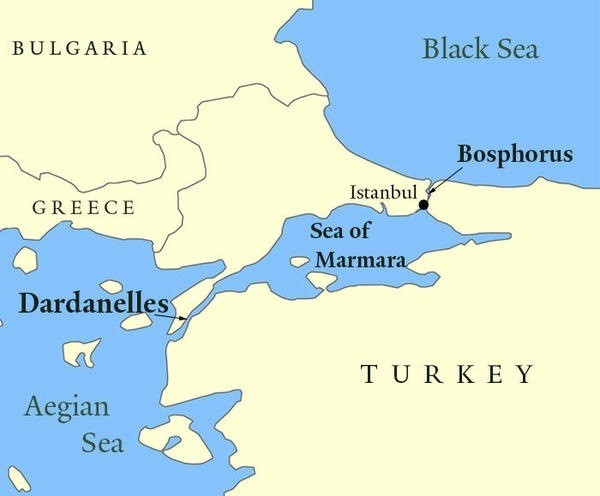

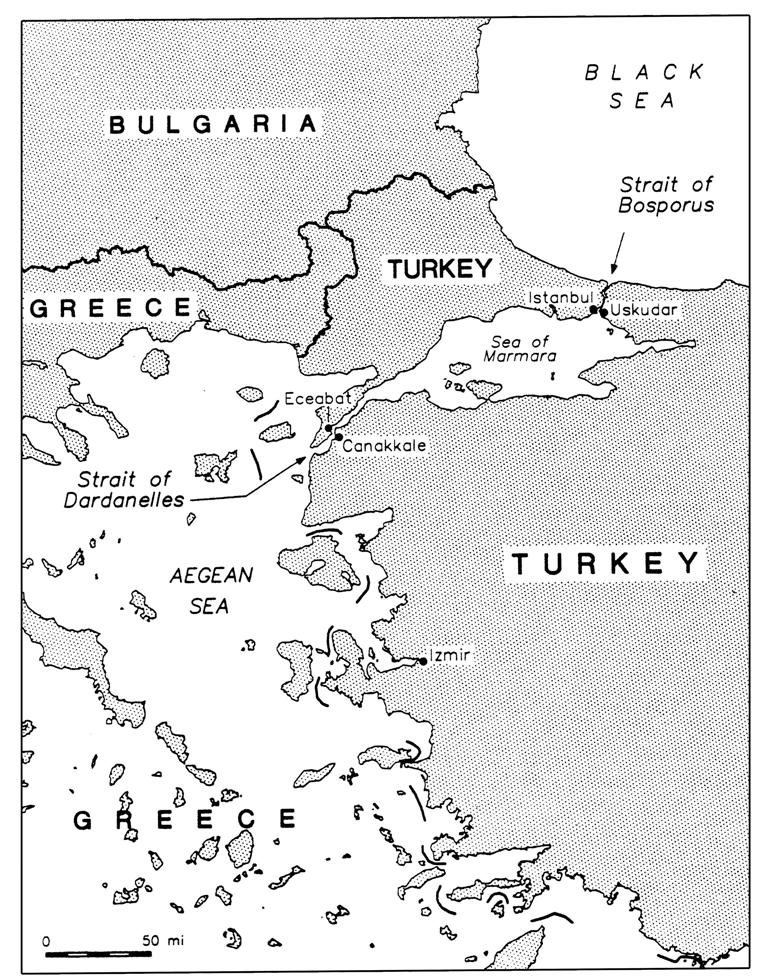

These straits, also known as the Turkish Straits or the Black Sea Straits, connect the Aegean Sea and the Black Sea via the Sea of Marmara. The Bosporus connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara, while the Dardanelles connects the Aegean Sea with the Sea of Marmara. The Bosporus is about 17 miles long and varies in width between one-third and 2 miles. The Dardanelles is about 35 miles long, its width decreases from 4 miles at the Aegean to about 0.7 miles at its narrowest; its depth varies from 160 to 320 feet. The Sea of Marmara is about 140 miles long. (See Map 30.)

The Turkish Straits are governed by the Montreux Convention of July 20, 1936 and therefore fall under the article 35(c) exception of the LOS Convention which states that the legal regime of straits regulated in whole or in part by a long-standing international convention in force is not altered by the LOS Convention. Under the Montreux Convention, merchant vessels, whatever their cargo or flag, enjoy complete freedom of transit, day or night. Pilotage and towage are optional. The passage of warships of Black Sea and non-Black Sea states is restricted in different ways depending on the type of warship and whether or not Turkey is a belligerent. There is no right of international overflight of the Turkish Straits.

The strait has always been of great strategic and economic importance as the gateway to Istanbul and the Black Sea from the Mediterranean.The Bosphorus strait has played a major role in world trade for centuries. It connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Marmara and eventually, through the Dardanelles strait, with the Mediterranean. About 48,000 vessels transit the straits each year, making this area one of the world’s busiest maritime gateways. Until early 1970’s the Turkish Straits were known as a rich and productive marine area. The Straits also used to play an important role as a biological corridor between the Mediterranean and the Black Sea, and acted as an acclimatization zone for the Mediterranean species.

Map 30. Bosporus and Dardanelles.

As mentioned in the preamble, the Convention annulled the previous Lausanne Treaty on the Straits, which stated the demilitarization of the Greek islands of Lemnos and Samothrace along with the demilitarization of the Dardanelles, the Sea of Marmara and the Bosporus, and the Turkish islands of İmroz, Bozcaada and Tavşan.

The Convention consists of 29 Articles, four annexes and one protocol. Articles 2–7 consider the passage of merchant ships. Articles 8–22 consider the passage of war vessels. The key principle of freedom of passage and navigation is stated in articles 1 and 2. Article 1 provides, “The High Contracting Parties recognise and affirm the principle of freedom of passage and navigation by sea in the Straits”. Article 2 states, “In time of peace, merchant vessels shall enjoy complete freedom of passage and navigation in the Straits, by day and by night, under any flag with any kind of cargo.”

The International Straits Commission was abolished, authorising the full resumption of Turkish military control over the Straits and the refortification of the Dardanelles. Turkey was authorised to close the Straits to all foreign warships in wartime or when it was threatened by aggression. Also, it was authorised to refuse transit from merchant ships belonging to countries at war with Turkey.

A number of highly-specific restrictions were imposed on what type of warships are allowed passage. Non-Black-Sea powers willing to send a vessel must notify Turkey 15 days prior of their sought passing, while Black Sea states must notify within 8 days of passage. Also, no more than nine foreign warships, with a total aggregate tonnage of 15,000 tons, may pass at any one time. Furthermore, no single ship heavier than 10,000 tonnes can pass. An aggregate tonnage of all non-Black Sea warships in the Black Sea must be no more than 45,000 tons (with no one nation exceeding 30,000 tons at any given time), and they are permitted to stay in the Black Sea for no longer than twenty-one days. Only Black Sea states may transit capital ships of any tonnage, escorted by no more than two destroyers.

Under Article 12, Black Sea states are also allowed to send submarines through the Straits, with prior notice, as long as the vessels have been constructed, purchased or sent for repair outside the Black Sea. The less restrictive rules applicable to Black Sea states were agreed as, effectively, a concession to the Soviet Union, the only Black Sea state other than Turkey with any significant number of capital ships or submarines.The passage of civil aircraft between the Mediterranean and Black Seas is permitted but only along routes authorised by the Turkish government.

The terms of the Convention were largely a reflection of the international situation in the mid-1930s. They largely served Turkish and Soviet interests, enabling Turkey to regain military control of the Straits and assuring Soviet dominance of the Black Sea. Although the Convention restricted the Soviets’ ability to send naval forces into the Mediterranean Sea, thereby satisfying British concerns about Soviet intrusion into what was considered a British sphere of influence, it also ensured that outside powers could not exploit the Straits to threaten the Soviet Union. That was to have significant repercussions during World War II when the Montreux regime prevented the Axis powers from sending naval forces through the Straits to attack the Soviet Union.[citation needed] The Axis powers were thus severely limited in naval capability in their Black Sea campaigns, relying principally on small vessels that had been transported overland by rail and canal networks.

Auxiliary vessels and armed merchant ships occupied a grey area, however, and the transit of such vessels through the straits led to friction between the Allies and Turkey. Repeated protests from Moscow and London led to the Turkish government banning the movements of “suspicious” Axis ships with effect from June 1944 after a number of German auxiliary ships had been permitted to transit the Straits.

Aircraft carriers

Although the Montreux Convention is cited by the Turkish government as prohibiting aircraft carriers from transiting the straits, the treaty actually contains no explicit prohibition on aircraft carriers. However, modern aircraft carriers are heavier than the 15,000 ton limit imposed on warships, making it impossible for non-Black Sea powers to transit modern aircraft carriers through the Straits.

Under Article 11, Black Sea states are permitted to transit capital ships of any tonnage through the straits, but Annex II specifically excludes aircraft carriers from the definition of capital ship. In 1936, it was common for battleships to carry observation aircraft. Therefore, aircraft carriers were defined as ships that were “designed or adapted primarily for the purpose of carrying and operating aircraft at sea.” The inclusion of aircraft on any other ship does not classify it as an aircraft carrier.

The Soviet Union designated its Kiev-class and Kuznetsov-class ships as “aircraft-carrying cruisers” because these ships were armed with P-500 and P-700 cruise missiles, which also form the main armament of the Slava-class cruiser and the Kirov-class battlecruiser. The result was that the Soviet Navy could send its aircraft-carrying cruisers through the Straits in compliance with the Convention, but at the same time the Convention denied access to NATO aircraft carriers, which exceeded the 15,000 ton limit.

Turkey chose to accept the designation of the Soviet aircraft carrying cruisers as aircraft cruisers, as any revision of the Convention could leave Turkey with less control over the Turkish Straits, and the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea had already established more liberal passage through other straits. By allowing the Soviet aircraft carrying cruisers to transit the Straits, Turkey could leave the more restrictive Montreux Convention in place.

Controversies

Soviet Union

The Convention remains in force, but not without dispute. It was repeatedly challenged by the Soviet Union during World War II and the Cold War. As early as 1939, Joseph Stalin sought to reopen the Straits Question and proposed joint Turkish and Soviet control of the Straits, complaining that “a small state [i.e. Turkey] supported by Great Britain held a great state by the throat and gave it no outlet”. After the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact was signed by the Soviet Union and Nazi Germany, the Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov informed his German counterparts that the Soviet Union wished to take military control of the Straits and establish its own military base there. The Soviets returned to the issue in 1945 and 1946, demanding a revision of the Montreux Convention at a conference excluding most of the Montreux signatories, a permanent Soviet military presence and joint control of the Straits. That was firmly rejected by Turkey, despite an ongoing Soviet “strategy of tension”. For several years after World War II, the Soviets exploited the restriction on the number of foreign warships by ensuring that one of theirs was always in the Straits, thus effectively blocking any state other than Turkey from sending warships through the Straits. Soviet pressure expanded into full demands to revise the Montreux Convention, which led to the Turkish Straits crisis of 1946, which led to Turkey abandoning its policy of neutrality. In 1947, it became the recipient of US military and economic assistance under the Truman Doctrine of containment and joined the NATO alliance, along with Greece, in 1952.

United States

The passage of US warships through the Straits also raised controversy, as the convention forbids the transit of non-Black Sea nations’ warships with guns of a calibre larger than eight inches (203 mm). In the 1960s, the US sent warships carrying 420 mm calibre ASROC missiles through the Straits, prompting Soviet protests. The Turkish government rejected the Soviet complaints, pointing out that guided missiles were not guns and that since such weapons had not existed at the time of the Convention, they were not restricted.

According to Antiwar.com news editor Jason Ditz, the Montreux Convention is an obstacle to US Naval buildup in the Black Sea because of its stipulations regulating warship traffic by nations not sharing Black Sea coastline. The US thinktank Stratfor has written that these stipulations place Turkey’s relationship to the US and its obligations as a NATO alliance member in conflict with Russia and the regulations of the Montreux Convention.

Militarisation of the Greek islands

The Convention annulled the previous Lausanne Treaty on the Straits, including the demilitarization of the Greek islands of Lemnos and Samothrace. Greece’s right to militarise them was recognized by Turkey, in accordance with the letter sent to the Greek Prime Minister on 6 May 1936 by the Turkish Ambassador in Athens at the time, Ruşen Eşref, upon instructions from his Government. The Turkish government reiterated this position when the then Turkish Minister for Foreign Affairs, Rüştu Aras, in his address to the Turkish National Assembly on the occasion of the ratification of the Montreux Treaty, unreservedly recognized Greece’s legal right to deploy troops on Lemnos and Samothrace, with the following statement: “The provisions pertaining to the islands of Limnos and Samothrace, which belong to our neighbor and friendly country Greece and were demilitarized in application of the 1923 Lausanne Treaty, were also abolished by the new Montreux Treaty, which gives us great pleasure”.

After the relationship between the countries deteriorated over the next decades, Turkey denied that the treaty affected the Greek islands, seeking to bring back into force the relevant part of the Lausanne Treaty on the Straits.

1994 reforms

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which entered into force in November 1994, has prompted calls for the Montreux Convention to be revised and adapted to make it compatible with UNCLOS’s regime governing straits used for international navigation. However, Turkey’s longstanding refusal to sign UNCLOS has meant that Montreux remains in force without further amendments.

The safety of vessels passing through the Bosporus has become a major concern in recent years as the volume of traffic has increased greatly since the Convention was signed: from 4,500 in 1934 to 49,304 by 1998. As well as obvious environmental concerns, the Straits bisect the city of Istanbul, with over 14 million people living on its shores and so maritime incidents in the Straits pose a considerable risk to public safety. The Convention does not, however, make any provision for the regulation of shipping for the purposes of safety and environmental protection. In January 1994, the Turkish government adopted new “Maritime Traffic Regulations for the Turkish Straits and the Marmara Region”. That introduced a new regulatory regime “to ensure the safety of navigation, life and property and to protect the environment in the region” but without violating the Montreux principle of free passage. The new regulations provoked some controversy when Russia, Greece, Cyprus, Romania, Ukraine and Bulgaria raised objections. However, they were approved by the International Maritime Organization on the grounds that they were not intended to prejudice “the rights of any ship using the Straits under international law”. The regulations were revised in November 1998 to address Russian concerns.

Is the Bosporus man made?

Bosphorus strait is a natural strait, located in northwestern Turkey, connecting the Black Sea to the Sea of Marmara. Also known as the Strait of Istanbul, this water way links the European part of the city from its Asian part and thus remains as a very strategic waterway in the region.

How wide is Bosporus and Dardanelles?

The width is 1400 meters and the depth is 109 meters. Dardanelles; It is less indented from the Bosphorus. It is twice the length of the Istanbul Strait. Here, the deepest place, as in the Bosphorus, at the same time the narrowest place is between Kilitbahir and Çanakkale.