Background

For 35 years between 1965 and 1999, the fisheries relations have been governed

by the Fisheries Agreement of 1965, whereby both countries established

their respective 12 N.M. exclusive fisheries zones from the coasts of

each State; a joint regulation zone outside Korea’s exclusive fisheries zone

and a joint resources research zone outside the joint regulation zone.

It is generally understood that the Fisheries Agreement of 1965 between

Korea and Japan was negotiated under the influence of UNCLOS I and II

where the argument to give the coastal States exclusive or preferential

fisheries rights over the waters up to 12 miles had been very strong, although

the argument fell short of getting a necessary majority for producing such

rules. In the 1960s it was Japan who wanted to have a fisheries agreement

concluded with Korea because Korea proclaimed the so-called “Peace line”

in a vast area of the sea around the Korean Peninsula in 1952 and enforced

the line against the Japanese fishing vessels. By concluding the fisheries

agreement, the Japanese government succeeded in rendering the Peace line

inapplicable to its fishermen and thus the Japanese fishermen gained access

to fisheries resources even within the Peace line as long as they did not fish

within the 12-mile fisheries zone of Korea. Although there were some restrictions

in the joint regulation zone as to the number and size of fishing vessels,

types of fishing gear, time of fishing operations, there had not been

serious disputes in the zone because the maximum catch had been set at

such a high level so as to satisfy the need for the Japanese fishermen and the enforcement over the vessels in the joint regulation was to be exercised solely by the flag State of the vessels.

However, problems began to arise in the late 1970s as the Korean

fishing vessels became much more active in the waters off the Japanese

coast with improved power and fishing equipment thanks to modern technology.

In this situation, the proclamation of the 200-mile fisheries zone

by the Soviet Union in 1976 also provided a backdrop against which new

fisheries disputes arose anew because the Korean distant water fishing vessels

that lost their fishing ground in the waters around the Soviet Unions

in Northwest Pacific began to swamp the coastal areas of Japan’s Hokkaido

to catch Alaska Pollock. Although this situation was not welcomed at all

by Japan which also proclaimed its 200-mile fisheries zone in 1977, it could

not enforce the zone against Korean fishermen in the waters beyond the 12

miles from its coasts because of the Fisheries Agreement of 1965, which

provided for, as Japan had wished, the freedom of fishing under the flag State jurisdiction in the area beyond 12 miles from the coasts. Then the Fisheries Agreement of 1965 turned out to benefit Korean fishermen more

than Japanese fishermen. Obviously this was not the situation which Japan

had expected in the 1960s when it asked Korea to conclude a fisheries

agreement.

In this situation Japan raised the need to amend the Fisheries Agreement

of 1965 but Korea tried to keep the agreement as it stood because it benefited

Korean fishermen. However, after long discussion, Korea and Japan reached

a compromise formula in 1980, establishing zones where certain types of

fishing regulations were to be applied. The zones were established in the

waters around Korea’s Cheju island, Japan’s Kyushu and Hokkaido.

According to the regulation scheme, Japanese fishermen were to apply

fishing regulations in the designated waters around the island of Cheju and

Korean fishermen were to apply fishing regulations in the designated waters

around Kyushu and Hokkaido of Japan. Although the fishing regulations

were agreed between the two governments, this type of fishing regulation

was named “autonomous fishing operation regulation measures” because

fishing vessels operating in the areas where the measures were to be applied

were subject only to the jurisdiction of the State under whose flag the vessels

flew. Due to the fact that flag State jurisdiction was applied in the

autonomous fishing operation regulation zones, the autonomous fishing

operation scheme was not intended to replace the 1965 agreement but to

complement it on the basis of Articles 1 and 4 of the agreement, which

made it clear that the enforcement jurisdiction in the waters beyond the 12-

mile fisheries belonged only to the flag States.

However, the autonomous fishing regulation scheme was not fully successful

in preventing fisheries disputes arising between Korean and Japan.

This was particularly so with regard to fishing activities by Korean fishermen

in the waters around the Japanese island of Hokkaido, as some of the

Korean fishing vessels sometimes did not faithfully observe the autonomous

fishing operation regulations. There was even antagonism among the Japanese

local fishermen of Hokkaido against the Korean fishing vessels because the

Japanese fishermen applied their own conservation measures in the waters

even beyond 12 miles from the Japanese coasts whereas some of the Korean

fishing vessels appeared not to have due regard to the Japanese conservation

measures, thus making the Japanese conservation efforts much less

effective. Therefore, the local fishermen and politicians from Hokkaido took

the initiative for abolishment of the agreement of 1965 in the mid-1990s

and establishment of a new fisheries agreement with Korea.

In 1996 when Japan and Korea proclaimed their respective EEZ Japan

began to emphasise the need to abolish the Fisheries Agreement of 1965 and conclude a new fisheries agreement on the basis of the EEZ fisheries regime in accordance with the LOS Convention. In March 1996, three

Japanese ruling parties jointly declared their position that “a new fisheries

agreement between Japan and Korea should be concluded within a year”.

In the face of the Japanese proposals for a new fisheries agreement, Korea

voiced its position that a new fisheries agreement should be established

based upon the delimitation of EEZ boundaries, and thus the delimitation

of EEZ boundaries should come first. The question whether the delimitation

of EEZ or provisional fisheries agreements should come first became

a heated issue between Korea and Japan even in the summit talks between

the two countries. In the summit meeting of 25 January 1997, the Japanese

Prime Minister, Ryutaro Hashimoto, asked the Korean President, Youngsam

Kim, for co-operation from the Korean side for attainment of an objective

of concluding a new fisheries agreement within the year 1997, arguing

that the delimitation of EEZ boundaries should not be a prerequisite for

concluding a new fisheries agreement.

In March 1997 the Korean side presented a proposal of an outline of

a new fisheries agreement, which provided that a new fisheries agreement

should come into effect after Korea and Japan agreed on the delimitation

of EEZ boundaries and that the level of current fishing catch should be respected

for five years after the coming into effect of the new fisheries agreement.

Various proposals were exchanged since March 1997 between Korea

and Japan. At this time, Korea appears to have tried hard to get an agreement

on an EEZ boundary line between Korea and Japan because the

momentum for the delimitation of an EEZ boundary would be significantly

lessened if the EEZ boundary were not drawn now before the conclusion

of a new fisheries agreement. When the delimitation of an EEZ boundary

was proven difficult to do before the conclusion of a new fisheries agreement,

the Korean government proposed in September 1997 to draw a provisional

fisheries boundary following the equidistance line between Korea’s

Ulleung-Do and Japan’s Oki-syto. But the Japanese side did not accept this

proposal. Since November 1997 Korea and Japan have begun to discuss

in detail the shape and extent of joint fishing zones and the zones where

EEZ fisheries regime is to be applied. In January 1998 as the Japanese

government notified its intention to terminate the Fisheries Agreement of

1965, the agreement of 1965 was doomed to be terminated on 22 January

1999, a year after the notification. After hard negotiations conducted at

various levels, Korea and Japan reached an agreement on a new fisheries

agreement in September 1998 on the basis of modified 35-mile EEZ fisheries

zones of each country and establishment of joint fishing zones outside the EEZ fisheries zones. The new fisheries agreement was signed on 28 November 1998 in Kagoshima, Japan and the instruments of ratification

were exchanged on 22 January 1999 in Seoul, Korea bringing the new

agreement into effect on the same day.

Main Features of the New Fisheries Agreement between Korea and Japan

Basic Structure of the Agreement

The Agreement of 1999 is agreed not upon the ultimate EEZ boundaries

but upon the provisional joint fishing zones and EEZ fisheries zones of a

limited extent which are to be considered as each Party’s EEZ for the purpose

of implementation of the agreement. As such, there is no doubt that

the agreement is a provisional arrangement of a practical nature envisaged

in Paragraph 3 of Article 74 of the LOS Convention pending the ultimate

agreement on boundaries of EEZ. Thus the agreement purports to regulate

fisheries relations between Korea and Japan pending the ultimate delimitation

of EEZ boundaries between the two countries. Related to this, the

agreement obliges the two countries “to continue to negotiate in good faith

for an earlier delimitation of the exclusive economic zone”. The “without-

prejudice clause” of the agreement provides a quite comprehensive protection

of the positions of each Party, providing that: “Nothing in this

Agreement shall be deemed to prejudice the position of each Contracting

Party relating to issues on international law other than matters on fisheries”.

Here it will be appropriate to examine the basic structure of the new

agreement. As the new agreement is based on the EEZ fisheries regime,

Article 1 of the agreement provides that: “This Agreement applies to the

exclusive economic zone of the Republic of Korea and the exclusive economic

zone of Japan”. Then, Articles 2 to 6 of the agreement provide

detailed provisions on fishing access of fishing vessels of one Party to the

EEZ of the other Party. Each Party shall permit nationals and fishing vessels

of the other Party to harvest in its exclusive economic zone pursuant

to the agreement and its relevant laws and regulations (Article 2). Each

Party may take necessary measures in accordance with international law in

its exclusive economic zone to ensure that nationals and fishing vessels of

the other Party engaged in fishing activities in its exclusive economic zone

comply with the fisheries agreement, its relevant law and regulations and

specific conditions imposed upon them (Article 5).

However, since there is no EEZ boundary between Korea and Japan

the agreement deals with the question of what are the geographical limits of the EEZ of each Party in applying the provisions on EEZ fishing access. In this regard, the Parties agreed to use the Northern Continental Shelf

Boundary of 1974 as a fisheries boundary for the purpose of the application

of the agreement (Paragraph 2 of Article 7). Thus the continental shelf

boundary is now also a fisheries boundary even if it is a provisional one.

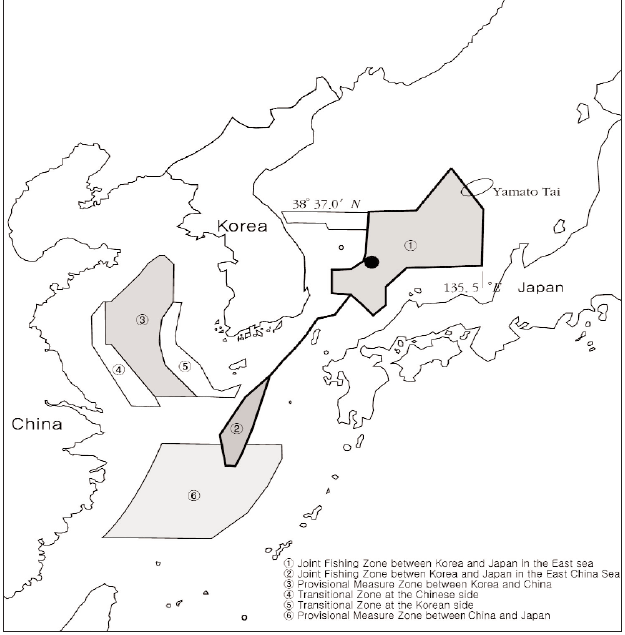

And for the waters where there is no continental shelf boundary, Korea and

Japan agreed to set up two joint fishing zones; one is in the East Sea connected

to the northern terminus of the Northern Continental Shelf Boundary

and the other is in the East China Sea connected to the southern terminus

of the Shelf Boundary (Article 9).

The agreement makes it clear that the provisions of Articles 2 to 6 on

EEZ fishing access do not apply to the joint fishing zones (Article 8). The

lines constituting the outer limits of the joint fishing zones are to be considered

as geographical limits for the exercise of sovereign rights for the

purpose of application of the agreement by each State (Annex II). Therefore

each Party is to exercise EEZ fisheries rights against the other Party under

the agreement in the area situated between the outer limits of its territorial

sea and the outer limits of the joint fishing zones on its side. This is a sort

of presumption on the fisheries boundaries using the outer limits of the joint

fishing zones. However, one exception to this assumption is provided for

the area where the fisheries relations between North Korea and Japan are

concerned (Paragraph 3 of Annex).

Article 9 does not attempt to name the two joint fishing zones, and thus

there are no official names for the two zones. However, the Korean government

favours the term “middle zones” or “intermediate zones”, whereas the

Japanese government prefers the term “provisional zones”. Detailed provisions

are laid down on the management of marine living resources in the

two joint fishing zones (Annex I).

Korea and Japan set up “Korea-Japan Fisheries Committee” to consult

and render recommendations and binding decisions to both governments

on the various matters relating to the implementation of the agreement

(Article 12). The Committee can make recommendations or decisions only

through an agreement between the representatives of the Parties participating

in the Committee (Paragraph 2 of Article 12). The range of issues

that the Committee may deal with is very broad. The Committee may consult

and render recommendations, inter alia, on matters relating to EEZ fishing

access such as the species of fish allowed to be caught, quotas of catch,

areas of fishing and specific conditions on fishing operations (Articles 3

and Article 12). The Committee can consult also on the matters relating to

the State of marine living resources in the two joint fishing zones. However, a distinction was deliberately made between the joint fishing zone in the East Sea and the joint fishing zone in the East China Sea in this regard. That

is to say that the Committee can make only recommendations with regard

to conservation and management of marine living resources in the East Sea,

whereas it can even make decisions with regard to the same matters in the

joint fishing zone in the East China Sea. This distinction is crucial to the

Korean government because it wishes to avoid the impression that Korea

and Japan take “joint” measures with regard to the waters around Dok-do,

which is “an inherent part of Korean territory”, and is “geographically”

of Dok-do in the middle of the “middle zone” in the East Sea appears to

be intolerable to some Korean people. Therefore, on the basis of this distinction

the government of the Republic of Korea explained to the Korean

people that the middle zone in the East Sea is not “jointly” managed by

Korea and Japan, whereas the middle zone in the East China Sea is “jointly”

managed by Korea and Japan.

The dispute settlement procedures are also provided in the agreement

mentioning arbitration procedure in detail. However, unlike the Fisheries

Agreement of 1965, the arbitration envisaged in the new fisheries agreement

is not compulsory; only through the consent of both Parties can disputes

be brought to arbitration (Article 13). These provisions on dispute

settlements can have a significant impact when a dispute arises and the dispute

relates to the provisions of the LOS Convention as well as the new

fisheries agreement. In the case where such a dispute arises and either Party

wishes to bring the case before an arbitral court constituted under the LOS

Convention, then it is highly probable that the other Party can successfully

challenge the jurisdiction of the arbitral court as did Japan in the Southern

Bluefin Tuna Arbitration of 2000. It was Japan who preferred to provide

for consensual arbitration, whereas Korea wished to reproduce the compulsory

arbitration clause in the Fisheries Agreement of 1965.

Shaping of the Joint Fishing Zones (Intermediate Zones)

Korea and Japan needed to establish the two joint fishing zones in the East

Sea and in the East China Sea because they did not reach an agreement on

delimitation of their overlapping EEZ claims. In other words, if Korea and

Japan succeeded in drawing EEZ boundaries then the fisheries agreement

could have been simpler than the one they have now. It took more than two

years of intensive negotiations for Korea and Japan to reach an agreement

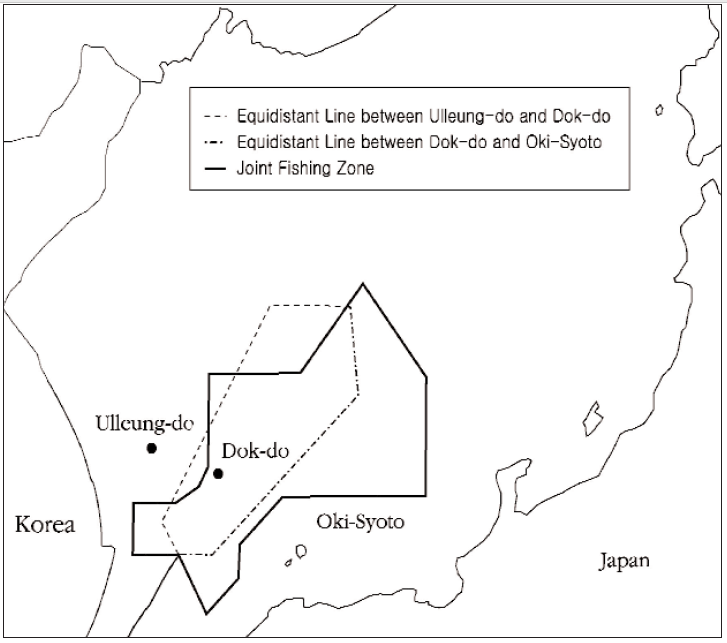

in shaping the outer limits of two joint fishing zones. In shaping the joint

fishing zone in the East Sea, the following elements were considered: 35-mile lines from the coasts, in particular from Ulleung-do and Oki-syto, the line of Lat. 38° 37.0′ E. being the northern limits line between South

Korea and North Korea, the line of Lat. 135.5° E. as the eastern limits of

the joint fishing zone, the location of Yamato Tai which is an important

squid fishing ground, and the basepoints which were used in making the

northern terminus (Point No. 35) of the Northern Continental Shelf Boundary.

However, the most important consideration in shaping the joint fishing zones

was the equitable division of the zones which are regarded as EEZ of each

Party for the purpose of application of the fisheries agreement.

With regard to the shaping and location of the Intermediate Zone in

the East Sea, a serious question arose as to whether the Intermediate Zone

had an effect on the territorial issue of Dok-do. However, it seems absurd

to assume that the provisional fisheries agreement between Korea and Japan

based upon Article 74(3) of the LOS Convention affects a territorial issue,

since the “without-prejudice clause” clearly provides that: “Nothing in this

Agreement shall be deemed to prejudice the position of each Contracting

Party relating to issues on international law other then matters on fisheries”.

It is to be recalled that in the Minquiers and Ecrehos Case where the

French government tried to reinforce its position by using a bilateral fisheries

agreement of 1839, arguing that the Minquires and Ecrehos groups were

included in the common fisheries zone, the ICJ held that:

The Court does not consider it necessary, for the purpose of deciding the

present case, to determine whether the waters of the Ecrehos and Minquires

groups are inside or outside the common fishery zone established by

Article 3. Even if it be held that these groups lie within this common

fishery zone, the Court cannot admit that such an agreed common fishery

zone in these waters would involve a regime of common use of the land

territory of the islets and rocks, since the Articles relied on refer to fishery

only and not to any kind of use of land.

Here, however, another associated question lingers as to whether the joint

fishing zone in the East Sea can be seen as a precedent where Dok-do is

excluded from being used as a basepoint. It can be said that Dok-do was

not used as Korea’s basepoint in shaping the joint fishing zone in the East

Sea, in the sense that the joint fishing zone could have been established to

the east of Dok-do if it had been used as Korea’s basepoint. But at the same

time by the same token, it can be said that Dok-do was not used as a

Japanese basepoint in shaping the joint fishing zone. If Dok-do had been

used as a Japanese basepoint then the joint fishing zone could have been

situated somewhere between Ulleung-do and Dok-do. Let us approach the question from a different angle: Can the location and shape of the joint fishing zone be seen as a precedent where either Korea or Japan denounce

its claims to use Dok-do as its basepoint? From close examination of the

map, it can be said that the shaping of the joint fishing zone is a precedent

where Japan’s claim to use Dok-do was denounced whereas Korea’s claim

is not. Note that some part of the median line between Ulleung-do and Dokdo,

which could have been argued by Japan in the delimitation negotiation

is located to the west of the joint fishing zone, i.e., in Korea’s EEZ, whereas

the median line between Dok-do and Oki-syto is well within the joint fishing

zone.

Korea might be tempted to stress this aspect of the location of the joint

fishing zone if Japan argues to use Dok-do as its basepoint in the maritime

delimitation. However, again it is to be recalled that both countries are free

from the possible precedence in the Fisheries Agreement, as Article 15 of

the Fisheries Agreement provides that:

Nothing in this Agreement shall be deemed to prejudice the position of

each Contracting Party relating to issues on international law other than

matters on fisheries.

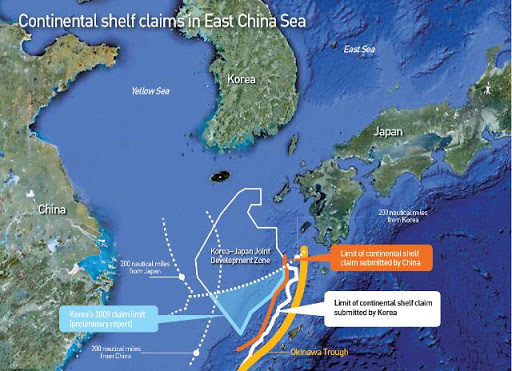

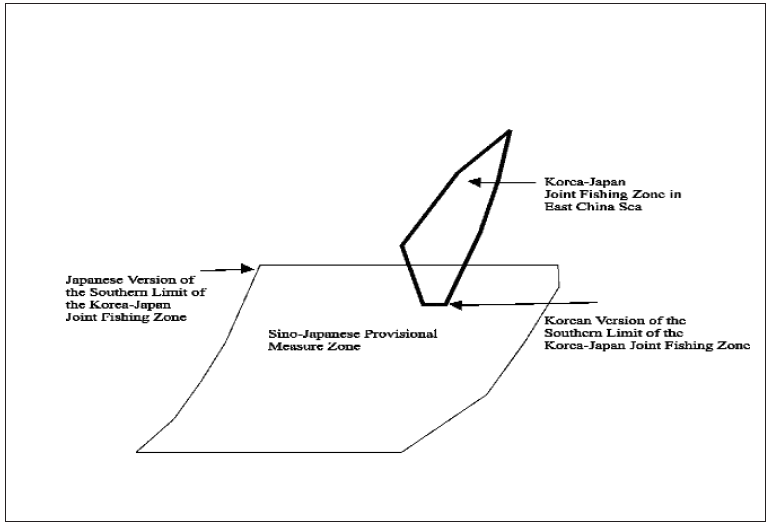

Now let us turn to the joint fishing zone in the East China Sea. The outer

limits of the zone are adopted in such a way as to include the two following

hypothetical water column boundaries between Korea and Japan: one

is the equidistance line drawn by using all the nearest features in the coasts

of Korea and Japan in the region whether they are rocks or islands, and the

other is a line drawn by excluding rocks in terms of Paragraph 3 of Article 121 of the LOS Convention. Even after having agreed to include two such lines in the joint fishing zone, Korea and Japan had further difficulty in

agreeing on the co-ordinates of the southern limits of the joint fishing zone

in the East China Sea, because there were different views on the southernmost

point of the water column boundaries between Korea and Japan.

Korea’s basic position in this regard is that the water column boundary in

the East China Sea between Korea and Japan should be drawn in such a

way as not to produce a cut-off effect for Korea. Thus the boundary should

reach the 200 mile line from Korea’s southernmost island Mara-do and the

southern limits of the joint fishing zone should be identical with the 200-

mile line from Mara-do. For Japan it was also difficult to agree with

Korea’s position particularly because Japan and China had already concluded

a fisheries agreement in November 1997 thereby establishing a

joint fishing zone in the East China Sea which encroaches upon the 200-

mile line from Mara-do. As they could not agree on the specific co-ordinates

of the southern limits of the joint fishing zone in the East China Sea,

they agreed to adopt the term “the southern-most parallel of the exclusive

economic zone of the Republic of Korea” to describe the southern limits

of the joint fishing zone in the East China Sea with a mutual understanding

that different views on the southern limits of the joint fishing zone in

the East China Sea exist between Korea and Japan. Thus for Korea the

southern limits line of the joint fishing zone in the East China Sea is at the

parallel of Lat. 29° 43′ N. in line with the 200-mile line from Mara-do,

whereas for Japan the line would be at the parallel somewhere of Lat. 30°

40′ N. following the latitude of a hypothetical tri-equidistant point among

Korea’s Mara-do, Japan’s Tori-shima and China’s Haijiao. Note that China’s

position on the delimitation of maritime boundaries is not for the equidistance

principle but for equitable principles particularly with regard to the

East China Sea and it did not participate in the negotiation on the shaping

of the Korea-Japan joint fishing zone in the area. In this context, China

expressed its position that it does not recognise the Korea-Japan joint fishing

zone in the East China.

Jurisdiction in the Joint Fishing Zones

The separate provisions on the two joint fishing zones with respect to the

jurisdiction therein and to the conservation and management of the marine

living resources thereof are almost identical except that the Korea-Japan

Fisheries Committee can make decisions with regard to the joint fishing

zone in the East China Sea whereas it can only make recommendations with

regard to the joint fishing zone in the East China Sea. It will be appropriate to examine the exceptional difference between the two zones and then to discuss the common aspects of the two zones with respect to jurisdiction

in the zones and conservation and management of the marine living resources

of the zones.

As mentioned earlier the difference is deliberately made by, and meaningful

to, Korea. Korea wished to avoid any implication that the joint fishing

zone in the East Sea where Dok-do is geographically situated is jointly

managed by Korea and Japan. The Korean government’s position on this

point is that the joint fishing zone in the East Sea is not a zone jointly managed

by Japan and Korea, because it would be either Korea alone or Japan

alone, which decides any conservation and management measures in the

joint fishing zone in the East Sea and thus the Korea-Japan Fisheries

Committee, which is an international juridical body, does not have any prescriptive

competence with regard to the joint fishing zone in the East China

Sea. Here, the Korean government appears to presuppose that the joint

fishing zone might affect the territorial issue if it is jointly managed by the

joint committee. An important question arises here: if the joint fisheries

committee has the competence to prescribe any conservation measures with

regard to the zone in the East Sea and thus the zone is to be called a “joint

management” zone, then does the competence of the joint committee affect

territorial status of Dok-do? It seems unreasonable to suggest that a joint

fishing zone affects sovereignty over an island if its fisheries resources are

jointly managed by the fisheries committee and that the zone does not affect

a territorial issue if the committee has no power to decide on the conservation

of fisheries resources in the zone. Interestingly, however, a few Korean

scholars have argued that the new fisheries agreement between Korea and

Japan affects negatively Korea’s territorial sovereignty of Dok-do. However,

it would be absurd to assume that a provisional fisheries agreement such

as the one between Korea and Japan affects the issue of territorial sovereignty.

As we discussed elsewhere, the clear distinction should be made

between a joint fishing zone or joint development zone and condominium,

since the former is related to sovereign rights and the latter is related to

sovereignty. We need to recall the provisions of Paragraph 3 of Article 74,

the without-prejudice clause in the agreement and the dicta of the ICJ in

the Minquiers and Ecrehos Case. If a provisional fisheries agreement can

affect territorial issues against the clear intentions of the Parties notwithstanding

all the safeguards, then no country in the world would venture to

conclude a provisional fisheries agreement fearing that the provisional agreement

would affect its position on the delimitation of EEZ boundaries, even

when there is no territorial dispute.

Now let us turn to the common aspects of the two joint fishing zones.

The fundamental common aspect is that the flag-State jurisdiction is applied

in the two joint fishing zones. It is provided in identical terms that: “Each

Contracting party shall not apply its relevant laws and regulations on fisheries

to the nationals and fishing vessels of the other Contracting Party in the

zone”. And even if there is a conservation measure adopted by a decision

by the Korea-Japan Fisheries Committee, it is up to each Party to take any

necessary measures upon its nationals and fishing vessels. However, an

indirect form of co-operation in enforcement can be made in these joint

fishing zones if there is a measure adopted by the Committee or a measure

adopted by each State in accordance with recommendations by the Committee:

in the case where a Party finds a fishing vessel of the other Party engaged

in fishing in violation of such a measure, the Party notifies the violation to

the other Party, and then the other Party should take necessary measures

with regard to the violation by its fishing vessels and report back to the

Party of the measures it has taken. However, such indirect co-operation

has not happened thus far because the Korea-Japan Fisheries Committee

has not yet made any recommendation or decision. The reason why the

Committee has not made any recommendation with regard to the conservation

and management of the living resources in the joint fishing zone in

the East Sea, is that Korea has been reluctant to agree on any measure in

the face of a domestic criticism that the status of Dok-do is impaired because

of the establishment of the joint fishing zone in the East Sea. And it appears

that there has been no serious discussion on the conservation and management

of the joint fishing zone in the East China Sea.

It seems appropriate to discuss further the issue of the conservation

and management of the living resources in the joint fishing zone in the East

Sea because this issue has been the most controversial issue in the discussion

of the Korea-Japan joint fisheries committee. In the zone in the East

Sea, the main species caught are squids, Spanish mackerel and large crab.

Korean fishermen increased their catch in the joint fishing zone in the East

Sea after the Korea-Japan fisheries agreement came into effect because their

catch in the waters which was part of the high seas and turned into Japan’s

EEZ fisheries zone decreased significantly. Against this backdrop, Japan

asked Korea that the joint committee should adopt a number of conservation

measures and some form of enforcement co-operation with regard to

the joint fishing zone in the East Sea. However, Korea refused to adopt any

conservation measure or even placing a ceiling on the number of fishing

vessels per mode in the zone, which is an example of a conservation

measure in the fisheries agreement. In the negotiations of 1999 between Korea and Japan for the fishing quotas and fishing conditions in each other’s EEZ in 2000, Japan argued that unless the effective conservation measure

is agreed with regard to the middle zone in the East Sea, then the negotiations

on fishing quotas in the EEZ cannot be made. But surprisingly Korea

responded to Japan saying that it would not agree to adopt any conservation

measure through recommendation of the joint committee with regard

to the East Sea joint fishing zone, because it might affect its territorial ownership

over Dok-Do, even if it gave up its fishing quota in Japan’s EEZ. In

this dramatic confrontation, both countries agreed in 1999 that each Party

should implement its own conservation measures under the principle of

flag-State jurisdiction in the joint fishing zones and that autonomous fishing

regulations of non-governmental nature may be agreed and implemented

through the consultation between their fishermen’s organisations. It is not

reasonably expected that Korea would agree to adopt any conservation measures

in the joint committee with regard to the joint fishing zone in the East

Sea because of its unyielding position on this issue influenced by the public

worries about the possible implications of conservation measures on

Dok-do.

In this regard, a question is raised in this author’s mind as to whether

Japan is really interested in proper management of the marine living resources

in the Korea-Japan joint fishing zone in the East Sea. Because notwithstanding

Japan’s strong demands for the adoption of conservation measures

through the joint committee, Japan agreed with China that it would allow

Chinese fishermen to fish up to 7,000 tons of squid annually in the middle

of the Korea-Japan joint fishing zone in the East Sea without consultation

with Korea. Also note that Japan has never asked to adopt a conservation

measure in the Korea-Japan fishing zone in the East China Sea. Now a further

question can arise: is it Japan’s hidden intention, as the Korean public

worries, to take some advantage in territorial issues over Dok-do from

the fisheries agreement? The answer is unknown to this author. But one

thing is very clear. The provisional fisheries agreement cannot affect territorial

questions at all as we have discussed fully thus far.

The Korea-Japan Fisheries Agreement and the Fishing Order in the East China Sea

As the “Provisional Measure Zone” between Japan and China overlaps with

the Korean version of the joint fishing zone in the East China Sea, there

arises a need to address this problem in the negotiations between Korea

and Japan. If this problem is not to be solved in one way or another, then

jurisdictional conflicts could occur in the East China Sea. Suppose that a Korean fishing vessel is engaged in the overlapped zone on the presumption that it is only subject to the jurisdiction of the Korean authorities, since

it is part of the Korea-Japan joint fishing zone in accordance with the provisions

of the Korea-Japan fisheries agreement. Suppose also that a military

ship or coast guard ship of China or Japan finds the Korean vessel

engaged in fishing in the zone and tries to enforce its fisheries laws on the

Korean vessel. In this situation, a jurisdictional conflict could take place

when a ship from the Korean Maritime Police Agency comes along and

argues that it has the sole jurisdiction over the Korean fishing vessel under

the principle of the flag-State jurisdiction, provided in the Korea-Japan

fisheries agreement. To avoid such jurisdictional conflicts, Korea and Japan

Minutes, the Korean government expressed its “intention to co-operate with

the government of Japan in order not to damage fisheries relations established

by Japan and a third country in a certain area of the East China Sea

(emphasis added)”. In this passage the third State seems to imply China

because China is the only country relevant in this context. However, it is

not clear from its ordinary meaning what the term “a certain area of the

East China Sea” indicates. However, in the light of the fact that the Agreed

Minutes were intended to deal mainly with the problem of overlap between

the Korean version of Korea-Japanese joint fishing zone in the East China

Sea and the Sino-Japanese provisional measure zone, it can be reasonably

assumed that the term “a certain area” indicates the part of the Korean version

of the Korea-Japanese joint fishing zone which is located within the

Sino-Japanese provisional measure zone.

Thus interpreted, Korea’s intention in the Agreed Minutes can be seen

as a compromise from its position with regard to the location of the southern

limits line of the Korea-Japanese joint fishing zone and also to its challenge

of the legality of the northern limit line of the Sino-Japanese provisional

measure zone. Therefore, immediately after this undertaking is made it is

provided that: “However, this shall not be deemed to prejudice the position

of the Republic of Korea on the fisheries agreement concluded by Japan

with such a third country”.

In the same document, the Japanese government also made an important

quid pro quo non-binding undertaking, saying that it has “an intention

to co-operate with the Government of such a third country in order to render

possible certain fishing activities by nationals and fishing vessels of the

Republic of Korea in the other certain area of the East China Sea under

the fisheries relations established by Japan and the third country (emphasis

added)”. As the Agreed Minutes do not show where “the other certain area” in the East China Sea is located, the need arises to figure out where it is. Firstly, it is clear that “the other certain area” is an area that does not

belong to “a certain area” where Korea is willing to co-operate with Japan

in order not to damage fisheries relations between Japan and China. Thus,

the part of the Korean version of the Korea-Japanese joint fishing zone

which is located in the Sino-Japanese provisional measure zone is excluded

from consideration. Secondly, it should be noted that the Japan’s undertaking

is related to co-operation with a third State (China) for allowing the

fishing activities by Korean fishermen. Thus it can be assumed that the

other certain area is an area where both China and Japan have some rights

over fisheries and where Japan cannot exercise the rights alone. Therefore

it can be assumed that “the other certain area” is located inside the Sino-

Japanese provisional measure zone but outside the aforementioned “a certain

area”.

Korea and Japan jointly expressed in the Agreed Minutes their intention

“to negotiate specific ways for maintenance of good fisheries order in

the East China Sea” through the three separate joint fisheries committees

between Korea, Japan and China. Therefore, the role of the three joint fisheries committees between Korea, China and Japan is expected to maintain a good fishing order in the East China Sea where the three coastal

States made overlapping claims of EEZ.