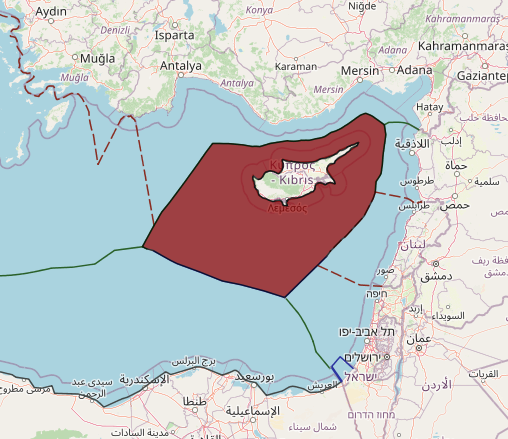

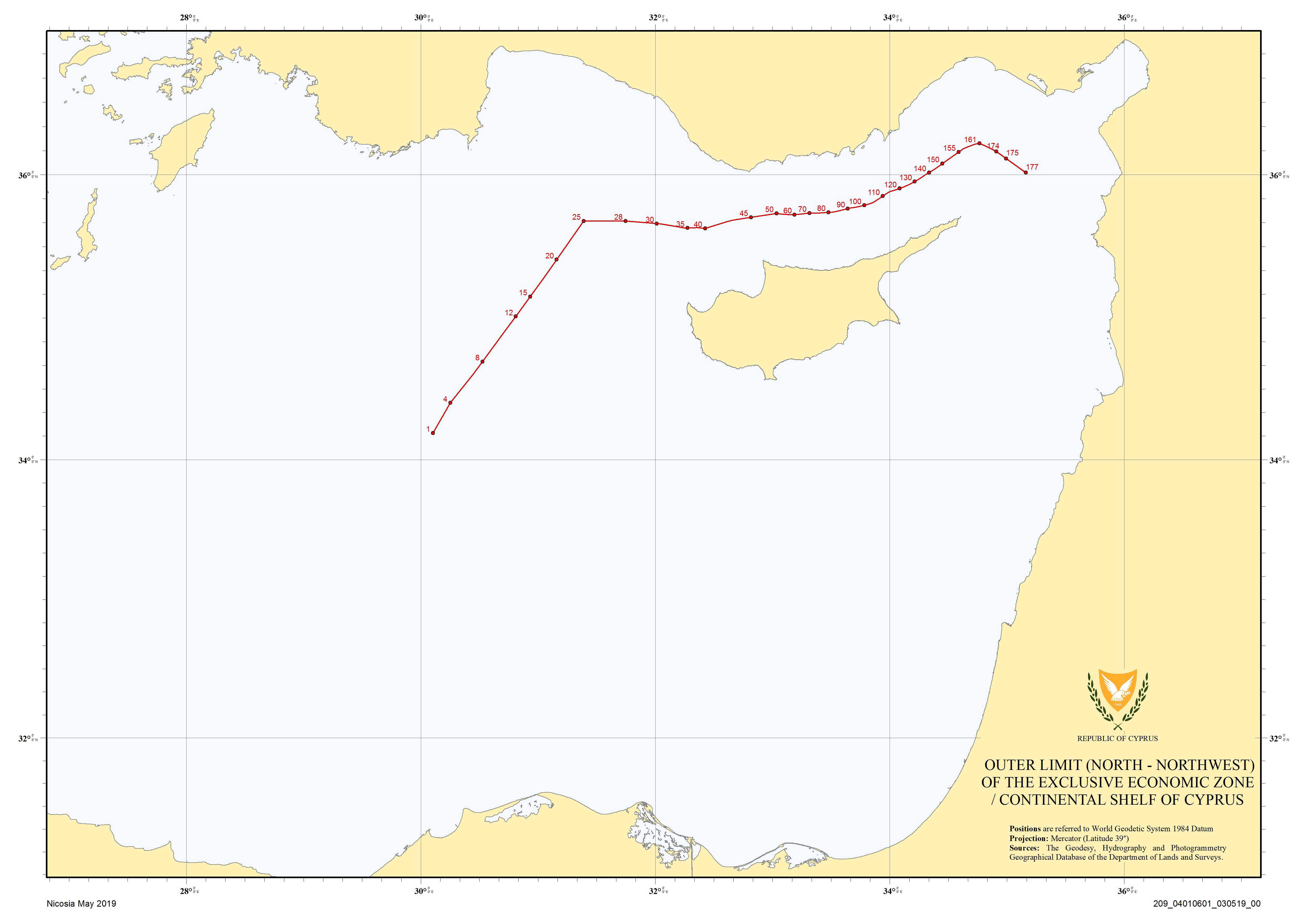

In accordance with international law (both UNCLOS and customary), the delimitation of the continental shelf or the EEZ between States with opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law in order to achieve an equitable result. Cyprus has repeatedly called upon Turkey to enter into negotiations for the delimitation of their maritime zones, in accordance with international law. This invitation to Turkey was, in fact, repeated in a letter addressed to the UN Secretary-General, on 12th December 2018. Turkey dismissed any efforts for a peaceful negotiation, and has resorted to actions that jeopardize and hamper the reaching of a final agreement, in violation of Articles 74(3) and 83(3) UNCLOS, which reflect customary principles such as good faith, self-restraint and peaceful settlement of disputes

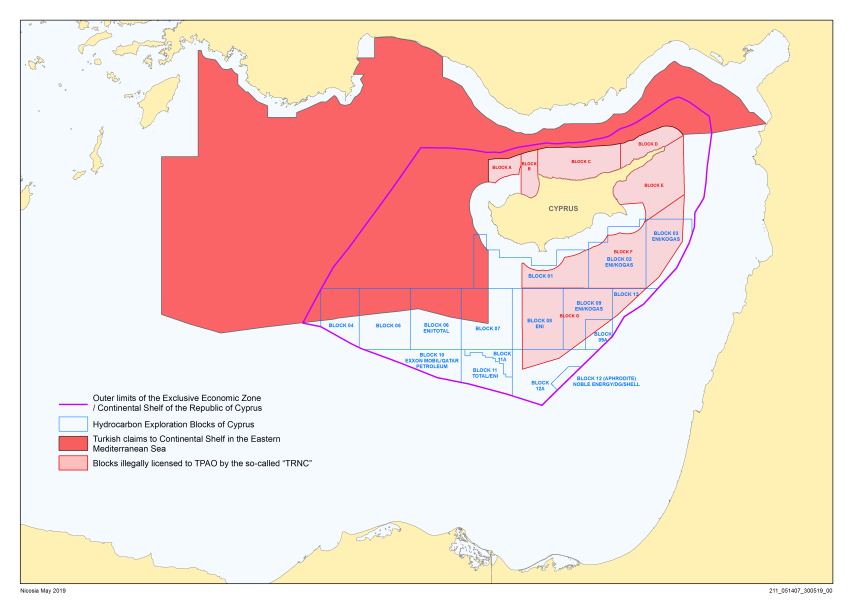

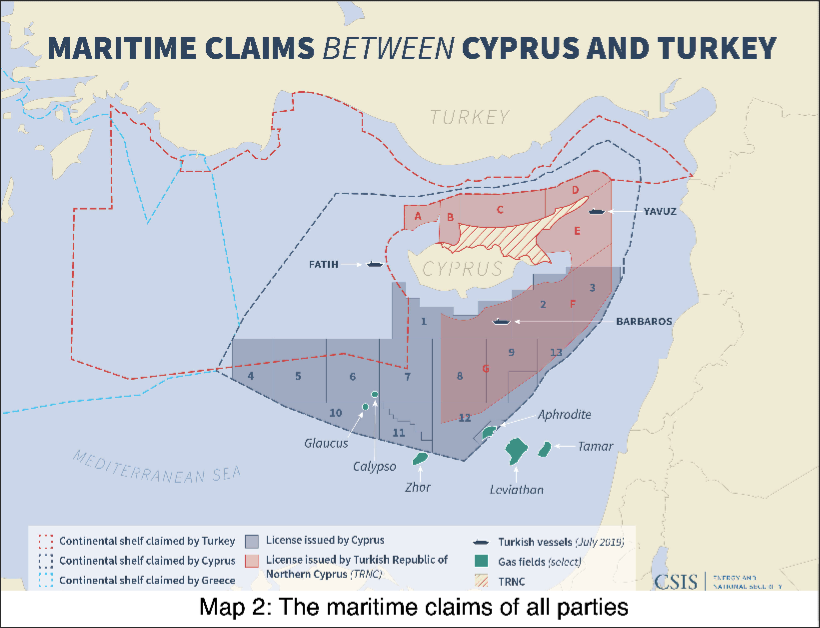

Turkey submitted a note verbaleto the Secretary-General of the United Nations setting out the geographical coordinates of its continental shelf in the Eastern Mediterranean, as established by a delimitation agreement with the “Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus” (“TRNC”). The agreement was signed on 21 September 2011 and ratified by the Turkish government on 29 June 2012. The delimitation agreement outlines some of Turkey’s longstanding positions on the law of the sea. It deals only with the continental shelf and does not provide for the delineation of an exclusive economic zone (EEZ).

While there is nothing precluding coastal states from choosing which maritime zones to claim and/or to delimitate, Turkey’s choice not to delimit an EEZ with the “TRNC” alludes to the Turkish position that islands in certain regions (implying the Aegean Sea) should not be entitled to claim maritime zones of their own other than territorial sea or should have reduced capacity to generate such zones. This stance was formulated in the context of the dispute between Turkey and Greece concerning sovereignty over the maritime space of the Aegean Sea; since the 1970s, Turkey has sustained that the Aegean islands are situated on the continental shelf of Anatolia (Turkey) and, consequently, do not have a continental shelf of their own. This matter was an apple of discord between the Turkish and the Greek delegations over the course of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (‘UNCLOS III’). In the end, by virtue of article 121(2) LOSC, the Conference recognised the rights of islands to generate maritime zones.

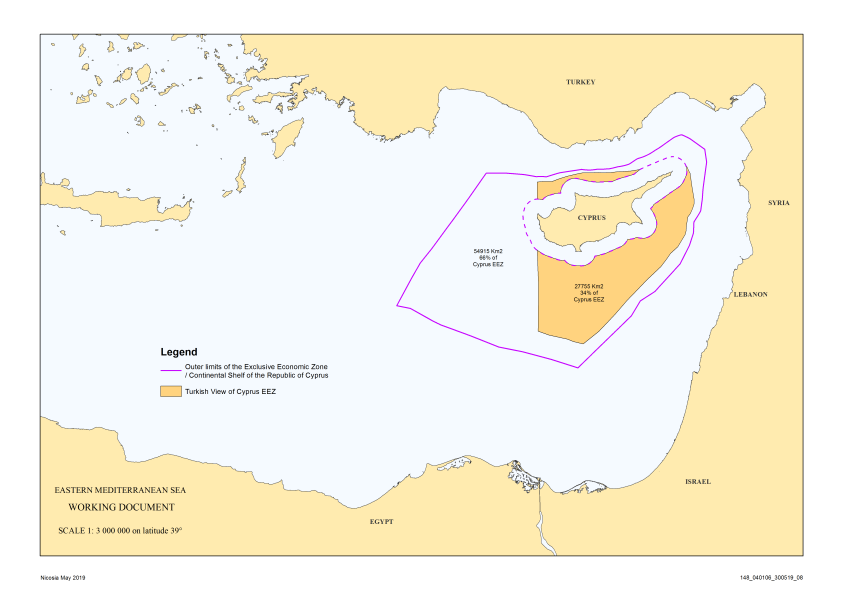

According to its well-established position that islands should not have the capacity to claim extended maritime zones when facing a bigger coastline, Turkey holds the view that Cyprus, being an island, has lesser effect in terms of maritime delimitation than the longer Turkish coastline, which is opposite the northern coast of Cyprus. Hence, as the agreement provides, the continental shelf delineation was carried out in accordance with equitable principles, resulting in a delimitation line closer to Cyprus at some points, which gives Turkey a more extensive maritime space than that allocated to the “TRNC”. Turkey was a fervent advocate of the equitable principles/relevant circumstances method during UNCLOS III, vehemently rejecting the median line/special circumstances method (UNCLOS III, Negotiating Group 7). The “equitable principles” method, which was elaborated in the 1969 Continental Shelf cases, stipulates that all relevant factors should be considered in order to reach an equitable result; however, the Court gave no further guidance as to how such an equitable result would be reached, rendering this method equivocal.

Although the debate over these two delimitation methods was intense, the LOSC did not manage to elucidate the vagueness surrounding the law of maritime delimitation; articles 74 and 83 LOSC merely strike a balance between the two opposing sides’ assertions. Nevertheless, there has been a growing trend towards assimilation of the two methods, early signs of which are discernable in several cases before international tribunals [Anglo-French Continental Shelf Arbitration (para 148), Jan Mayen case (para 56), Qatar v Bahrain case (para 231)]. At the moment, the view supporting the integration of the two methods seems to prevail [International Tribunal on the Law of the Sea (ITLOS) Bangladesh/Myanmar case (para 238)].

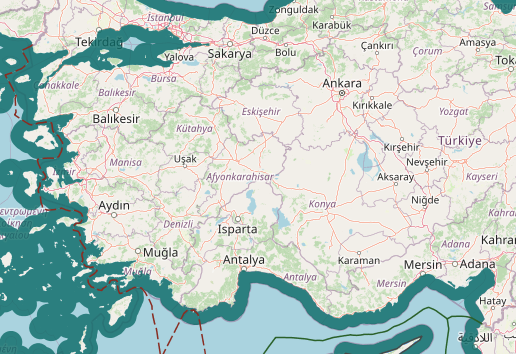

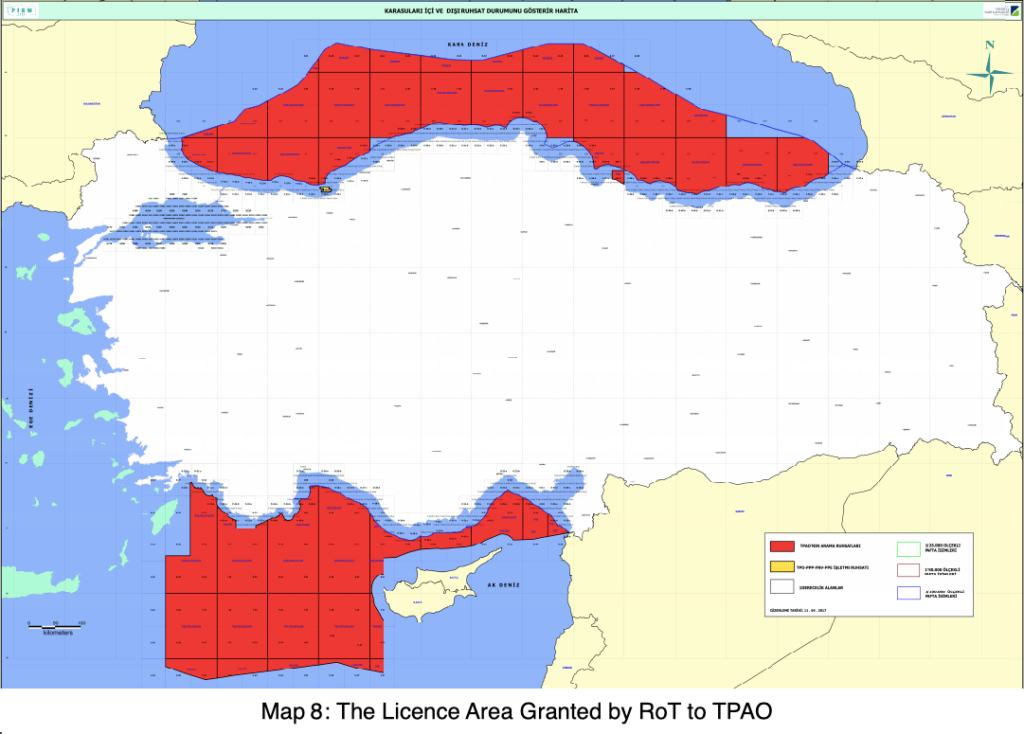

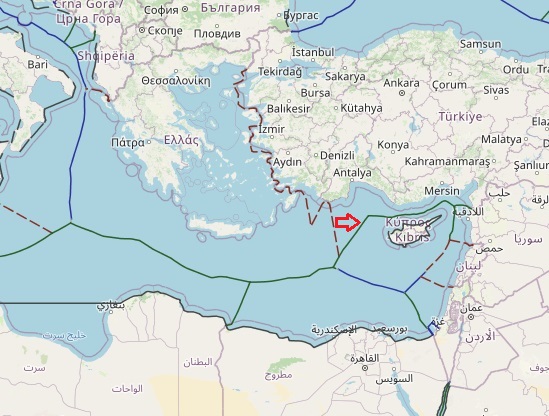

There are huge problems between Republic of Turkey (referred to as “RoT” hereafter) and Republic of Cyprus (referred to as “RoC” hereafter), most of which relates to the law of the sea. While the exploration and exploitation of the hydrocarbon resources around the island of Cyprus is only one of them, it constitutes the most current one. This conflict became a spotlight in the Eastern Mediterranean after the recent developments in the region. In particular unilaterally licensing by RoC the new companies for exploration in the area to which both Cyprus and Turkey have overlapping claims; as well as sending of new exploratory and military vessels by RoT to the region. There are some other serious problems between RoT and RoC, some of which date back to 1960s and arguably constitute the basis of the current problems.

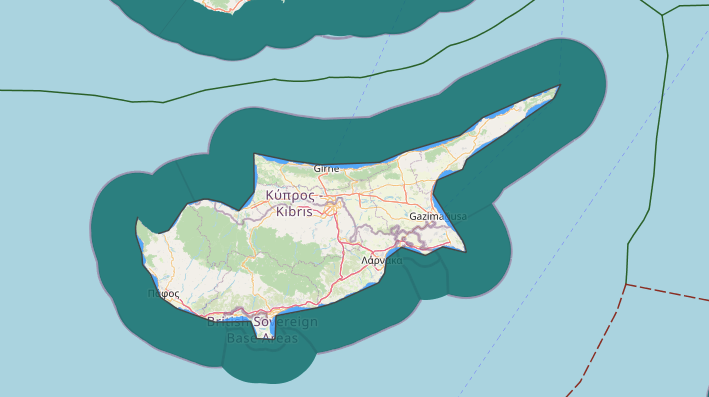

The first historical and the most controversial issue in the island of Cyprus is the status of the non-recognised Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (referred to as “TRNC” hereafter) under international law. This ‘state’ was founded in 1983 by a unilateral independence declaration from RoC. Yet, no state except RoT has officially recognised it. The non-recognition of TRNC by the international community impairs its ‘state’ status under international law. The issue of territorial sovereignty for the northern part of the island is arisen from the arguable status of TRNC. This issue hinders the maritime delimitation and aggravates to ascertain which State’s maritime zone are the waters surrounding Cyprus.

The delimitation of the maritime boundaries between RoT and RoC appears to be another protracted issue. It is mostly dependent to the issue of the status of the TRNC, since the disputes of territorial or maritime sovereignty are the preliminary problems which are pending to be settled in order to reach a final agreement for the maritime zones.5 However, the starting point of the issue of the maritime boundaries is the recently discovered offshore hydrocarbon resources around the island of Cyprus.

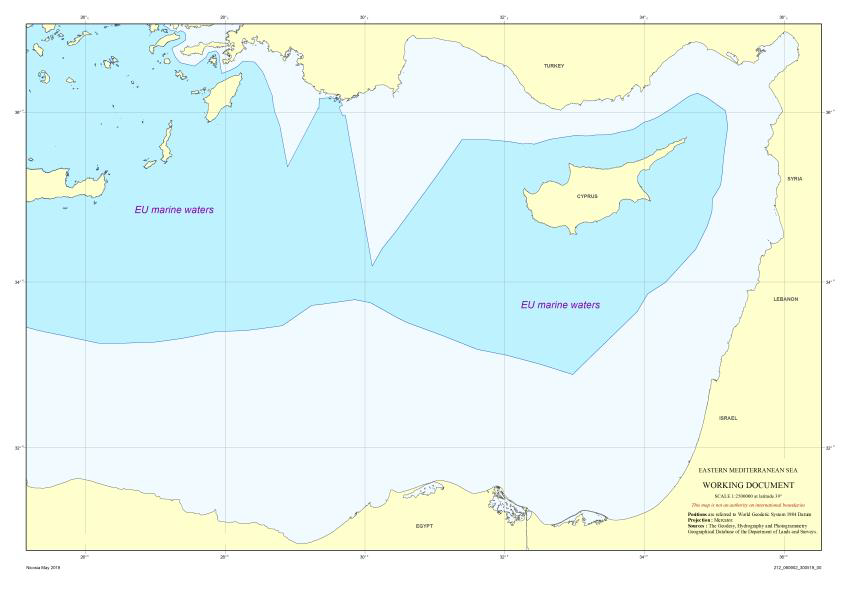

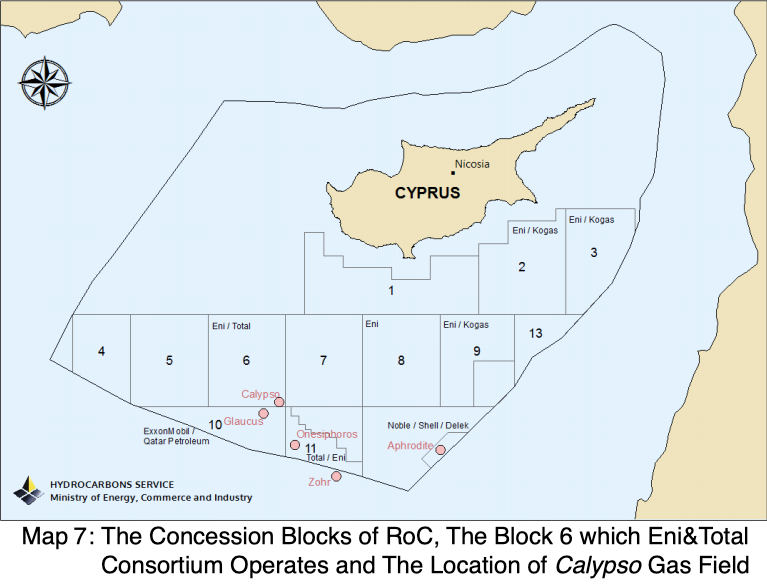

Finally, the issue of exploration and exploitation of the oil and gas resources off Cyprus constitutes another significant issue which aroused all the sovereignty and delimitation problems. Hence, there are 3 interrelated complex problems, all of which have some political and historical roots. There are two reasons why the problems get even more complex. First, there are many parties to the problems. Indeed, two separated nations of the island and their foster-lands in the mainland, namely Greece and RoT, reveals four- directly involved parties to the problems. In addition, the problems are getting intricate and unresolvable because of involvements of the non-regional big actors, such as the USA, France and the European Union (referred to as “EU” hereafter). Second, the recent developments and unilateral moves of the parties exacerbate the dispute.

These three main problems and some additional small ones has leaded to a stretched relationship between RoT and RoC. These problems between RoT and RoC have been subject to academic interrogation by legal scholars, political science experts and professional lawyers. This thesis, a legal research, is to investigate the most current, significant and controversial one of these problems: the hydrocarbons issue. While the other problems, in particular maritime delimitation and sovereignty issues, have strong influences on the hydrocarbons issue, they are only touched upon as long as it seems necessary. Besides, there is another important problem : determination of the applicable legal framework. This is significantly important, since the establishment of the applicable law for this dispute is complicated.

The Republic of Cyprus adopted the Territorial Sea Law in 1964. The law established 12-nautical-mile (22 km; 14 mi) territorial sea. Coordinates of the territorial sea were submitted to the United Nations in 1993 and their validity was reconfirmed in 1996. The continental shelf of Cyprus is defined according to the Continental Shelf Law which was adopted in 1974. After ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) in 1988, Cyprus adopted a new law in 2004, which limited its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) by 12 nautical miles (22 km; 14 mi). The EEZ was delimited by bilateral agreements with Israel, Lebanon and Egypt. Cyprus has called on Turkey to delineate the sea boundaries between the two countries.