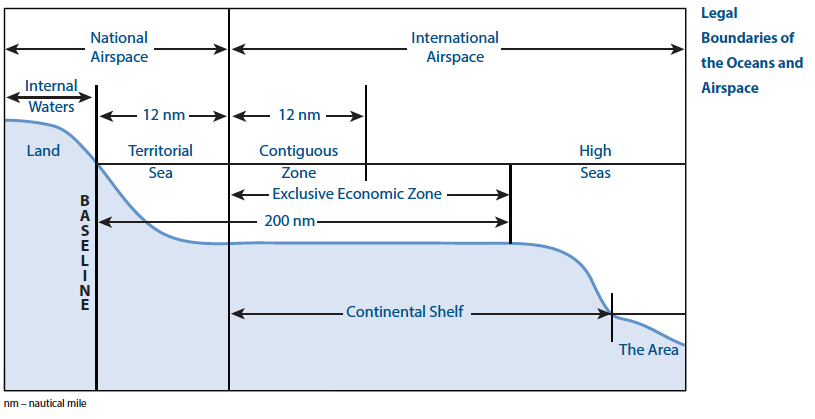

The landward limit of the EEZ is the seaward limit of the territorial sea. The seaward limit of the EEZ is at a maximum of 200 nautical miles from the baseline of the territorial sea. Given that the maximum breadth of the territorial sea is 12 nautical miles, the maximum breadth of the EEZ is 188 nautical miles, that is to say, approximately 370 kilometres. The outer limit lines of the EEZ and the delimitation lines shall be shown on charts of a scale or scales adequate for ascertaining their position. Where appropriate, lists of geographical coordinates of points may also be substituted for such outer limit lines or delimitation lines pursuant to Article 75(1) of the LOSC. The coastal State is also obliged to give due publicity to such charts or lists of geographical coordinates and shall deposit a copy of each such chart or list with the UN Secretary-General under Article 75(2).

The concept of the EEZ comprises the seabed and its subsoil, the waters superjacent to the seabed as well as the airspace above the waters. With respect to the seabed and its subsoil, Article 56(1) provides:

in the exclusive economic zone the coastal State has sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil.

It would follow that the concept of the EEZ includes the seabed and its subsoil. The rights of the coastal State with respect to the seabed and subsoil are to be exercised in accordance with provisions governing the continental shelf by virtue of Article 56(3).

Article 58(1) stipulates that ‘in the exclusive economic zone’, all States, whether coastal or land-locked, enjoy ‘the freedoms referred to in Article 87 of navigation and overflight’ (emphasis added). Article 56(1) further provides that the coastal State has sovereign rights with respect to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy from the water, currents and winds. One can say, therefore, that the concept of the EEZ also includes the airspace.

Article 55 of the LOSC makes clear that the EEZ ‘is an area beyond and adjacent to the territorial sea, subject to the specific legal regime established in this Part [V]’. Thus, the EEZ is not the territorial sea. Indeed, unlike internal waters and the territorial sea, the territorial sovereignty of the coastal State does not extend to the EEZ. Article 86 of the LOSC states that the provisions of Part VII governing the high seas ‘apply to all parts of the sea that are not included in the exclusive economic zone, in the territorial sea or in the internal waters of a State, or in the archipelagic waters of an archipelagic State’. Accordingly, the EEZ is not part of the high seas. In fact, the freedoms apply to the EEZ in so far as they are not incompatible with Part V of the LOSC governing the EEZ in accordance with Article 58(2).

In this sense, the quality of the freedom exercisable in the EEZ differs from that exercisable on the high seas. Overall it can be concluded that the EEZ is regarded as a sui generis zone, distinguished from the territorial sea and the high seas.

Sovereign Rights Over the EEZ

The key provision concerning coastal State jurisdiction over the EEZ is Article 56 of the LOSC. The first paragraph of Article 56 provides:

- In the exclusive economic zone, the coastal State has:

(a) sovereign rights for the purpose of exploring and exploiting, conserving and managing the natural resources, whether living or non-living, of the waters superjacent to the seabed and of the seabed and its subsoil, and with regard to other activities for the economic exploitation and exploration of the zone, such as the production of energy

from the water, currents and winds.

It is important to note that the sovereign rights of the coastal State over the EEZ are essentially limited to economic exploration and exploitation (limitation ratione materiae). In this respect, the concept of sovereign rights must be distinguished from territorial sovereignty, which is comprehensive unless international law provides otherwise.

The concept of sovereign rights can also be seen in the 1958 Geneva Convention on the Continental Shelf. Article 2(2) of the Geneva Convention provides:

The rights referred to in paragraph 1 of this Article [sovereign rights] are exclusive in the sense that if the coastal State does not explore the continental shelf or exploit its natural resources, no one may undertake these activities, or make a claim to the continental shelf, without the express consent of the coastal State.

Although Part V does not contain a similar provision, it may be argued that sovereign rights in the EEZ are essentially exclusive in the sense that no one may undertake these activities or make a claim to the EEZ, without the express consent of the coastal State. It is true that third States have the right of access to natural resources in the EEZ. Considering that the exercise of the right is conditional upon agreement with the coastal State, however, it does

not challenge the exclusive nature of the coastal State’s jurisdiction over the EEZ. With respect to matters provided by the law, the coastal State exercises both legislative and enforcement jurisdiction in the EEZ. In this respect, the key provision is Article 73(1):

The coastal State may, in the exercise of its sovereign rights to explore, exploit, conserve and manage the living resources in the exclusive economic zone, take such measures, including boarding, inspection, arrest and judicial proceedings, as may be necessary to ensure compliance with the laws and regulations adopted by it in conformity with this Convention.

While this provision provides enforcement jurisdiction for the coastal State, the reference to ‘the laws and regulations by it’ suggests that the State also has legislative jurisdiction. In fact, Article 62(4) prescribes specific contents of the laws and regulations of coastal States with regard to fishing of nationals of other States in the EEZ. Article 73(1) makes no reference to confiscation of vessels. However, ITLOS took the view that this provision may encompass confiscation of vessels in the EEZ.

It is beyond serious doubt that the measures provided under Article 73(1) can be applied to foreign vessels within the EEZ. This is clear from Article 73(4):

In cases of arrest or detention of foreign vessels the coastal State shall promptly notify the flag State, through appropriate channels, of the action taken and of any penalties subsequently imposed. Thus a coastal State jurisdiction within its EEZ contains no limit ratione personae. Overall the sovereign rights of the coastal State in its EEZ can be summarised as follows:

(i) The sovereign rights of the coastal State can be exercised solely within the EEZ. In this sense, such rights are spatial in nature.

(ii) The sovereign rights of the coastal State are limited to the matters defined by international law (limitation ratione materiae). On this point, sovereign rights must be distinguished from territorial sovereignty.

(iii) However, concerning matters defined by international law, the coastal State may exercise both legislative and enforcement jurisdiction.

(iv) The coastal State may exercise sovereign rights over all people regardless of their nationality within the EEZ. Thus sovereign rights contain no limit ratione personae. In this respect, sovereign rights over the EEZ differ from personal jurisdiction.

(v) The sovereign rights of the coastal State over the EEZ are exclusive in the sense that other States cannot engage upon activities in the EEZ without consent of the coastal State.

In short, unlike territorial sovereignty, the sovereign rights of the coastal State over the EEZ lack comprehensiveness of material scope. With respect to matters accepted by international law, however, the coastal State can exercise both legislative and enforcement jurisdiction over all people within the EEZ in an exclusive manner. The essential point is that the rights of the coastal State over the EEZ are spatial in the sense that they can be exercised solely within the particular space in question regardless of the nationality of persons or vessels. Thus the coastal State jurisdiction over the EEZ can be regarded as a spatial jurisdiction. Due to the lack of comprehensiveness of material scope, this jurisdiction should be called a limited spatial jurisdiction.

Due to its numerous overseas departments and territories scattered on all oceans of the planet, France possesses the largest EEZ in the world, covering 11.7 million km2. Samoa’s exclusive economic zone (E.E.Z.) is the smallest in the region due to a quirk of geography and the Government is currently locked in negotiations to change its maritime boundaries, a top fisheries official has said.

Although the oceans are technically viewed as international zones, meaning no one country has jurisdiction over it all, there are regulations in place to help keep the peace and to essentially divide responsibility for the world’s oceans to various entities or countries around the world.