(a) Submarine Cables and Pipelines With respect to the freedom of use on the continental shelf, Article 79(1) stipulates that all States are entitled to lay submarine cables and pipelines on the continental shelf.

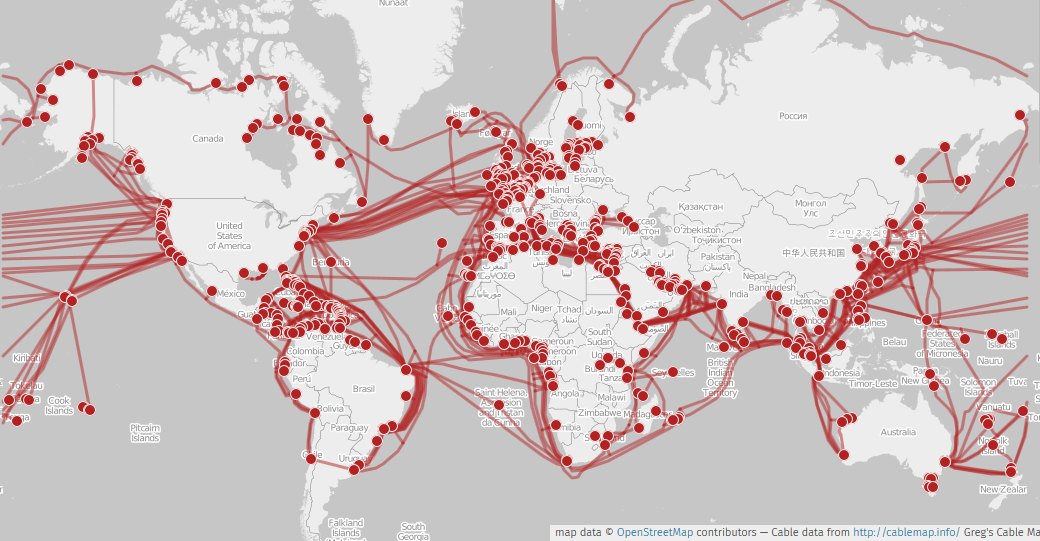

In practice, submarine cables are divided into two main categories: submarine power cables used to transmit electricity, and submarine communication cables used to transmit data communications traffic. At present, the overwhelming majority of the world’s international telecommunication relies on submarine fibre-optic cables, and submarine telecommunication cables have become a critical global communications infrastructure. The oil and gas pipeline is also of crucial importance as a reliable means of energy transport.

The delineation of the course for the laying of such pipelines on the continental shelf is subject to the consent of the coastal State pursuant to Article 79(3). Taken literally, the omission of submarine cables in this provision signifies that the delineation of the course for submarine cables is not subject to the consent of the coastal State. In reality, however, some coastal States require consent when third parties lay submarine cables in their EEZs or on their continental shelves. Under Article 79(4), the coastal State has the right to establish conditions for cables or pipelines entering its territory or territorial sea.

It can be argued that conditions for laying pipelines under Article 79(4) cover the enactment of legal requirement for protecting the environment. Under the same provision, the coastal State also has jurisdiction over the cables and pipelines constructed or used in connection with the exploration of its continental shelf, exploitation of its resources or the operations of artificial islands, installations and structures under its jurisdiction.

Under Article 79(2), the coastal State has rights to take reasonable measures for:

(i) the exploration of the continental shelf, (ii) the exploitation of its natural resources, and (iii) the prevention, reduction and control of pollution from pipelines, although it may not impede the laying or maintenance of such cables or pipelines. Thus, if a coastal State considers the laying of a pipeline on its continental shelf problematic, it can take reasonable measures to protect its interests in accordance with Article 79(2). In this connection, it is to be noted that while the first two types of measure apply to both submarine cables and pipelines, the third type of measure, i.e. for the prevention of marine pollution, does not apply to submarine cables. While the scope of ‘reasonable measures’ is not wholly unambiguous, it would seem reasonable for a coastal State to take measures to restrict the laying of submarine cables in environmentally sensitive areas, such as coral reefs or areas that have been designated for the exploitation of hydrocarbons on the continental shelf.

(b) The Judicial Nature of the Superjacent Waters Above the Continental Shelf In considering freedoms of third States, some mention should be made of the judicial nature of the superjacent waters above the continental shelf. Following Article 3 of the Convention on the Continental Shelf, Article 78(1) of the LOSC provides that the rights of the coastal State over the continental shelf do not affect the legal status of the superjacent waters or of the airspace above those waters. It follows that where the coastal State has not claimed an EEZ, the superjacent waters above the continental shelf are the high seas. Where the coastal State has established an EEZ, the superjacent waters above the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles are always the high seas under the LOSC. Hence all States enjoy the freedoms of navigation and fishing in the superjacent waters of the continental shelf and the freedom of overflight in the airspace above those waters. However, it must be noted that freedoms of third States may be qualified by the coastal State in the superjacent water of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles.

First, the coastal State has exclusive jurisdiction over the construction of artificial islands as well as installations and structures on the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles by virtue of Article 80 of the LOSC. In practice, artificial islands and other installations are constructed in superjacent waters above the continental shelf. It would seem to follow that freedom to construct artificial islands may be qualified by the coastal State jurisdiction, even though literally the superjacent waters of the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles are the high seas.

Second, in practice, coastal States explore and exploit natural resources on the continental shelf from the superjacent waters above the continental shelf. Accordingly, it appears inescapable that the coastal State excises its jurisdiction in the superjacent waters above the continental shelf for the purpose of the exploration and exploitation of natural resources. In fact, Article 111(2) of the LOSC provides the right of hot pursuit in respect of violations on the continental shelf, including safety zones around continental shelf installations, of the laws and regulations of the coastal State applicable to the continental shelf, including such safety zones. In practice, safety zones are established on the superjacent waters of the continental shelf. It would seem to follow that the coastal State jurisdiction relating to the exploration and exploitation of the continental shelf is to be exercised at least in safety zones on the superjacent waters of the shelf.

Third, as noted, the coastal State has jurisdiction with regard to marine scientific research on the continental shelf under Articles 56(1)(b)(ii) and 246(1) of the LOSC, and such research on the continental shelf is to be conducted with the consent of the coastal State pursuant to Article 246(2). On the other hand, Article 257 of the LOSC provides that all States have the right to conduct marine scientific research in the water column beyond the limits of the EEZ ‘in conformity with this Convention’. A question arises of whether the complete freedom of marine scientific research applies to superjacent waters of the continental shelf. According to a literal interpretation, consent under Article 246(2) seems to be required only for research physically taking place on the sea floor. Considering that normally marine scientific research is carried out from the superjacent waters or airspace above the continental shelf, however, it appears to be naïve to consider that coastal States will not exercise their jurisdiction to regulate marine scientific research there.

In summary, it appears that in some respects the freedom of the high seas may be qualified by coastal State jurisdiction in the superjacent waters above the continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles and the airspace above the waters. To this extent, their legal status should be distinguished from the high seas per se.