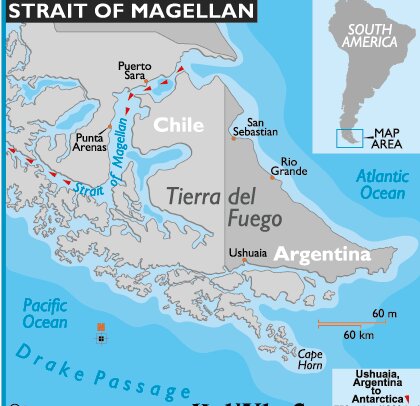

The 310-mile-long Strait of Magellan connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans

at the southern tip of South America. Navigation through the Strait of Magellan

is governed by article V of the 1881 Boundary Treaty between Argentina

and Chile, which states that the Straits are neutralized forever, and free navigation

is assured to the flags of all nations. Article 10 of the 1984 Treaty of

Peace and Friendship between Argentina and Chile reaffirms that status: “the

delimitation agreed upon herein, in no way effects the provisions of the Boundary

Treaty of 1881, according to which the Straits of Magellan are perpetually

neutralized and freedom of navigation is assured to ships of all flags . . .” In concluding that the Strait of Magellan therefore falls under the article 35(c) exception of the LOS Convention, the Department of State advised American

Embassy Santiago, Chile, that:

This long.standing guarantee of free navigation for all vessels [in the 1881 Treaty]

has been amply reinforced by practice, including practice recognizing the right

of aircraft to overfly. . . . Essentially, the USG position would be that the 1881

Treaty and over a century of practice have imbued the Strait of Magellan with a

unique regime of free navigation, including a right of overflight. That regime has

been specifically recognized and reaffirmed by both Argentina and Chile in the

Beagle Channel Treaty. Hence, the United States and other States may continue

to exercise navigational and overflight rights and freedoms in accordance with this

long.standing practice.

In depositing its instrument of ratification of the LOS Convention on December

1, 1995, Argentina stated, inter alia:

(b) With regard to Part III of the Convention, the Argentine Government declares

that in the Treaty of Peace and Friendship signed with the Republic of Chile on

29 November 1984, which entered into force on 2 May 1985 and was registered

with the United Nations Secretariat in accordance with Article 102 of the Charter

of the United Nations, both States reaffirmed the validity of article V of the

Boundary Treaty of 1881 whereby the Strait of Magellan (Estrecho de Magallanes)

is neutralized forever with free navigation assured for the flags of all nations. The

aforementioned Treaty of Peace and friendship also contains specific provisions

and a special annex on navigation which includes regulations for vessels flying the

flags of third countries in the Beagle Channel and other straits and channels of

the Tierra del Fuego archipelago.

On September 6, 1996, Chile replied inter alia as follows:

In the view of the Chilean government, this declaration is inaccurate in its formulation

and does not reflect the wording of the relevant provision of the treaties

in question.

Article 10, paragraph 4, of the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship does, in

fact, provide that the boundary agreed upon in respect of the eastern end of the

Strait of Magellan in no way alters the provisions of the 1881 Boundary Treaty,

whereby the Strait of Magellan is neutralized forever with free navigation assured

for the flags of all nations under the terms laid down in it article V.

However, as regard the reference to provisions on navigation, it should be noted

that article 13, paragraphs 1 and 2, of the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship,

under the chapter Economic cooperation and physical integration, expressly

states that:

The Republic of Chile, in exercise of its sovereign rights, shall grant to the

Argentine Republic the navigation facilities specified in articles 1 to 9 of annex II.

The Republic of Chile declares that ships flying the flag of third countries may

navigate without obstacles over the routes indicted in articles 1 and 8 of annex II,

subject to the pertinent Chilean regulations.

Moreover, article 1, paragraphs 1 and 2, of annex II (concerning navigation) of

the 1984 Treaty of Peace and friendship adds:

For maritime traffic between the Strait of Magellan and Argentine ports in the

Beagle Channel and vice versa, through Chilean internal waters, Argentine vessels

shall enjoy navigation facilities exclusively along the following route:

Canal Magdalena, Canal Cockburn, Paso Brecknock or Canal Ocasión, Canal

Ballenero, Canal O’Brien, Paso Timbales, north-west arm of the Beagle Channel

and the Beagle Channel as far as the meridian of 68°36’38.5” West longitude and

vice versa.

The above-cited provision unmistakably demonstrate that the navigation facilities

which the Republic of Chile, in exercise of its sovereign rights, grants to the

Argentine Republic and to ships flying the flag of third countries are through

Chilean internal water, by a route described in the Treaty; together with the other

features and modalities laid down in annex II these are essential aspects of the

navigation regime established by the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship and

the omission thereof from the Argentine declaration may be misleading as to the

nature of these waters.

For the same reason, it is inappropriate for the Argentine declaration to refer

to the above-mentioned navigation facilities in connection with Part III of the

Convention, “Straits used for international navigation,” since the area in question

has always consisted of Chilean internal waters and not international straits.

Lastly, nowhere does the 1881 Boundary Treaty or the 1984 Treaty of Peace

and Friendship make a generic reference to a so-called “Tierra del Fuego archipelago;”

it is therefore inappropriate for the Argentine declaration to mention in

the context of the above-named treaties.

In response to the UN Secretary-General’s February 21, 1996 request for copies

of any Argentine laws and regulations relating to international straits, Argentina

forwarded copies of the 1881 and 1984 treaties and added:

Article 5 of the 1881 Treaty and article 10 of the 1984 Treaty establish neutrality

and the freedom of ships of all flags to navigate through the Strait of Magellan.

Annex II to the 1984 Treaty establishes the navigation regime between the Strait

of Magellan and Argentine ports in the Beagle Channel and vice versa, as well as

the navigation regime along the Strait of Maire.

On September 6, 1996, Chile responded, as follows:

(a) Under article 35(c) of the Convention on the Law of the Sea, nothing in

Part III affects the legal regime in straits in which passage is regulated in whole or in part by long-standing international conventions in force specifically relating

to such straits. As this is precisely the case of the Strait of Magellan, the

provisions of Part III do not apply to it;

(b) Argentina does not border the Strait of Magellan. Under the 1881 Boundary

Treaty, the whole of the Strait of Magellan – including, of course, the land

bordering it on both sides – is under Chilean sovereignty. Therefore, it is not

incumbent on Argentina to give publicity to laws and regulations on straits

which are not under its sovereignty;

(c) Lastly, with regard to annex II to the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship,

which establishes the regime for navigation between the Strait of Magellan and

Argentine ports in the Beagle Channel and vice versa, the statements in the

foregoing paragraphs on the clear provisions regulating such navigation should

be borne in mind.

Unquestionably, the strait consists mainly of Chilean internal waters.

Therefore, it is not a strait used for international navigation, and it is inappropriate

for Argentina to invoke article 42(3) in referring to the provisions of the

1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship in this regard.

Since the issues raised in the present communication must have a clear interpretation

both for the parties and for third countries, the Permanent Mission of

Chile to the United Nations hereby requests the Secretary-General, through the

Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea, Office of Legal Affairs, to give

due publicity to the present document . . .

On May 14, 1997, Argentina replied:

. . . it should be pointed out that, in ratifying that international convention, which,

as the Government of Chile is well aware, was done subsequent to the entry into

force of the Treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1984, the Argentine Republic

irrefutably expressed its desire to maintain the full validity of all the provisions of

the treaty of Peace and Friendship of 1984; thus, the application of the United

Nations Convention

on the Law of the Sea does not affect the legal regime of the

above-mentioned bilateral treaty between Argentina and Chile.

Accordingly, the fact that the reference to the Strait of Magellan is followed by

a reference to the existence of the navigation regime of the 1984 Treaty implies an

express reaffirmation of article V of the 1881 Boundary Treaty and, in addition, of

the full validity of the norms contained in annex 2 of the 1984 Treaty, including

the legal status of the waters used for navigation.

These treaties contain regulations which affect third States. The Argentine presentation

was for information purposes and did not put forward any interpretation

of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, the 1881 Boundary

Treaty, the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship or any other aspects of the

issue.

As a party to the 1881 Boundary Treaty, the Argentine Republic has the power

to refer to it in any documents it deems relevant. In this case, such power is even

more obvious since that international instrument embodies a longstanding regime

as recognized by article 35(c) of the United Nations Convention on the Law of

the Sea. Therefore, it cannot be considered as being outside the legal framework

of the Convention.

Moreover, article V of the 1881 Boundary Treaty, whereby the Strait of Magellan

is neutralized forever with free navigation assured for the flags of all nations,

creates obligations and rights both of the Argentine Republic and the for the

Republic of Chile. Therefore, both parties should ensure effective compliance with

its provisions.

In addition, Article 10 of the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship – which, as

noted above, replicates article V of the 1881 treaty – stipulates the obligation of the

Argentine Republic to maintain, at any time and in whatever circumstances, the

right of ships of all flags to navigate expeditiously and without obstacles through

its jurisdictional waters to and from the Strait of Magellan.

Consequently, Argentina, as a State Party, together with Chile, of the 1881

Boundary Treaty and the only one of the two which has become a party to the

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, has the power to give due

publicity, in ratifying that Convention, to the legal regime for the area of the

Strait of Magellan.

In view of the foregoing, there can be no doubt about the juridical grounds supporting

the [Argentine] interpretative declaration and its note verbale of 15 April 1996 As mentioned above, a different scope and intention are being attributed to the instruments issued by the Argentine Republic than what is clearly evident in

their texts and legal context.

The Argentine Republic cannot agree with other statements made by the Government

of Chile in the above-mentioned notes. Among other things, it does

not agree that the waters in the south of the Strait of Magellan have always been

Chilean internal waters and not international straits. The Argentine Republic did

not consider them as such until the 1984 Treaty of Peace and Friendship, which,

as noted above, established a regime for navigation through the waters described

in its annex 2.

In relation to the foregoing, it must be stressed that the norms codified in paragraph

2, article 8; paragraph 1, article 3; and subparagraph

(a), article 35, of the

United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea are also relevant aspects.

Moreover, the Argentine Republic does not share the interpretation concerning

the inapplicability of Part III of the United Nations Convention on the Law

of the Sea, since such interpretation does not follow from article 35(c) of the

Convention. That norm, in fact, establishes that the provisions of part III do not

affect the legal regime in straits in which passage is regulated in whole or in part

by long-standing international conventions in force.

Without prejudice to the above, it is not the purpose of the Argentine Republic

to embark on a discussion of abstract topics or situations. . . .