The Aegean dispute is a set of interrelated controversies between Greece and Turkey over sovereignty and related rights in the region of the Aegean Sea. … Turkish claims of “grey zones” of undetermined sovereignty over a number of islets, most notably the islets of Imia.

In the Golden Age of Greece and beyond, the Aegean Sea continued to serve an important function in trade and in war, helping the Greek culture and civilization to flourish until the Romans, like the Sea Peoples before them, employed the waterways for conquest and subdued Greece.

Turkey and Greece being the two littoral states have legitimate rights and interests in the Aegean Sea. These involve their security, economy and other traditional rights recognized by international law. As others have mentioned the Greek state only got control of most of the islands as late as the end of WWII. That was when the Dodecanese joined Greece. The reason why the islands are Greek is because Turkey or the Ottomans before it didn’t much care for them.

The Aegean dispute is a set of interrelated controversies between Greece and Turkey over sovereignty and related rights in the region of the Aegean Sea. This set of conflicts has strongly affected Greek-Turkish relations since the 1970s, and has twice led to crises coming close to the outbreak of military hostilities, in 1987 and in early 1996. The issues in the Aegean fall into several categories:

The delimitation of territorial waters,

The delimitation of national airspace,

The delimitation of exclusive economic zones and the use of the continental shelf,

The role of flight information regions (FIR) for the control of military flight activity,

The issue of the demilitarized status assigned to some of the Greek islands in the region,

Turkish claims of “grey zones” of undetermined sovereignty over a number of islets, most notably the islets of Imia.

One aspect of the dispute is the differing interpretations of the maritime law: Turkey has not signed up to the Convention on the Continental Shelf nor the superseding United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, both of which Greece has signed up to; as such, Turkey doesn’t recognize a legal continental shelf and EEZ around the Greek islands.

Between 1998 and the early 2010s, the two countries came closer to overcoming the tensions through a series of diplomatic measures, particularly with a view to easing Turkey’s accession to the European Union. However, differences over suitable diplomatic paths to a substantial solution remained unresolved, and as of 2021 tensions remain.

Abstract of Aegean Territorial Waters Conflict An Evolutionary Narrative article

Delimitation of the territorial waters and continental shelf in the Aegean Sea constitutes a constant source of conflict and produces recurrent crises between Greece and Turkey. This article explores directions that the Greek-Turkish dispute over the delimitation of territorial waters can take through an evolutionary game framework. Crises are found to follow routines and practices involving challenges to the status quo and reactions preceding mutual retreat. Hence, the status quo in the Aegean Sea can persist even in the form of aggressive behavior. It is also possible that the dispute will evolve into a stable state of conflict where no cooperative foreign policy can survive.

- Maritime Jurisdiction

The first category of the outstanding Aegean issues is related to the maritime jurisdiction areas, including the territorial waters and the continental shelf and their delimitation.

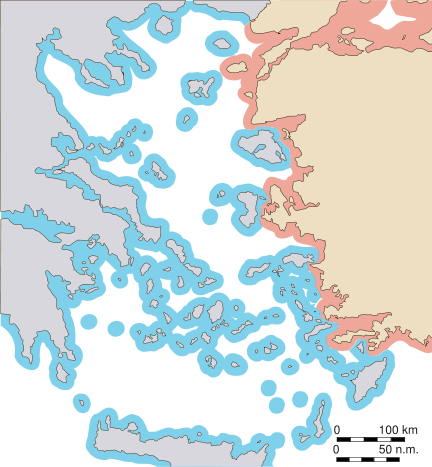

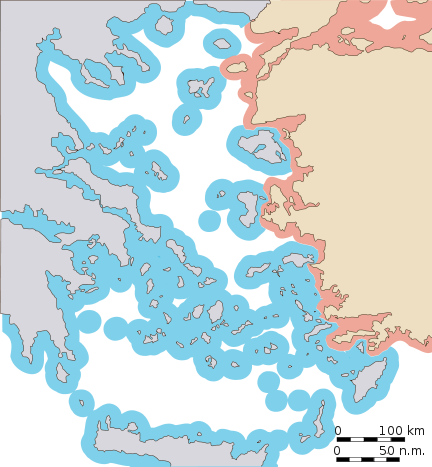

The maritime boundaries between Turkey and Greece have yet to be delimited by agreement. At present, the breadth of territorial sea of both Turkey and Greece in the Aegean is 6 nautical miles. The geographical relationship of the coasts of Turkey and Greece in the Aegean is adjacent and at the same time opposite which requires boundary delimitation.

It is a fundamental rule of international law that delimitation of maritime boundaries between adjacent and opposite states in locations where maritime areas overlap or converge should be effected by agreement on the basis of international law.

In the case of the Aegean, however, there exists no maritime delimitation between Turkey and Greece with respect to the territorial sea in the area of adjacent coasts as well as between opposite coasts.

Extension of territorial waters to 12 nautical miles will disproportionately alter the balance of interests in the Aegean Sea to the detriment of Turkey. At present, due to its many islands, Greek territorial waters make up about 40% of the Aegean Sea. In the case of 12 nautical miles wide territorial waters, the ratio rises to over 70%. In the case of extension of territorial waters to 12 nautical miles, Turkey’s territorial waters remain less than 10% of the Aegean Sea while the size of the high seas falls from 51% to 19%.

The second aspect of the outstanding Aegean issues over the maritime jurisdiction areas in the Aegean is the delimitation of the continental shelf between Turkey and Greece.

The Continental Shelf areas in the Aegean that appertain to Turkey and Greece have yet to be delimited. At present neither country possesses delimited maritime jurisdiction area on the Aegean continental shelf beyond their 6 nautical miles territorial sea.

The subject of the dispute is “delimitation as between Turkey and Greece of the continental shelf areas of the Aegean Sea, beyond the respective 6 nautical miles territorial sea of the two littoral states, which appertain to each of them”.

- Aegean airspace

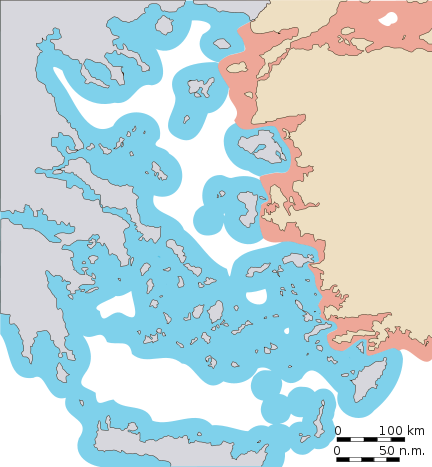

The second category of the outstanding Aegean disputes is related to Aegean airspace the core causes of which are both the Greek claim to 10 nautical miles national airspace and the F.I.R. (Flight Information Region) responsibility by Greece.

Greece’s claim to 10 NM national airspace constitutes the reason behind the Aegean airspace disagreement. The core aspects of this dispute are the “Flight Information Region” (FIR) responsibility by Greece and the unique Greek claim of 10 NM national airspace while the breadth of its territorial waters is 6 NM. In international law, the boundary of territorial sea of a state also forms the boundary of its national airspace.

Greece exercises sovereignty in the air within 10 nautical miles of its coasts (by force of the Decree of 6 September 1931, in combination with laws 5017/1931, 230/1936 and 1815/1988). As a sovereign state, Greece chose to exercise sovereignty in the air within the 10 nautical miles of territorial waters it declared in 1931, regarding issues of aviation and its policing, whereas it decided to exercise sovereignty on the sea to 6 nautical miles (law 230/1936 and legislative decree 187/1973).

Turkey constantly violates claimed Greek national airspace with military aircraft – often armed – that also carry out low flights over inhabited islands. This conduct on the part of Turkey – beyond being a violation of Greek national airspace and having the potential to provoke heated incidents – creates hazards for civil aviation.

The exercising of sovereignty over airspace up to 10 nautical miles is implicitly legal, as it does not exceed the 12 nautical miles stipulated by the law of the sea as the greatest boundary of the breadth of territorial waters and national airspace.

From 1931 and for many decades Turkey accepted the breadth of Greek national airspace at 10 nautical miles without any objection or dispute, which qualifies under international law as tacit agreement. The 10-nautical mile status has been in force since 1931, when the relevant presidential decree was issued and implemented uniformly, without any protest as to its legal basis.

Turkey disputes the regime by invoking the non-coincidence of boundaries of sovereignty in the air and on the sea. Greece declared a 10 NM wide national airspace in 1931 even though the width of its territorial sea was 3 NM at that time. Greece later extended its territorial waters to the present 6 NM in 1936. Therefore, Turkey argues that Greece’s claim to 10 NM national airspace is against the rules of international law and the airspace between Greece’s 6 NM territorial waters and its declared 10 NM national airspace is part of the international airspace. Greece’s 6-10 NM airspace claim is not recognized internationally. Nor is it recognized by Turkey.

Turkey refuses to recognize a 10-mile airspace zone around Greek islands in the Aegean Sea, which led to over 1,200 airspace violations in 2015, 31 of which took place over Greek territory. On 24 November 2015, Turkey shot down a Russian jet over Syria for an alleged airspace violation. “The Turkish F-16 fighter jet was conducting a training flight over neutral waters. During its mission, two Greek air force F-16s began pursuing our fighter jet, holding it as a target on the radar for three minutes and 40 seconds,” the Turkish General Staff said in a statement.

Turkey had a long history of intruding Greek airspace, with incidents rising over the past several years, to 1,269 in 2014. Intruding flights over Greek territory more than doubled in 2015, compared to the previous year.

- Legal Status of Certain Geographical Features

The disagreement over the legal status of certain geographical features in the Aegean, in essence, is a dispute related to treaty interpretation. It concerns the legal status of certain geographical features and attribution of territorial sovereignty over them under treaty provisions governing the territorial status quo in the Aegean.

The dispute, thus, has arisen as a result of contesting claims of the parties emanating from differing interpretations related to the meaning, scope, intent and legal effect of the territorial provisions of the relevant and valid international instruments in this respect.

Turkey does not have any claim over the islands, islets or such features which were unambiguously ceded to Greece by internationally valid instruments. Yet, it is an incontestable fact that there are many islets and geographical features in the Aegean Sea whose sovereignty is not indisputably given to Greece. Some of those disputed geographical features lay very close to Turkey’s coast in the in the Aegean Sea. Actually this issue is one of the stumbling blocks before reaching a settlement as regards the delineation of maritime boundaries between the two countries.

- Demilitarized Status of the Eastern Aegean Islands

The fourth category of the outstanding Aegean issues is the demilitarized status of the Eastern Aegean Islands under relevant international instruments, including the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923 and the Paris Treaty of 1947.

The Eastern Aegean Islands are demilitarized by several international agreements, including but not limited to the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923 and the Paris Treaty of 1947. These international treaties which are in force and thus binding upon Greece strictly forbid the militarization of Eastern Aegean Islands and bring legal obligations and responsibilities to Greece to this end.

Article 13 of the 1923 Laussane Peace Treaty stipulated the modalities of the demilitarization for the islands of Lesvos, Chios, Samos, and Ikaria. It imposed certain restrictions related to the presence of military forces and establishment of fortifications which Greece undertook as a contractual obligation to observe stemming from this Treaty. The Convention of the Turkish Straits annexed to the Laussanne Treaty further defined the demilitarized status of the islands of Lemnos and Samothrace. It stipulated a stricter regime for these islands, due to their vital importance to the security of Turkey by virtue of their close proximity to the Turkish Straits.

The demilitarized status of Eastern Aegean Islands was once again confirmed in the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty. But Turkey is not a signatory state to this Treaty. The “Dodecanese Islands” namely Stampalia, Rhodes, Calki, Scarpanto, Casos, Piscopis, Nisiros, Calimnos, Leros, Patmos, Lipsos, Symi, Cos and Castellorizo were ceded to Greece on the explicit condition that they must remain demilitarized (Annex 6). The demilitarization of the Eastern Aegean Islands was due to the overriding importance of these islands for Turkey’s security. In fact, there is a direct linkage between the possession of sovereignty over those islands and their demilitarized status.

However, despite the protests of Turkey, Greece has been violating the status of the Eastern Aegean Islands by militarizing them in contravention of its contractual commitments and treaty obligations under international law. The dispute dates to 1974 when Athens started to militarize the islands off the Turkish coast in response to Turkey’s invasion of the Mediterranean island of Cyprus after a pro-Greek coup.

On the other hand, Greece also introduced a reservation to the compulsory jurisdiction of International Court of Justice on matters deriving from military measures concerning her “national security interests” when she accepted the Court’s jurisdiction in 1993. In so doing, Greece aimed to prevent a dispute concerning the militarization of the islands to be referred to the International Court of Justice. In the Turkish view, this is a tacit acceptance by Greece that she is violating her treaty obligations.

The demilitarized status of the Dodecanese islands was imposed after the decisive intervention of the Soviet Union and echoes Moscow’s political intentions at that point in time. It should, however, be noted that demilitarized status lost its raison d’être with the creation of NATO and the Warsaw Pact, as incompatible with countries’ participation in military alliances. Against this backdrop, demilitarized status ceased to apply to the Italian islands of Pantelaria, Lampedusa, Lampione and Linosa, as well as to West Germany on the one hand and Bulgaria, Romania, East Germany, Hungary and Finland on the other.

Greece, just like any other country in the world, has never ceded its natural right of defense in the event of a threat to its islands or any other part of its territory, especially since there has been sufficient proof over the past decades that Turkey is acting in an inconsistent manner and in violation of the United Nations Charter.

Turkey invaded Cyprus in 1974, in violation of the Cyprus Treaty of Guarantee, to which Greece is a signatory state, and despite the numerous United Nations Security Council and General Assembly Resolutions to the contrary, still continues to maintain substantial military forces in the occupied territories.

- Search and Rescue (SAR)

Search and Rescue services concerning maritime areas are regulated by the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue of 1979 (Hamburg Convention).

According to the Hamburg Convention, in case a search and rescue region cannot be established by agreement among Parties concerned, those Parties shall use their best endeavors to reach an agreement upon appropriate arrangements under which the equivalent overall co-ordination of search and rescue services is provided in the area. Such coordination has not been established in the Aegean despite Turkey’s repeated calls to this end.

Furthermore, stipulating that search and rescue regions should, in so far as practicable, be coincident with maritime search and rescue regions with respect to those over the high seas, Annex 12 of the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation makes a clear distinction between maritime and air search and rescue regions, and underlines the prevalence of the maritime dimension with regard to search and rescue operations conducted on high seas. Besides, search and rescue operations either they pertain to aircraft or vessels in distress are conducted at sea.

Against this background, Turkey has declared its search and rescue region and registered it in the relevant IMO documents, namely the IMO Global SAR Plan, and it continues to effectively conduct SAR activities/operations in the region defined therein with a view to saving human life.

Since the Turkish and Greek Search and Rescue Regions (SRR) partially overlap, all SAR efforts/activities to be conducted in these overlapping areas must be duly coordinated as appropriate, in accordance with the 1979 Hamburg Convention, Art. 2.1.5.