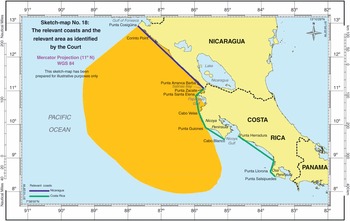

It is beyond serious argument that geographical factors play an important role in maritime delimitation. In fact, every international judgment regarding maritime delimitation has taken them into account. Three factors merit highlighting in particular.

The first factor concerns the distinction between opposite and adjacent coasts. International courts and tribunals have attached great importance to the distinction when evaluating the appropriateness of the equidistance method. A reason for this distinction may be that the risks of inequity arising from the equidistance method are different between opposite and adjacent coasts. Nonetheless, currently international courts and tribunals tend to apply the equidistance method at the first stage of maritime delimitation, regardless of the configuration of the coast. Hence, it appears that the distinction between opposite and adjacent coasts is of limited value in the law of maritime delimitation.

Second, it has been considered that the concavity or convexity of coasts constitutes a relevant circumstance. In particular, the ICJ, in the North Sea Continental Shelf cases, regarded the equidistance method as inequitable where coasts are concave on account of the distorting effect produced by that method. This view was echoed by the Libya/Malta judgment. ITLOS, in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case, observed that Bangladesh’s coast, seen as a whole, is ‘manifestly concave’ and that the provisional equidistance line produces a cut-off effect on the maritime projection of Bangladesh. It thus ruled that the concavity of the coast of Bangladesh was a relevant circumstance which required an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line. Similarly, in the Bangladesh/India Arbitration, the concavity of the Bay of Bengal was considered as a relevant circumstance which required an adjustment of the provisional equidistance line. In reality, however, it is often difficult to define concavity and convexity of the coast in practice. The difficulty was highlighted in the following paragraph of the Guinea/Guinea-Bissau award:

If the coasts of each country are examined separately, it can be seen that the Guinea-Bissau coastline is convex, when the Bijagos are taken into account, and that that of Guinea is concave. However, if they are considered together, it can be seen that the coastline of both countries is concave and this characteristic is accentuated if we consider the presence of Sierra Leone further south.

In fact, interpretation of the configuration of the coast may vary according to the scale of the map or micro- or macro geography, i.e. the question of whether coasts of third neighboring States will be taken into account in appreciating the configuration of the coasts concerned.

The third factor is the general direction of the coast. While the determination of the general direction of the coast was at issue in the Tunisia/Libya and Gulf of Maine cases, the most dramatic impact of the general direction of the coast can be seen in the Guinea/Guinea-Bissau case. In that case, the Arbitral Tribunal drew a line grosso modo perpendicular to the general direction of the coastline joining Pointe des Almadies (Senegal) and Cape Schilling (Sierra Leone), arguing that the overall configuration of the West African coastline should be taken into account. The point to be noted is that, when specifying the general direction of the coast, the Arbitral Tribunal selected two points located in third States.

Nonetheless, with respect, the selection of the Tribunal is open to question. In fact, the line connecting Pointe des Almadies and Cape Schilling cuts almost all of the coast of Guinea Bissau for nearly 350 kilometers and runs approximately 70 kilometers inside the latter’s territory. As a consequence, the line selected by the Tribunal is clearly unfavourable to Guinea-Bissau and entails the risk of refashioning nature.