Nations, The…

View More Delimitation of the Maritime Boundaries between the adjacent StatesOverlapping claims to territorial sea in law of the sea and LOSC

Delimitation of the territorial sea between States with opposite or adjacent coasts

Where the coasts of two States are opposite or adjacent to each other, neither of the two States is entitled, failing agreement between them to the contrary, to extend its territorial sea beyond the median line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points on the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial seas of each of the two States is measured. The above provision does not apply, however, where it is necessary by reason of historic title or other special circumstances to delimit the territorial seas of the two States in a way which is at variance therewith.

This provision in a near-verbatim reproduction of the equivalent provision of the 1958 Territorial Sea Convention. It reflects a compromise reached at UNCLOS I – and again at UNCLOS III – between two general proposed methods of delimitation.

Overlapping claims to internal waters in law of the sea and LOSC

Several adjacent coastal States have designated straight territorial sea baselines in a manner that generates overlapping claims to internal waters. The LOSC contains only limited references to internal waters, none of which concern delimitation or OCA management. The absence of detailed provisions in this context flows from the characterization of internal waters under customary law: Such waters appertain to the land territory of a coastal State and are subject, with limited exception, to full territorial sovereignty. The absence in the law of the sea of detailed rules concerning internal waters is a deliberate deference to the territorial rights of coastal States.

View More Overlapping claims to internal waters in law of the sea and LOSCMare Liberum

Mare Liberum (or The Freedom of the Seas) is a book in Latin on international law written by the Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, first published in 1609. In The Free Sea, Grotius formulated the new principle that the sea was international territory and all nations were free to use it for seafaring trade. The disputation was directed towards the Portuguese Mare clausum policy and their claim of monopoly on the East Indian Trade. Grotius wrote the treatise while being a counsel to the Dutch East India Company over the seizing of the Santa Catarina Portuguese carrack issue. The work was assigned to Grotius by the Zeeland Chamber of the Dutch East India Company in 1608.

View More Mare LiberumUnited Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and its implementing agreements in sustainable development

On 3 February 2014, on the margins of the eighth session of the Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals, the Division for Ocean Affairs…

View More United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and its implementing agreements in sustainable developmentThe UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, A HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

By the mid-1950s, it had become increasingly clear that existing international principles governing ocean

affairs were no longer capable of effectively guiding conduct on and use of the seas. The oceans had long been

subject to the freedom-of-the-sea doctrine — a seventeenth century principle that limited national rights and

jurisdiction over the oceans to a narrow belt of sea surrounding a nation’s coastline. The remainder of the seas

was proclaimed to be free to all and belonging to none.

But technological innovations, coupled with a global population explosion, had drastically changed man’s

relationship to the oceans. Larger and more advanced fishing fleets were endangering the sustainability of fish

stocks, the marine environment was increasingly threatened by pollution caused by industrial and other human

activity, and tensions between States over conflicting claims to the oceans and its vast resources were intensifying.

In this atmosphere, the United Nations convened the first of three conferences on the Law of the Sea in

Geneva in 1958. The conference produced four conventions, dealing respectively with the territorial sea and

the contiguous zone, the high seas, fishing and conservation of the living resources of the high seas, and the

continental shelf.

Two years later, the United Nations convened the Second Conference on the Law of the Sea, which, in spite

of intensive efforts, failed to produce an agreement on the breadth of the territorial sea and on fishing zones.

While the first two Conferences on the Law of the Sea had advanced a number of issues concerning international ocean affairs, the majority still remained unsolved. The creation of a comprehensive international

treaty was to become the legacy of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea.

A speech to the United Nations General Assembly by Malta’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Arvid

Pardo, on 1 November 1967, has often been credited with setting in motion a process that spanned 15 years and

culminated with the adoption of the Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1982. In his speech, Ambassador

Pardo urged the international community to take immediate action to prevent the breakdown of law and order

on the oceans, a disaster that many feared loomed on the horizon. He called for “an effective international

regime over the seabed and the ocean floor beyond a clearly defined national jurisdiction”.

Ambassador Pardo’s call to action came at the right time. In the next five years, the international community took several major steps that were crucial in setting the stage for a comprehensive treaty. In 1968, the

General Assembly established a Committee on the Peaceful Uses of the Seabed and the Ocean Floor beyond the

Limits of National Jurisdiction, which began work on a statement of legal principles to govern the uses of the

seabed and its resources. In 1970, the Assembly unanimously adopted the Committee’s Declaration of

Principles, which declared the seabed and ocean floor beyond the limits of national jurisdiction to be the common heritage of mankind. The same year, the Assembly decided to convene the Third Conference on the Law

of the Sea to create a single comprehensive international treaty that would govern all ocean affairs.

Third Conference on the Law of the Sea

The Third Conference on the Law of the Sea opened in 1973 with a brief organizational session, followed in 1974

by a second session held in Caracas, Venezuela. In Caracas, delegates announced that they would approach the

new treaty as a “package deal”, to be accepted as a whole in all its parts without reservation on any aspect. This

decision proved to be instrumental to the successful conclusion of the treaty.

A first draft was submitted to delegates in 1975. Over the next seven years, the text underwent several

major revisions. But on 30 April 1982, an agreement had been reached and the final text of the new convention

was put to a vote. The vote, which took place at United Nations Headquarters in New York, marked the end of over a

decade of intense and often strenuous negotiations, involving the participation of more than 160 countries from all

regions of the world and all legal and political systems.

The Convention was adopted with 130 States voting in favour, 4 against and 17 abstaining. Later that same year,

on 10 December, the Convention was opened for signature at Montego Bay, Jamaica, and received a record number of

signatures — 119 — on the first day.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea entered into force on 16 November 1994, one year after it

had reached the 60 ratifications necessary. Today the Convention is fast approaching universal participation, with 138

States, including the European Union, having become parties.

The Convention is supplemented by two agreements dealing respectively with Seabed Mining and Straddling and

Highly Migratory Fish Stocks.

Crimes at Sea, PIRACY AND SMUGGLING ON THE RISE

On the world’s oceans, piracy and armed robbery are on the rise. So is smuggling — especially of migrants

and drugs. Among the most widespread and serious at sea, these crimes are often masterminded by organized

criminals who take full advantage of weaknesses in law enforcement on the oceans. In some areas, they have

succeeded in undermining marine transport.

Maritime security and the safety of life at sea are also threatened by other criminal activities, such as terrorism, hijackings, the smuggling of arms and hazardous wastes, illegal fishing and dumping, the illegal discharge

of pollutants, and other violations of environmental laws.

Regime of the islands in law of the sea

Article 121 of the 1982 Convention deals with the regime of islands.

An island is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.

Except as provided for in paragraph 3, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf of an island are determined in accordance with the provisions of this Convention applicable to other land territory.

Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

difference between islands and rocks in law of the sea

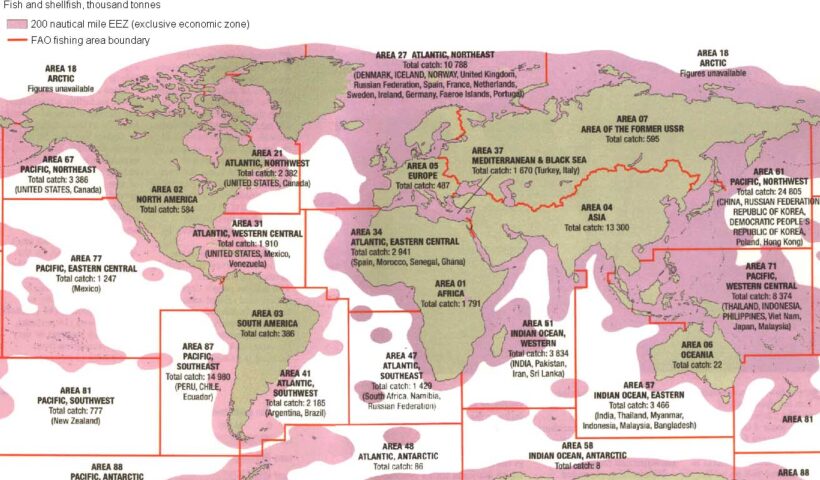

The definition and treatment of islands in maritime boundary delimitation are complex and important. This is because the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which came into effect in 1994, provides that islands, along with mainland coasts, may generate a full suite of maritime zones – including a 200 nm exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf claim as well as a 12 nm territorial sea. Thus, if no maritime neighbours were within 400 nm of the feature, an island has the potential to generate 125,664 sq. nm [431,014 km2] of territorial sea, EEZ and continental shelf rights. There is also the consideration that oceans remain an important source of living resources, with fisheries representing a major industry for many coastal states.

View More difference between islands and rocks in law of the seaThe Right to Seek Asylum in law of the sea

The 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, defines a refugee as a person who:“owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his [or her] nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself [or herself ] of the protection of that country”. (Article 1A(2)) It further prohibits that refugees or asylum-seekers “… be expelled or returned in any way “to the frontiers of territories where his [or her] life or freedom would be threatened on account of his [or her] race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” (Article 33 (1)). The scope of the principle of non-refoulement has a larger scope in the field of Human Rights Law. Indeed, it protects every person and not only the refugees and asylum seeker and the scope of its protection is larger. Human Rights prohibits every expulsion or refoulement to a country where the person is at risk of suffering torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, sometimes the execution of the death penalty and sometimes a grave denial of justice.

View More The Right to Seek Asylum in law of the seaThe obligation to rescue people in distress at sea

Rescue of people in distress at sea, regardless of their nationality or status, is an unconditional obligation for all ships in vicinity and coastal state authorities. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS Convention) provides that:

“ Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag, in so far as he can do so without serious danger to the ship, the crew or the passengers: (a) to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost; (b) to proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distress, if informed of their need of assistance, in so far as such action may reasonably be expected of him.” (Art. 98 (1))

Migrants’ rights at sea

The main rights and obligations concerning migrants attempting to cross the sea clandestinely are framed by the following legal norms: The right to leave any country, including his own and its limits

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that:

“Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country” (Article 13. (2)). Article 5 of the 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination provides that state parties undertake to prohibit and to eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms and to guarantee the right of everyone, without distinction as to race, colour, or national or ethnic origin, to equality before the law, notably in the enjoyment of [c, ii)] the right to leave any country, including one’s own, and to return to one’s country.”

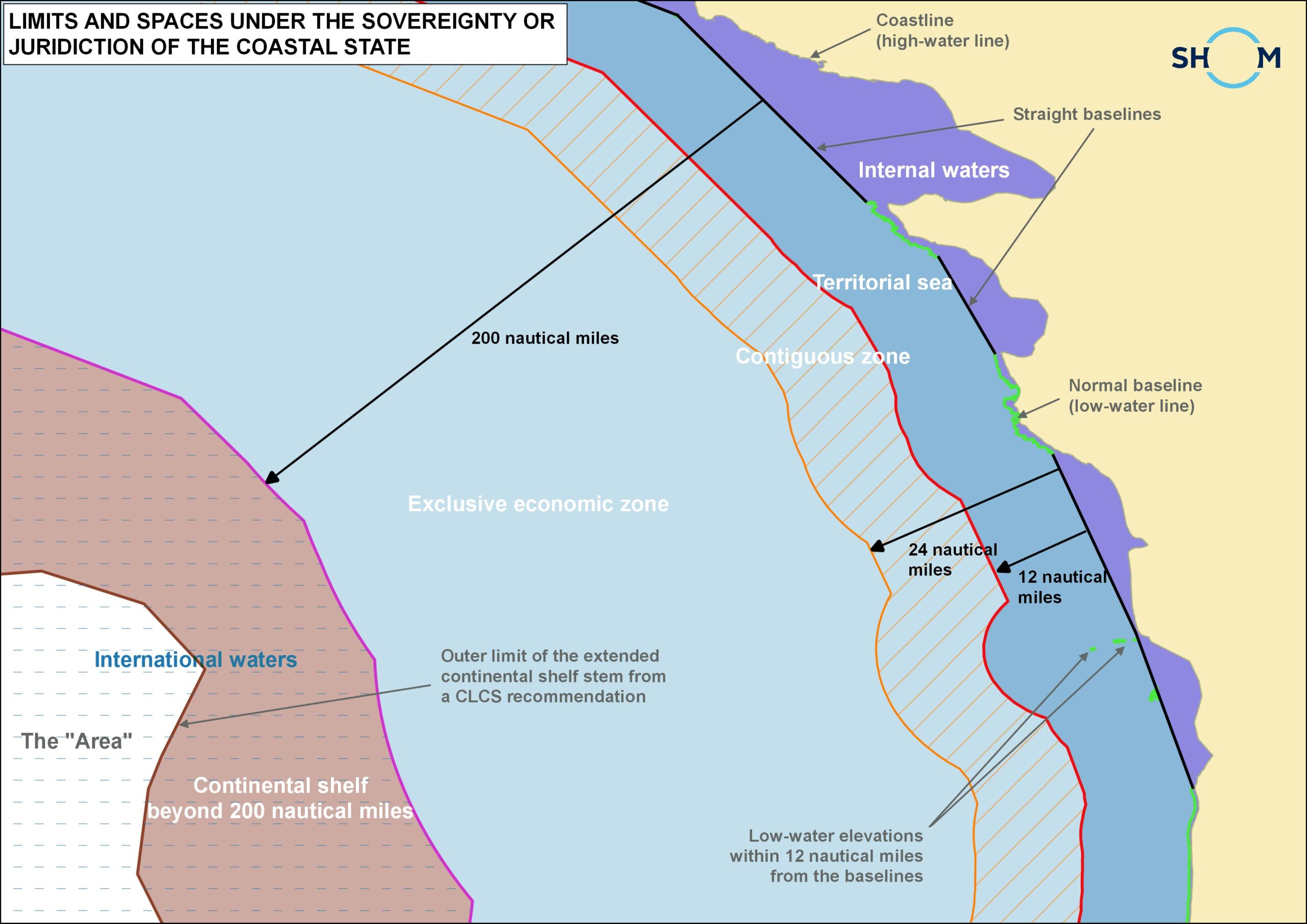

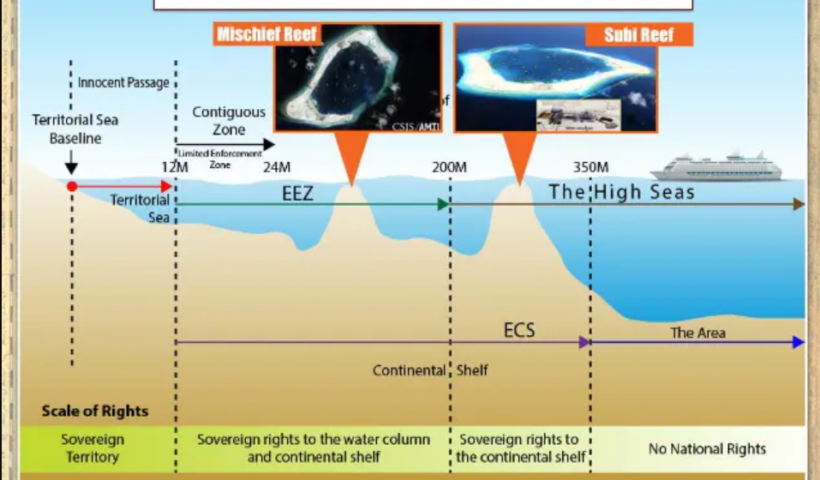

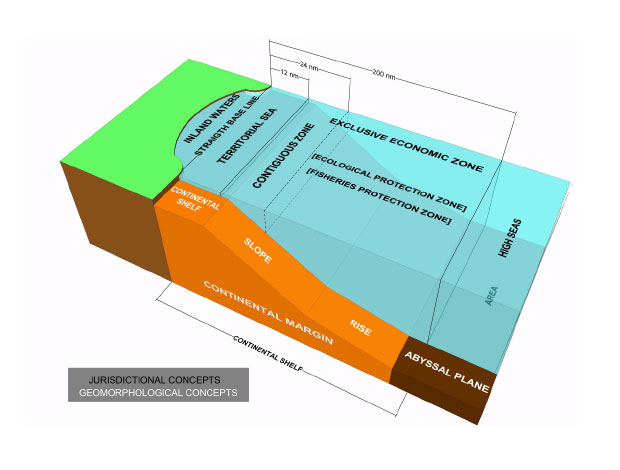

RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES IN MARITIME ZONES

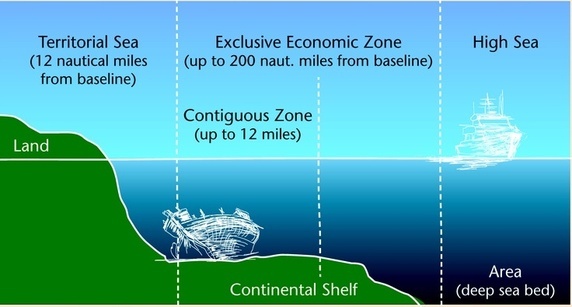

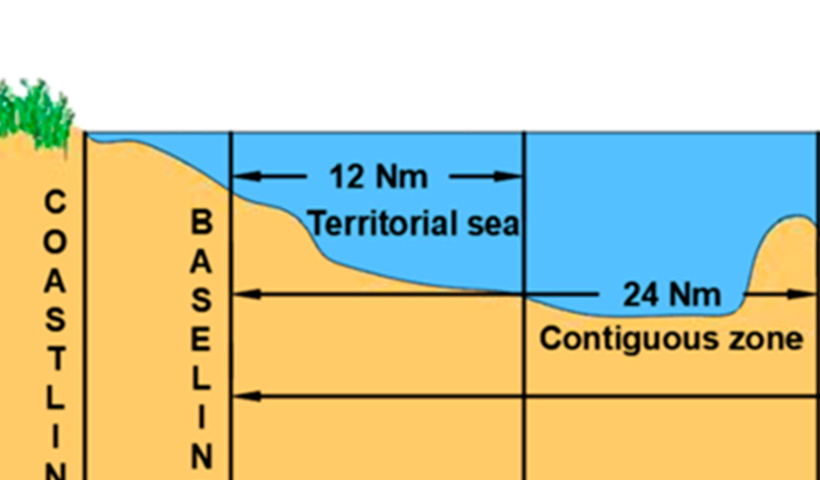

Coastal states can claim five key maritime zones. Proceeding seawards from the coast they are internal waters, territorial seas, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone (or, in some cases, an exclusive fishing zone) and the continental shelf. Archipelagic states may also claim archipelagic waters within their archipelagic baselines. Beyond these national zones of jurisdiction lie the international maritime zones of the high seas and the Area.

The rights of the coastal state and aliens vary in these maritime zones, and do so both spatially and functionally. Thus, the coastal state has more rights closer to shore, for example in internal waters and the territorial sea. Aliens retain considerable rights within a coastal state’s claimed maritime zones concerned with communication issues such as navigation, overflight and the laying of submarine cables and pipelines. The coastal state, in contrast, boasts significant resource related rights, particularly concerning fishing and mineral extraction from the seabed.

Exclusive Fishery Zones meaning and which countries have it?

where no EEZ claim has been made, several states instead claim an exclusive fishery zone. A significant proportion of these states border the Mediterranean Sea which has witnessed a dearth of EEZ claims.

The Mediterranean littoral states are not opposed to the EEZ concept in principle, but have been dissuaded from making EEZ claims because of ‘a twofold economico-geographic reason’. The geographical part of this reason relates to the fact that the physical dimensions of the Mediterranean preclude any coastal state from claiming an EEZ out to 200 nm from its baselines. The economic dimension refers to the the relatively unproductive nature of the Mediterranean from a fisheries perspective. Fishery zones have also been claimed by several states on behalf of their dependent territories.

what is the deference between national and international maritime zones?

The rights coastal states have in certain maritime zones, notably internal waters, the territorial sea and contiguous zone, affords them security in the face of threats such as smuggling, illegal immigration, other forms of cross-border crime and, ultimately, from the threat of terrorism and the use of military force. The national maritime zones outlined in the UN Convention also offer profound benefits to coastal states in respect of resources, both living resources such as fisheries and non-living resources such as oil and gas. Furthermore, the rights and responsibilities relating to national maritime zones as laid down in the 1982 Convention provide coastal states with opportunities and obligations in the sphere of ocean management. This includes, but is not limited to, navigation, fisheries protection, conservation of living resources, pollution control, search and rescue and marine scientific research.

View More what is the deference between national and international maritime zones?INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION FOR THE SAFETY OF LIFE AT SEA, 1974

The main objective of the SOLAS Convention is to specify minimum standards for the construction, equipment and operation of ships, compatible with their safety. Flag States are responsible for ensuring that ships under their flag comply with its requirements, and a number of certificates are prescribed in the Convention as proof that this has been done. Control provisions also allow Contracting Governments to inspect ships of other Contracting States if there are clear grounds for believing that the ship and its equipment do not substantially comply with the requirements of the Convention – this procedure is known as port State control. The current SOLAS Convention includes Articles setting out general obligations, amendment procedure and so on, followed by an Annex divided into 14 Chapters.

View More INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION FOR THE SAFETY OF LIFE AT SEA, 1974Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Torres Strait case study

The Torres Strait has been defined as the area of water between Cape York Peninsula in Australia’s extreme north coastline and the islands of New Guinea. It is bounded in the west by the Arafura Sea and in the east by the Great Barrier Reef and the Coral Sea. The strait is about 81 miles (150 km) wide and almost 108 miles (200 km) long between the islands at its eastern and western ends. The strait is, however, shallow and contains reefs and many small islands.

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Torres Strait case studyConvention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone(TSC)

Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone Geneva, 29 April 1958 had Entry into force in 10 September 1964, in accordance with article 29. its Registration on the UN is 22 November 1964, No. 7477. till no it had 41 and 52 Parties.

View More Convention on the Territorial Sea and the Contiguous Zone(TSC)The summary of UNCLOS in short(table+pdf+jpg)

United Nations Convention on the Law of the sea (UNCLOS) was Adopted in 10 December 1982 Enforced since 16 November 1994 Amended twice – in 1994, “Agreement relating to the Implementation of Part XI of the Convention”, in force in 1996. 17 Parts, 320 Articles and 9 Annexes As of Nov. 2004, there are 146 ratifications. UNCLOS Has 320 articles and 9 annexes governing all aspects of ocean space- delimitation, environmental control, marine scientific research, economic and commercial activities, transfer of technology and the settlement of disputes relating to ocean matters.

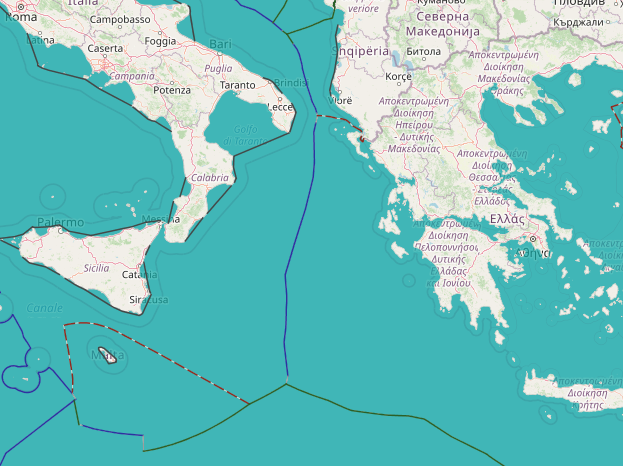

View More The summary of UNCLOS in short(table+pdf+jpg)maritime boundaries between Italy and Greece

maritime boundaries between Italy and Greece, Greece, Greece EEZ map, Greece exclusive economic zone, Greece maritime boundaries, Greece maritime claims, italy, Italy and greece maritime delimitation, Italy continental shelf map, Italy exclusive economic zone map, Italy marine zone, Italy maritime boundaries, Italy maritime claims, Italy territorial waters map

View More maritime boundaries between Italy and GreeceNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, United Kingdom Straits(Dover Strait, North Channel, Fair Isle Gap) case study

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, United Kingdom Straits(Dover Strait, North Channel, Fair Isle Gap) case study, How far is it from Northern Ireland to Scotland?, How wide is the North Channel?, What is the strait between England and France?, What two bodies of water does the Strait of Dover connect?, Where is the North Channel?, Which is the busiest strait in the world?, Why is the Strait of Dover important?

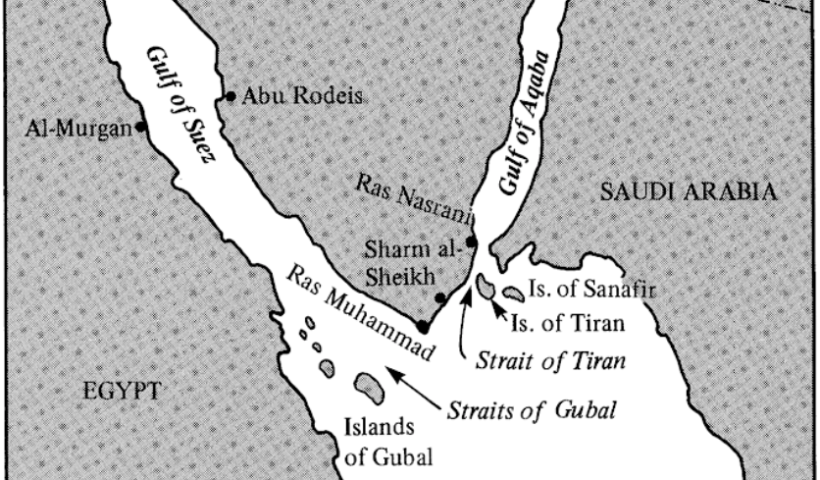

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, United Kingdom Straits(Dover Strait, North Channel, Fair Isle Gap) case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Tiran case study

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Tiran case study, 1979 Treaty of Peace between Egypt and Israel, Gulf of Aqaba, Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Strait of Tiran, the Gulf of Aqaba, The Strait of Tiran, The strategic importance of the strait of Tiran, What is the body of water between the Red Sea and the Arabian Sea?, What is the importance of the Straits of Tiran?, What is the meaning of strait?, What separates Saudi Arabia from Egypt and Israel?, Who owns Tiran Island?

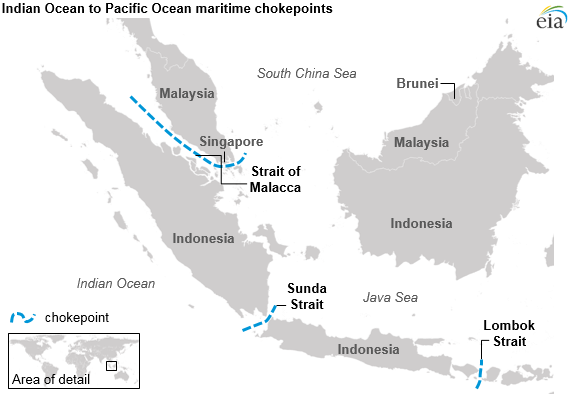

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Tiran case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Sunda and Lombok case study

Sunda Strait, located between the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Java, provides the major sea link between the Indian Ocean and the Java Sea and into East Asian waters. (See Map 25 above.) It is approximately 50 miles long, and at its narrowest point is 13.8 miles wide. Sangian Island separates the 2.4-milewide western channel and the 3.7-mile-wide eastern channel. Sunda’s governing depth is about 100 feet but is not considered suitable for submerged passage given the hydrographic characteristics of its northern exit and the extent of its commercial use.. Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Sunda and Lombok case study, How deep is the Lombok Strait?, How did Sunda Strait tsunami happen?, How many straits are there in the world?, Lombok Strait, Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Sunda and Lombok, Sunda Strait, The Indo-Pacific’s maritime choke points, What is the meaning of strait?, Where is Sunda Strait?, Which strait connects Java Sea to Indian Ocean?

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Sunda and Lombok case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Baltic Straits(The Oresund and the Belts) case study

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Baltic Straits(The Oresund and the Belts) case study, Baltic Straits, Danish straits, Danish Straits maritime chokepoints, Great Belt, Little Belt, Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Sound (Oresund), The Oresund and the Belts, What is the strait between Denmark and Sweden?, What separates the North Sea from the Baltic Sea?, What strait is between Denmark and Norway?, Where is the Baltic Strait?, Where is the Kattegat Strait?

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Baltic Straits(The Oresund and the Belts) case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Northwest Passage case study

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Northwest Passage case study, Baffin Bay, Beaufort Sea, Can you sail through the Northwest Passage?, Davis Strait, Northwest Passage, What body of water opens to the Davis Strait?, What is the Northwest Passage and why is it important?, What separates Greenland from Canada?, What was the Northwest Passage and why were explorers looking for it?, Where is the Davis Strait located?, Which named line of latitude crosses the Davis Strait?

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Northwest Passage case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Northeast Passage (Barents Sea and the Chukchi Sea)case study

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Northeast Passage (Barents Sea and the Chukchi Sea)case study, Barents Sea, Can you sail through the Northwest Passage?, Chukchi Sea, Did the Infinity make the Northwest Passage?, Is there a North West Passage?, Kara Sea, Laptev Strait, Northeast Passage, NORTHERN SEA ROUTE, Sannikov Strait, What are the Northeast and Northwest Passages?, What is the Northwest Passage and why is it important?, Who discovered the Northeast Passage?

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Northeast Passage (Barents Sea and the Chukchi Sea)case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Messina case study

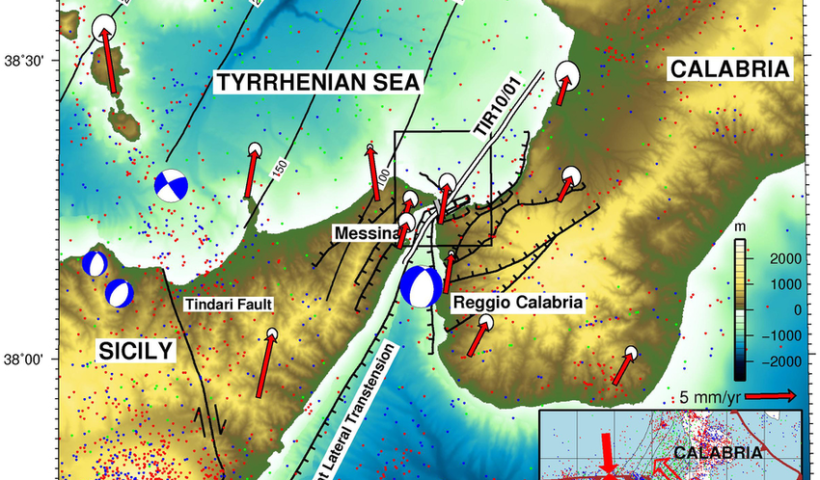

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Messina case study, italy, non-suspendable innocent passage, Sicily, Strait of Messina, What is the name of the strait between Italy and Sicily?

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Messina case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Malacca and Singapore case study

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Malacca and Singapore case study, Indonesia, malaysia, Singapore Strait, south china sea, Straits of Malacca, What does the Strait of Malacca connect?, Where is Malacca Strait?, Which is the busiest strait in the world?, Who controls Malacca Strait?

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Malacca and Singapore case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Magellan case study

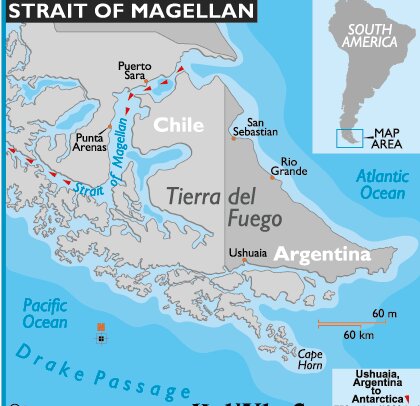

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Magellan case study, 1881 Boundary Treaty between Argentina and Chile, 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship between Argentina and Chile, 5 Strait of Magellan Facts You Must Know, Is the Strait of Magellan still used?, Magellan Strait, strait of magellan facts, What does the Strait of Magellan separates?, What two bodies of water does the Strait of Magellan connect?, What’s the bottom of South America called?, Where are the Straits of Magellan?, why is the strait of magellan important

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Magellan case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Kuril Straits case study

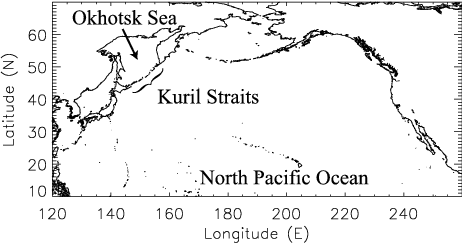

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Kuril Straits case study, Adjacent waters of Etorofu Is, Can you visit the Kuril Islands?, Does Japan own the Kuril Islands?, Etorofu Strait, Golovnina Strait, Iturup, Kuril islands, Kuril Islands dispute, Kuril Straits On a Map, Vries Strait, What country owns the Kuril Islands?

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Kuril Straits case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Hormuz case study

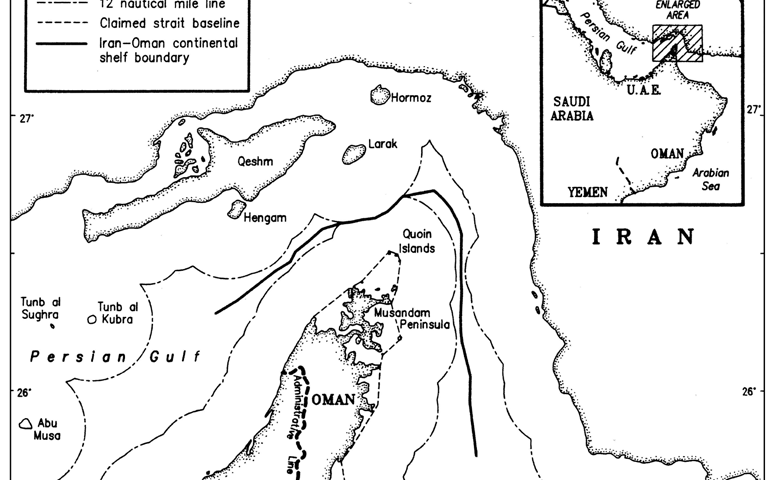

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Hormuz case study, Are the Straits of Hormuz international waters?, Does Iran own the Strait of Hormuz?, Is the Strait of Hormuz dangerous?, Strait of Hormuz, Strait of Hormuz – Geography, strait of hormuz map, the world’s biggest oil chokepoint, Which country controls the Strait of Hormuz?, Why is the Strait of Hormuz a choke point?, Why Strait of Hormuz is important?, Why the Strait of Hormuz Matters to Iran and the World

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Hormuz case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Gibraltar case study

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Gibraltar case study, atlantic ocean, current gibraltar strait, gibraltar strait map, gibraltar strait separates, How deep is the water at the Strait of Gibraltar?, Is the Strait of Gibraltar dangerous?, Strait of Gibraltar, Strait of Gibraltar – Origin and significance, Strait of Gibraltar crossing, strait of gibraltar is controlled by, strait of gibraltar upsc, Traffic Separation Scheme area, What country owns the Strait of Gibraltar?, What separates Spain from Africa?, Who owns Gibraltar?, Why is the Strait of Gibraltar so important?

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Gibraltar case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Bosporus and Dardanelles case study

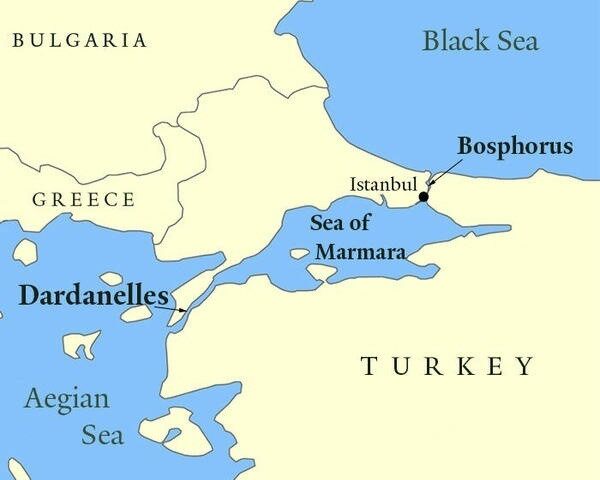

These straits, also known as the Turkish Straits or the Black Sea Straits, connect the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea via the Sea of Marmara. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara, while the Dardanelles connects the Aegean Sea with the Sea of Marmara. The Bosporus is about 17 miles long and varies in width between one-third and 2 miles. The Dardanelles is about 35 miles long, its width decreases from 4 miles at the Aegean to about 0.7 miles at its narrowest; its depth varies from 160 to 320 feet. The Sea of Marmara is about 140 miles long. Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Bosporus and Dardanelles case study, A map showing the Straits, Aegean sea, Black Sea Straits, Bosporus and Dardanelles, How deep is the Bosporus Dardanelles channel?, Montreux Convention, Sea of Marmara, The Dardanelles and Bosporus Passages, Turkish Straits, Who controls Black Sea?, Why are the Bosporus and Dardanelles important?, Why are the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits significant

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Bosporus and Dardanelles case studyNavigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Bonifacio case study

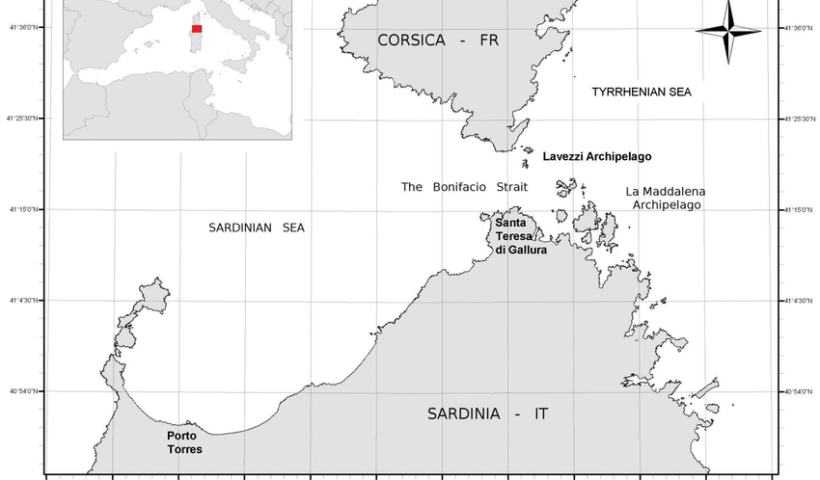

Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Bonifacio case study, Bonifacio case study, French island of Corsica, Italian island of Sardinia, Messina Strait, navigation in the Strait of Bonifacio, Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Particular Straits, Particularly Sensitive Sea Area, ResearchGate The Bonifacio Strait area, transit of the Strait of Bonifacio

View More Navigational Regimes of Particular Straits, Bonifacio case study