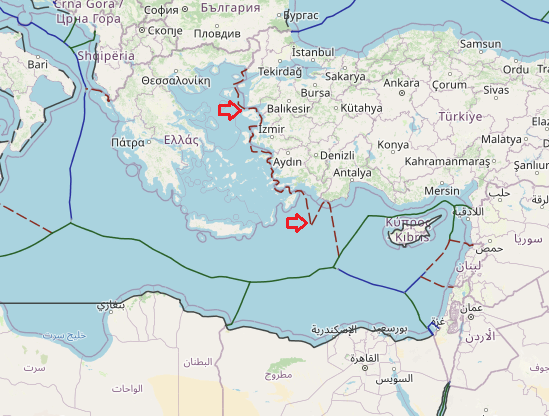

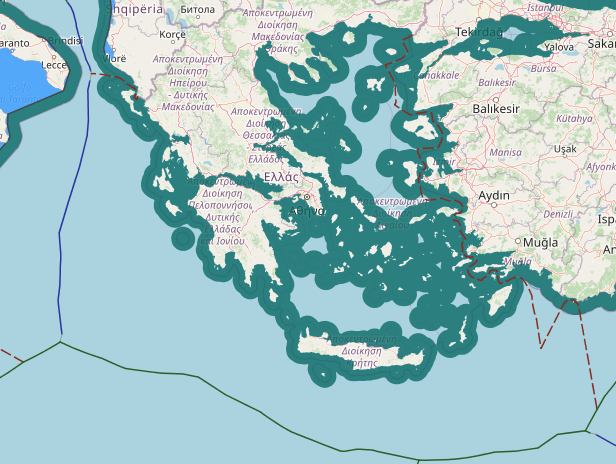

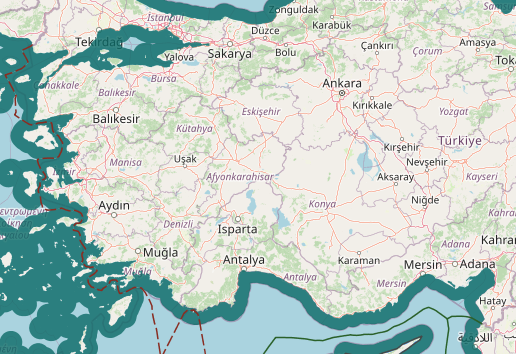

The delimitation of a maritime boundary between Greece and Turkey probably presents a more difficult problem than any other maritime boundary. The reason for this is that the Greek islands occupy most of the Aegean Sea and, with one exception, the eastern rampart of 15 islands lie less than 20 nm from the Turkish mainland. Turkey would be restricted to a very narrow coast zone no wider than 18 nm. While there is agreement that Greece holds sovereignty over these islands there is disagreement about how a maritime boundary should be delimited. Turkey objects to any suggestion that a line of equidistance would be appropriate. Turkey takes the view that equity is the over-riding principle in this case. It regards any arrangement that delivers most of the Aegean Sea and sea bed to Greece, on the basis of the small total areas and population of the Aegean Islands, as inequitable.

Turkey and Greece has Unsettled median lines between their own maritime borders. In 2018, Former Foreign Minister Nikos Kotzias said Greece is ready to extend its territorial waters from 6 to 12 nautical miles. In the first stage, he said, Greece will expand its sovereignty towards the west from the Diapontia Islands, a cluster of small islands in the Ionian Sea, to Antikythera, an island lying between the Peloponnese and Crete. But the plan is to also do the same in the Aegean.

Kotzias said that the move constitutes the “first extension of the country’s sovereignty since the Dodecanese became part of Greece in 1947.” Extension in the Ionian is unlikely to cause any objections from its neighbors Italy and Albania. But, the Aegean is a different proposition altogether. Turkey has threatened in the past that such a move, which it says in effect turns the Aegean into a Greek lake, is a cause of war (casus belli).

Territorial waters are an extension to the sea of the national sovereignty of a country beyond its shores. They are considered to be part of the country’s national territory.

They give the littoral state full control over air navigation in the airspace above, and partial control over shipping, although foreign ships (both civil and military) are normally guaranteed innocent passage through territorial waters.

Greece has a legal right to extend its territorial sea to 12 nautical miles, as provided for by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. Virtually all coastal states abide by the Law of the Sea, including Turkey, which since 1964 has expanded its territorial waters in the Black Sea and the Mediterranean to 12 nautical miles.

When ratifying the Convention, Greece tabled a statement declaring that “the time and place of exercising these rights … is a matter arising from its national strategy.” Successive Greek governments refrained from exercising this legal right. Six nautical miles have been in force since 1936, and since then there has been a continuing debate on whether Greece should extend to 12 nautical miles.

If Greece extends its territorial waters in the Aegean, it will increase its control from the current 43 percent to 71 percent. International waters will be reduced from 49 percent to less than 20 percent. This is why Turkey has threatened war. It claims that the Aegean is a special case and if the provisions of the Law of the Sea are applied, Turkey will be cut off from the Sea. Greece rejects Turkey’s arguments saying that under the Law of the Sea the right of passage is fully safeguarded and even expanded. By making use of these rights, even warships from other countries can move undisturbed from Greek territorial waters and through narrow passages between the islands, as is done today.

Tensions over the 12-mile question ran highest between the two countries in the early 1990s, when the Law of the Sea was going to come into force. On 9 June 1995, the Turkish parliament officially declared that unilateral action by Greece would constitute a casus belli. This declaration has been condemned by Greece as a violation of the Charter of the United Nations, which forbids “the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any state”.

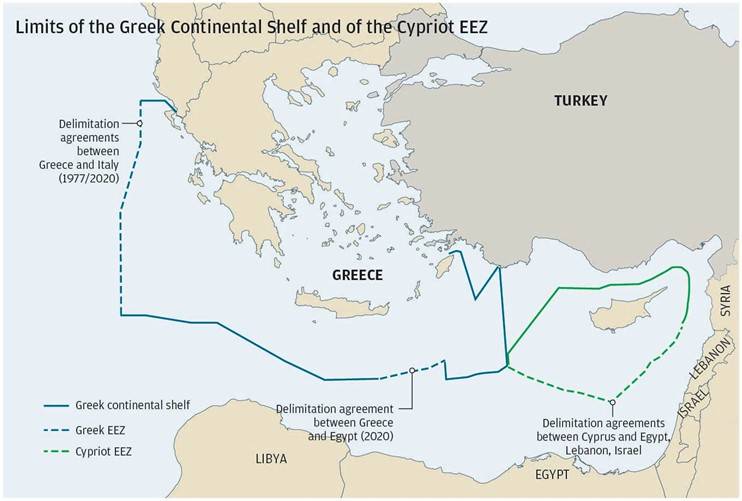

In last years Dispute on maritime jurisdiction areas based on Eastern Mediterranean hydrocarbon activities on the Turkey- Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) and Greek Cypriot State (GCA) and Greece axis, tensely continues.

The maritime jurisdiction disputes that have been going on in the Eastern Mediterranean for about 10 years have considerably escalated with the GCA and Greece’s recent activities. These activities are supported by global actors such as the EU, USA, Russia, France, and regional actors such as Israel and Egypt. The EastMed pipeline project and EMGF(Eastern Mediterranean Gas Forum); EEZ agreements signed by GCA with Egypt, Lebanon and Israel; GCA’s licensing and exploration activities in its unilaterally declared EEZ, pushed Turkey to make a strategic move. This agreement has been a major political shift and game changer on region’s geopolitics, energy order and global actor’s policies and plans for energy and political purposes in the Eastern Mediterranean. This study discusses

The basis of this conflict derives from the unresolved Cyprus Question and the Aegean dispute. The main conflict that Turkey experiences with the Greece in the Eastern Mediterranean is the delimitation of territorial waters and continental shelf as well as the Cyprus Question.

The Outstanding Aegean Issues

THE OUTSTANDING AEGEAN ISSUES

The outstanding issues in the Aegean Sea fall under mainly 5 categories:- First category of the outstanding Aegean issues is related to the maritime jurisdiction areas, including the territorial waters and the continental shelf and their delimitation.

a. Territorial Waters The maritime boundaries between Turkey and Greece have yet to be delimited by agreement. At present, the breadth of territorial sea of both Turkey and Greece in the Aegean is 6 nautical miles. The geographical relationship of the coasts of Turkey and Greece in the Aegean is adjacent and at the same time opposite which requires boundary delimitation. It is a fundamental rule of international law that delimitation of maritime boundaries between adjacent and opposite states in locations where maritime areas overlap or converge should be effected by agreement on the basis of international law. In the case of the Aegean, however, there exists no maritime delimitation between Turkey and Greece with respect to the territorial sea in the area of adjacent coasts as well as between opposite coasts. Extension of territorial waters to 12 nautical miles will disproportionately alter the balance of interests in the Aegean Sea to the detriment of Turkey. At present, due to its many islands, Greek territorial waters make up about 40% of the Aegean Sea. In the case of 12 nautical miles wide territorial waters, the ratio rises to over 70%. In the case of extension of territorial waters to 12 nautical miles, Turkey’s territorial waters remain less than 10% of the Aegean Sea while the size of the high seas falls from 51% to 19%. b. Continental Shelf The second aspect of the outstanding Aegean issues over the maritime jurisdiction areas in the Aegean is the delimitation of the continental shelf between Turkey and Greece. The Continental Shelf areas in the Aegean that appertain to Turkey and Greece have yet to be delimited. At present neither country possesses delimited maritime jurisdiction area on the Aegean continental shelf beyond their 6 nautical miles territorial sea. The subject of the dispute is “delimitation as between Turkey and Greece of the continental shelf areas of the Aegean Sea, beyond the respective 6 nautical miles territorial sea of the two littoral states, which appertain to each of them”.</code></pre></li>The second category of the outstanding Aegean issues is the demilitarized status of the Eastern Aegean Islands under relevant international instruments, including the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923 and the Paris Treaty of 1947.

The Eastern Aegean Islands are demilitarized by several international agreements, including but not limited to the Treaty of Lausanne of 1923 and the Paris Treaty of 1947.

These international treaties which are in force and thus binding upon Greece strictly forbid the militarization of Eastern Aegean Islands and bring legal obligations and responsibilities to Greece to this end.

However, despite the protests of Turkey, Greece has been violating the status of the Eastern Aegean Islands by militarizing them since the 1960's in contravention of its contractual commitments and treaty obligations under international law.

On the other hand, Greece also introduced a reservation to the compulsory jurisdiction of International Court of Justice on matters deriving from military measures concerning her "national security interests" when she accepted the Court’s jurisdiction in 1993. In so doing, Greece aims to prevent a dispute concerning the militarization of the islands to be referred to the International Court of Justice. In our view, this is a tacit acceptance by Greece that she is violating her treaty obligations. - The third category of the outstanding Aegean issues is the legal status of certain geographical features in the Aegean.

The disagreement over the legal status of certain geographical features in the Aegean, in essence, is a dispute related to treaty interpretation. It concerns the legal status of certain geographical features and attribution of territorial sovereignty over them under treaty provisions governing the territorial status quo in the Aegean. The dispute, thus, has arisen as a result of contesting claims of the parties emanating from differing interpretations related to the meaning, scope, intent and legal effect of the territorial provisions of the relevant and valid international instruments in this respect. Turkey does not have any claim over the islands, islets or such features which were unambiguously ceded to Greece by internationally valid instruments. Yet, it is an incontestable fact that there are many islets and geographical features in the Aegean Sea whose sovereignty is not indisputably given to Greece. Some of those disputed geographical features lay very close to Turkey’s coast in the in the Aegean Sea. Actually this issue is one of the stumbling blocks before reaching a settlement as regards the delineation of maritime boundaries between the two countries.</code></pre></li>The fourth category of the outstanding Aegean disputes is related to Aegean airspace the core causes of which are both the Greek claim to 10 nautical miles national airspace and the abuse of F.I.R. (Flight Information Region) responsibility by Greece contrary to international law.

Greece’s claim to 10 NM national airspace constitutes the reason behind the Aegean airspace disagreement. The core aspects of this dispute are the persistent abuse of “Flight Information Region” (FIR) responsibility by Greece and the unique Greek claim of 10 NM national airspace while the breadth of its territorial waters is 6 NM. In international law, the boundary of territorial sea of a state also forms the boundary of its national airspace. Greece declared a 10 NM wide national airspace in 1931 even though the width of its territorial sea was 3 NM at that time. Greece later extended its territorial waters to the present 6 NM in 1936. Therefore, Greece’s claim to 10 NM national airspace is against the rules of international law and the airspace between Greece’s 6 NM territorial waters and its declared 10 NM national airspace is part of the international airspace. Greece’s 6-10 NM airspace claim is not recognized internationally. Nor is it recognized by Turkey. The fifth category is related to Search and Rescue (SAR) operations/activities Search and Rescue services concerning maritime areas are regulated by the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue of 1979 (Hamburg Convention). According to the Hamburg Convention, in case a search and rescue region cannot be established by agreement among Parties concerned, those Parties shall use their best endeavors to reach an agreement upon appropriate arrangements under which the equivalent overall co-ordination of search and rescue services is provided in the area. Such coordination has not been established in the Aegean despite Turkey’s repeated calls to this end. Furthermore, stipulating that search and rescue regions should, in so far as practicable, be coincident with maritime search and rescue regions with respect to those over the high seas, Annex 12 of the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation makes a clear distinction between maritime and air search and rescue regions, and underlines the prevalence of the maritime dimension with regard to search and rescue operations conducted on high seas. Besides, search and rescue operations either they pertain to aircraft or vessels in distress are conducted at sea. Against this background, Turkey has declared its search and rescue region and registered it in the relevant IMO documents, namely the IMO Global SAR Plan, and it continues to effectively conduct SAR activities/operations in the region defined therein with a view to saving human life. Since the Turkish and Greek Search and Rescue Regions (SRR) partially overlap, all SAR efforts/activities to be conducted in these overlapping areas must be duly coordinated as appropriate, in accordance with the 1979 Hamburg Convention, Art. 2.1.5. (source: https://www.mfa.gov.tr/)

also we read from Greece government side:

Maritime boundaries between Greece and Turkey are clearly delimited.

More specifically:

the maritime region of the Evros estuary is delimited on the basis of the Athens Protocol of 26 November 1926.

in the adjoining maritime region extending south from Evros to Samos and Ikaria, in the absence of relevant agreements with Turkey, the principle of equidistance/median applies, in accordance with customary international law. According to Article 15 of the Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), , in the absence of a delimitation agreement, no state has the right to extend its territorial waters beyond the median line. This particular provision, which repeats, with minor drafting changes, Article 12(1) of the Geneva Convention on Territorial Waters and the Contiguous Zone, codifies customary law.

south of Samos, between the Dodecanese and the Turkish coast, the maritime boundaries are delimited based on the Agreement of 4 January 1932 and the Protocol of 28 December 1932, between Italy and Turkey. Greece was the successor state in the relevant provisions of these agreements, on the basis of Article 14(1) of the Paris Peace Treaty of 10 February 1947, which ceded sovereignty of the Dodecanese from Italy to Greece.

any contentions on the part of Turkey regarding the abovementioned existing status are unfounded and contravene international law. The delimitation agreements are in full force and are binding for Turkey, whereas in regions where there is no agreement on the maritime boundary, the principle of equidistance/median line is implemented based on customary law, which is valid erga omnes.

Greek-Turkish dispute over the delimitation of the continental shelf

Greek-Turkish disputes over the Aegean continental shelf date back to November 1973, when the Turkish Government Gazette published a decision to grant the Turkish national petroleum company permits to conduct research in the Greek continental shelf west of Greek islands in the Eastern Aegean.

Since then, the repeated Turkish attempts to violate Greece’s sovereign rights on the continental shelf have become a serious source of friction in the two countries’ bilateral relations, even bringing them close to war (1974, 1976, 1987).

In 1976, Greece brought this very serious issue before the UN Security Council and unilaterally resorted to the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in The Hague. Turkey refused to come before the Court, invoking its non-recognition of the Court’s jurisdiction. The Court did not examine the substance of the issue for reasons of formality, due to lack of competence.

The two countries launched negotiations on the issue of the continental shelf and in November 1976, signed the Berne procès-verbal setting out a framework for dialogue on the issue until it was submitted to the International Court. But this dialogue was inconclusive and ended in 1981 due to Turkey’s continuous vacillations and intransigent stance, thus the Berne procès-verbal – the validity and duration of which directly depended on the course of the negotiations – ceased to apply.

In March 2002, within the framework of the Greek-Turkish rapprochement inaugurated in 1999, the two sides agreed on a process of confidential exploratory contacts which are still ongoing, in order to find out whether and to what extent there is common ground and the conditions are in place to launch negotiations that might come to an agreement regarding the continental shelf in accordance with the Law of the Sea.

In case it seems no common ground can be found within a reasonable amount of time, Greece’s firm position – which coincides completely with international law and has been set as a prerequisite for Turkey’s accession course – is to bring the issue before the ICJ for resolution. But given that Turkey has not recognized the Court’s general, mandatory jurisdiction, a special agreement (an agreement to refer a dispute to arbitrators) is required that will constitute the legal basis for the ICJ’s jurisdiction.

Greece’s positions on the substance of the continental shelf issue and its limits are based on the applicable provisions of the Law of the Sea, both Contractual and Customary, which are the following:

• The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea provides for exclusive rights ipso facto and ab initio of a coastal state on its continental shelf which has a minimum breadth of 200 nautical miles, provided the distance between opposing coasts allows for this. Greece ratified this Treaty by Law 2321/1995, which according to the Constitution supersedes any provision to the contrary, and as the newest law takes precedence over any previous one.

• In accordance with Article 121 (2) of the Convention of the Law of the Sea all islands have a right to territorial waters, a contiguous zone, an exclusive economic zone and a continental shelf. These zone are determined in accordance with the general provisions of the Convention, as those are implemented in mainland regions. This general rule is also customary law and is thus also binding for the states that are not signatories to Convention. Therefore, all the Greek islands have a continental shelf in accordance with the Law of the Sea.

• Within this framework, an issue of delimitation of the continental shelf is only raised between the coast of Greek islands across from Turkey and the Turkish coast.

• With regard to the delimitation method, Greece’s firm position is that this delimitation must be based on international law, governed by the principle of equidistance/median line.

In this respect, it is noted that, according to article 156 of Law 4001/2011 (Government Gazette Α΄ 179 – “For the operation of electricity and gas energy markets, for exploration, production and transmission networks of hydrocarbons and other provisions”), in the absence of a delimitation agreement with neighbouring States, the outer limit of the continental shelf is the median line between the Greek coasts and the coasts opposite or adjacent to those. (source: https://www.mfa.gr/en/)