The delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles is a comparatively new subject in the law of maritime delimitation. In this regard, three issues need further consideration: (i) entitlements to the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles, (ii) the relationship between the CLCS and an international court or tribunal, and (iii) the methodology.

(a) Entitlements

Above all other aspects, an international court or tribunal must examine whether the Parties have overlapping entitlements to the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

In the Bangladesh/Myanmar, Bangladesh/India and Ghana/Côte d’Ivoire cases, international tribunals accepted that the Parties had entitlements to the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles on the basis of the existence of agreement between the Parties and/or submissions of information to the CLCS. However, the particular circumstances as shown

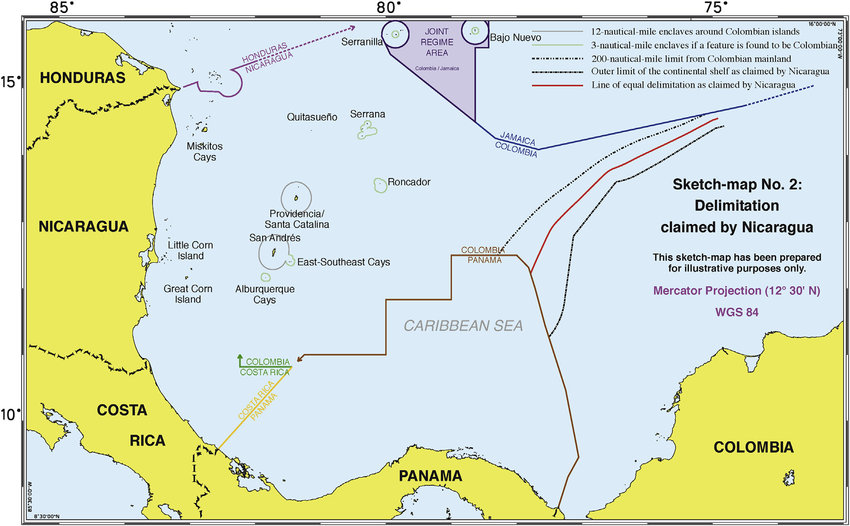

by the unique nature of the Bay of Bengal will not exist in other regions. Furthermore, there is no guarantee that the Parties in dispute will always agree on the existence of entitlements to the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles. Where no agreement exists in this matter, an international court or tribunal may encounter difficulties. In the Nicaragua/Colombia case, for instance, Colombia claimed that there are no areas of extended continental shelf within this part of the Caribbean Sea. The ICJ, in its judgment of 2012, refrained from delimitation of the continental shelf boundary beyond 200 nautical miles on the grounds that Nicaragua had not established that it has a continental margin that extends far enough to overlap with Colombia’s 200-nautical-mile entitlement to the continental shelf, measured from Colombia’s mainland coast. In 2013, however, Nicaragua instituted new proceedings against Colombia with regard to the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles from the Nicaraguan coast. The Court, in its judgment of 2016 (Preliminary Objections), noted that Nicaragua provided the CLCS with the ‘final’ information required in Article 76(8) of the LOSC. The vote was tied, eight votes to eight, but by the President’s casting vote Nicaragua’s request was admitted, concerning the precise course of the maritime boundary between Nicaragua and Colombia in the areas of the continental shelf which appertain to each of them beyond the boundaries determined by the Court in its judgment of 19 November 2012.

(b) The Relationship Between the CLCS and an International Court or Tribunal

The next issue concerns the relationship between the CLCS and an international court or tribunal. In this regard, international tribunals emphasise the difference between delineation under Article 76 and delimitation under Article 83 of the LOSC. For instance, ITLOS in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case ruled:

There is a clear distinction between the delimitation of the continental shelf under article 83 and the delineation of its outer limits under article 76. Under the latter article, the Commission is assigned the function of making recommendations to coastal States on matters relating to the establishment of the outer limits of the continental shelf, but it does so without prejudice to delimitation of maritime boundaries. The function of settling disputes with respect to delimitation of maritime boundaries is entrusted to dispute settlement procedures under article 83 and Part XV of the Convention, which include international courts and tribunals.

For the Tribunal, ‘the exercise of its jurisdiction in the present case cannot be seen as an encroachment on the functions of the Commission’. ITLOS thus concluded that in order to fulfil its responsibilities under Part XV, section 2 of the Convention, it had an obligation to delimit the continental shelf between the Parties beyond 200 nautical miles. The dictum of ITLOS was echoed by the Annex VII Arbitral Tribunal in the Bangladesh/India case and the ITLOS Special Chamber in the Ghana/Côte d’Ivoire case.

The difference between the delineation of the outer limits of the continental shelf and maritime delimitation was also stressed by the ICJ in the Question of the Delimitation of the Continental Shelf between Nicaragua and Colombia beyond 200 nautical miles from the Nicaraguan Coast. The Court held:

[S]ince the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles can be undertaken independently of a recommendation from the CLCS, the latter is not a prerequisite that needs to be satisfied by a State party to UNCLOS before it can ask the Court to settle a dispute with another State over such a delimitation.

In Maritime Delimitation in the Indian Ocean (Preliminary Objections), however, the ICJ appeared to take a more nuanced view:

A lack of certainty regarding the outer limits of the continental shelf, and thus the precise location of the endpoint of a given boundary in the area beyond 200 nautical miles, does not, however, necessarily prevent either the States concerned or the Court from undertaking the delimitation of the boundary in appropriate circumstances before the CLCS has made its recommendations.

The term ‘in appropriate circumstances’ can be interpreted to mean that the Court would decide whether the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles should be effected before recommendations of the CLCS on a case-by-case basis. In this connection, ITLOS, in the Bangladesh/Myanmar case, admitted that it ‘would have been hesitant to proceed with the delimitation of the area beyond 200 nm had it concluded that there was significant uncertainty as to the existence of a continental margin in the area in question’.

(c) Methodology

The third issue relates to the methodology applicable to the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles. In this regard, ITLOS held that Article 83 of the LOSC applies equally to the delimitation of the continental shelf both within and beyond 200 nautical miles; and that the delimitation method to be employed in the present case

for the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles should not differ from that within 200 nautical miles. ITLOS’ approach was echoed by the Annex VII Arbitral Tribunal in the 2014 Bangladesh/India Arbitration.

The concept of ‘one single continental shelf’ provides a legal basis for the application of the same method to the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

This concept was presented by the Arbitral Tribunal in the Barbados/Trinidad and Tobago case, stating: ‘There is in law only a single “continental shelf” rather than an inner continental shelf and a separate extended or outer continental shelf.’ Subsequently the concept of ‘one single continental shelf’ was confirmed in the Bangladesh/Myanmar,

Bangladesh/India and Ghana/Côte d’Ivoire cases.186 In the words of the ITLOS Special Chamber in the Ghana/Côte d’Ivoire case:

As far as the methodology for delimiting the continental shelf beyond 200 nm is concerned, the Special Chamber recalls its position that there is only one single continental shelf. Therefore it is considered inappropriate to make a distinction between the continental shelf within and beyond 200 nm as far as the delimitation methodology is concerned.

According to the dictum, the same delimitation method, i.e. the three-stage approach, can equally apply to the delimitation of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles. In relation to the lateral delimitation, international courts and tribunals would encounter no serious difficulty in extending the delimitation line in the same direction until it reached the outer limits of the continental shelf. In fact, the Bangladesh/Myanmar, Bangladesh/India and Ghana/Côte d’Ivoire cases related to delimitation between States with adjacent coasts.

However, whether the same methodology can apply to the delimitation between States with opposite coasts needs further consideration.