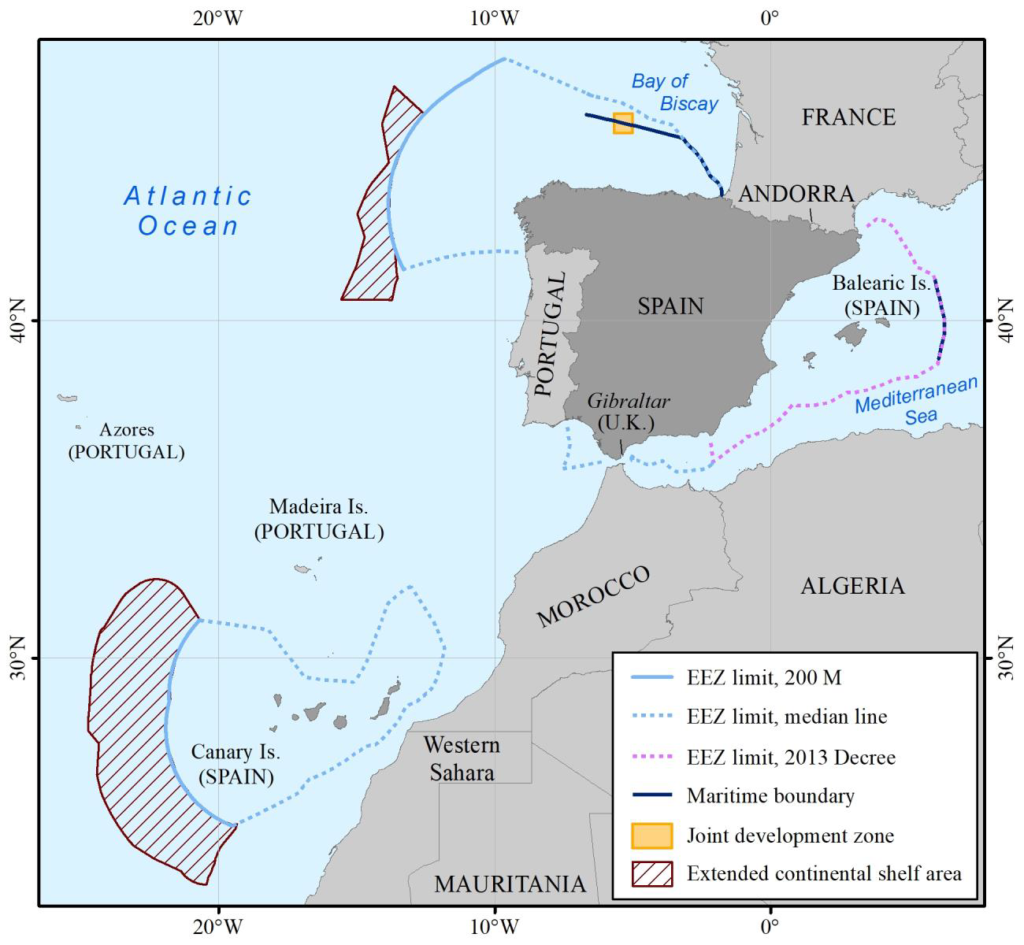

the list of geographical coordinates of points for the drawing of the limits of the Fisheries Protection Zone in the Mediterranean Sea in 2000 and a list of geographical coordinates of points concerning the outer limits of its exclusive economic zone in 2018.

Fishing zones

In the Mediterranean, there are four countries, namely, Algeria, Malta, Spain and Tunisia that have claimed fishing zones extending beyond their territorial waters.

In 1994, Algeria claimed an exclusive fishing zone (zone de pêche réservée), beyond its territorial sea and adjacent to it, whose extent 32 nautical miles from the western maritime border and Ras Ténés and, 52 nautical miles from Ras Ténés to the eastern maritime border.

Malta has claimed a 25-mile exclusive fishing zone since 1978. However, because of the geographical features of the area, the northern boundary of the Maltese fishing zone falls short of 25 nautical miles.

In 1951, Tunisia claimed an exclusive fishing zone that is delimited for about half of its length by the 50-m isobath. Use of this criterion to delimit a maritime zone is unique in international practice. Because of the shallow waters in the region, the external limit of this fishing zone is a line the points of which are located, in certain cases, as far away as 75 nautical miles from the Tunisian coast and only 15 nautical miles from the Italian island of Lampedusa. The Tunisian fishing zone encompasses the rich bank called Il Mammellone (“the Big Breast”), which has traditionally been exploited by Italian fishermen and is considered as an area of the high seas by Italy.

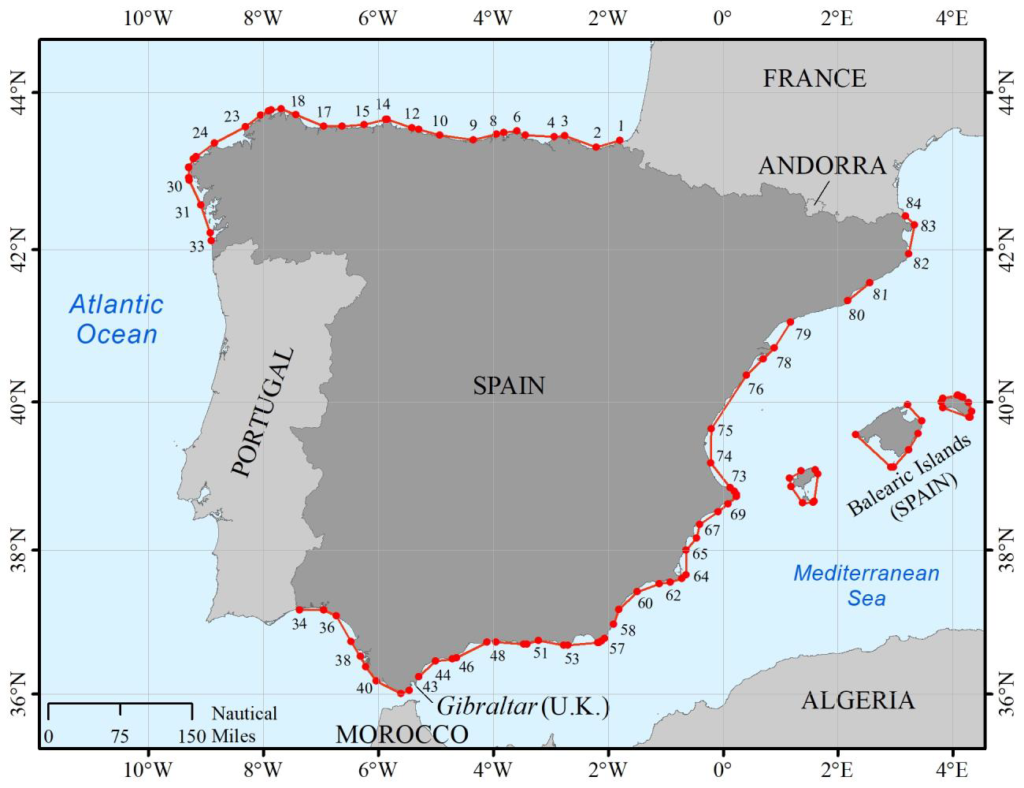

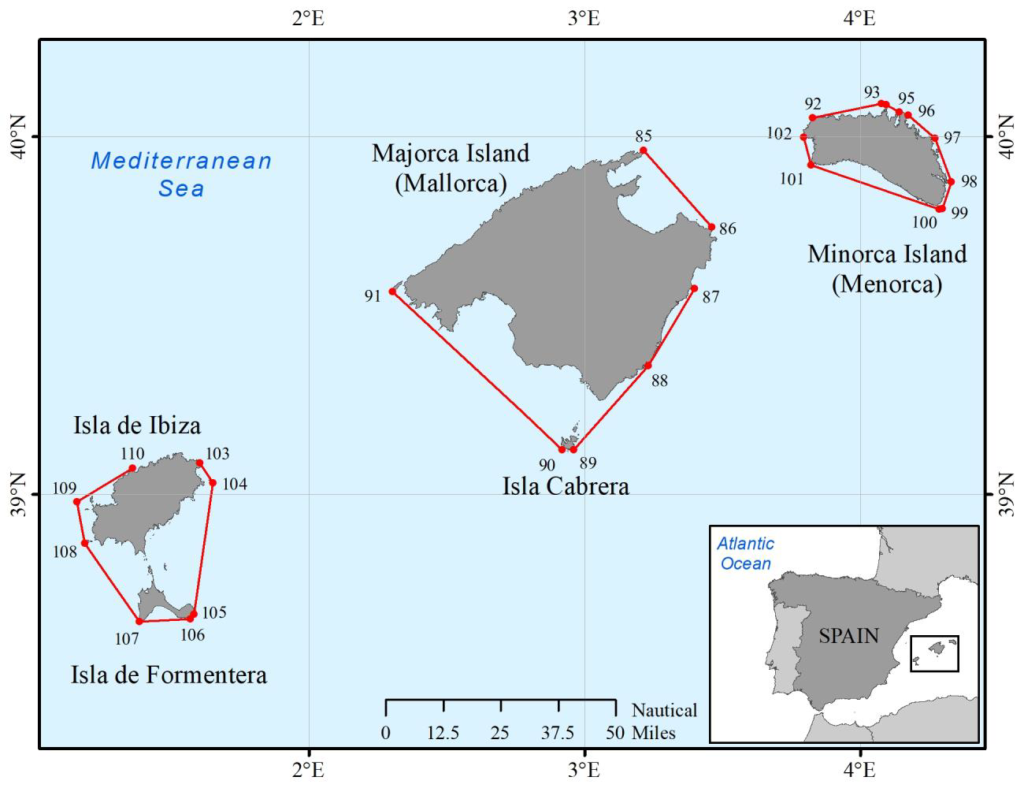

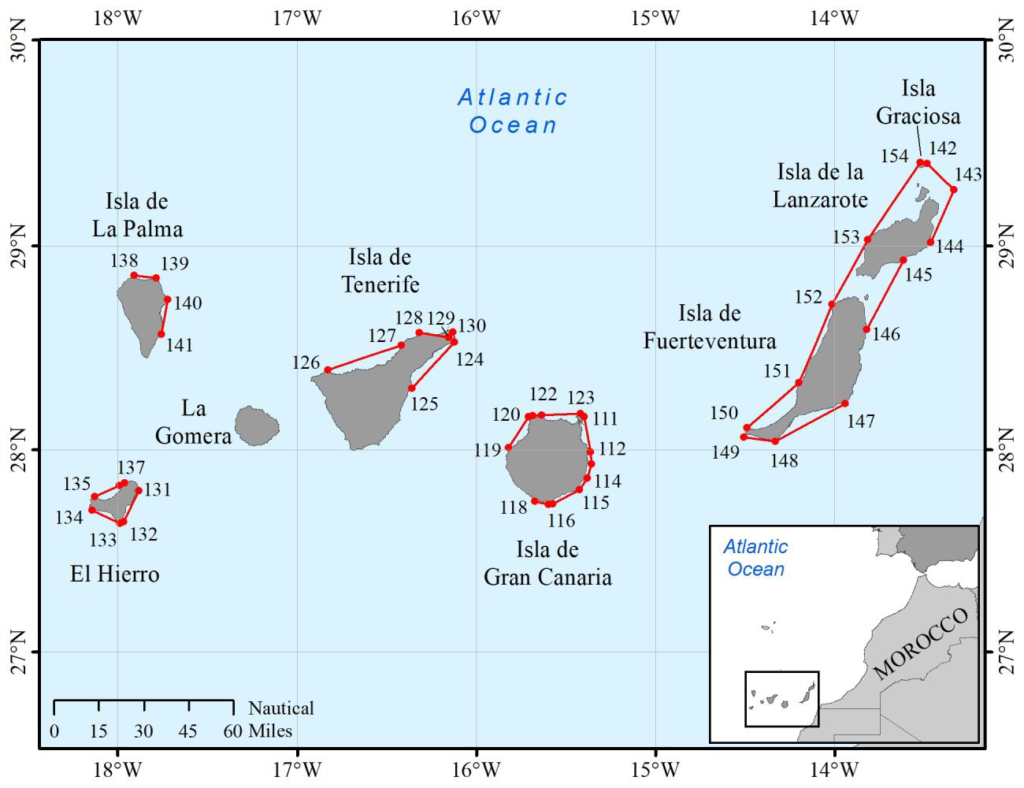

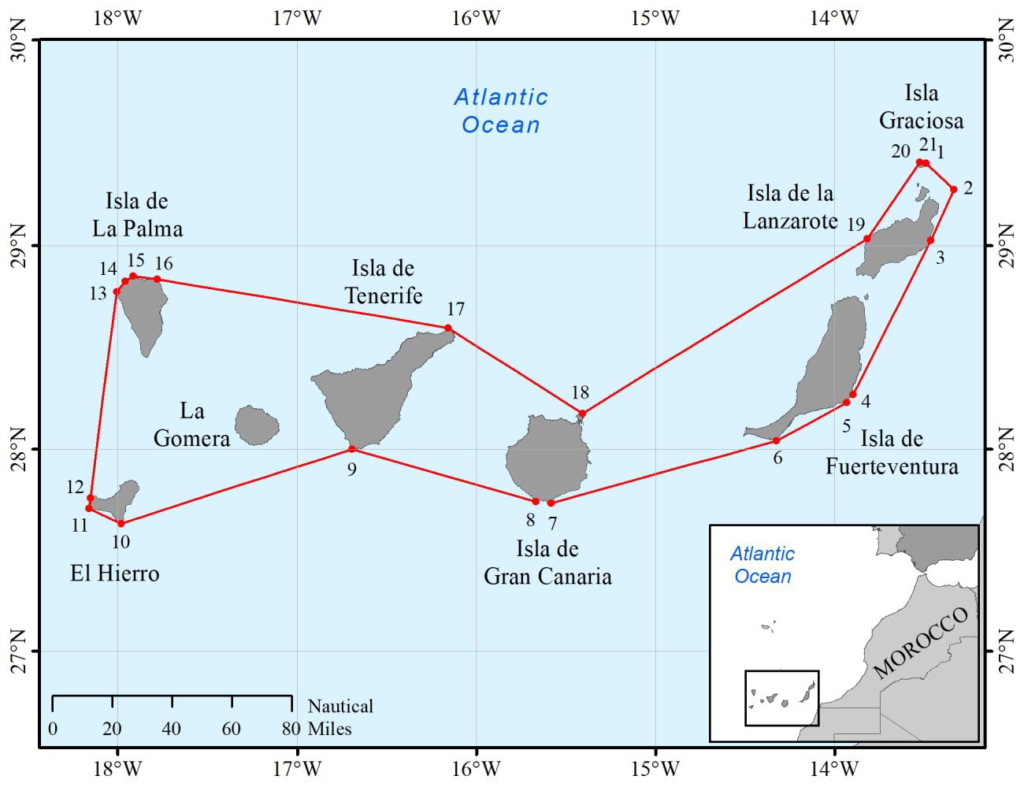

More recently, Spain, by Royal Decree No. 1315/1997 of 1 August 1997 as modified, claimed a 37-mile wide fisheries protection zone measured from the outer limit of the territorial sea. The fisheries protection zone is delimited according to the line which is equidistant (median line) from the opposite coast of Algeria and Italy and the adjacent coast of France. No fisheries protection zone is established in the Alboran Sea, off the Spanish coast facing Morocco. Interestingly, it was argued, in the preamble of the Royal Decree, that extension of jurisdiction over fisheries resources beyond territorial waters was a necessary step to ensure adequate and effective protection of fisheries resources. In Spain’s view, maintenance of the status quo, which was already characterized by excessive exploitation of fisheries resources, was unacceptable as it would have rapidly led to the depletion of these resources.

Building on the Spanish approach, the European Union, in a 2002 document laying down a Community Action Plan for the conservation and sustainable exploitation of fisheries resources in the Mediterranean, advocated the declaration of fisheries protection zones, of up to 200 nautical miles, to improve fisheries management in the Mediterranean. It stressed the fact that establishment of fisheries protection zones would facilitate control and contribute significantly to fighting against illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing. The document emphasized the need to build a consensus through wide consultation and involvement of all countries bordering the Mediterranean basin, if such undertaking is to be successful and effective. To achieve this, a common approach should first be agreed upon by Community Member States and, subsequently, by all the countries in the region. Recently, France indicated that it adhered to this approach and that the legislation to declare a 50-mile fisheries protection zone off its Mediterranean coast was in the process of being drafted.

While declaration of fisheries protection zones will have legal implications on jurisdiction over fisheries resources, it will not affect jurisdiction over inter alia mineral or fossil resources, navigation or any other rights in this area. Unlike sovereign rights conferred upon the coastal State in the EEZ, those enjoyed by it in a fishing zone are restricted to the exploration, exploitation, management and conservation of fisheries resources. The effect of establishing fisheries protection zones will be to reduce the area of high seas and thus to modify access rights to certain fisheries. Loss of access to fishing grounds that were previously part of the high seas could be overcome through the conclusion of bilateral fisheries access agreements. In areas where extension of national jurisdiction may have serious detrimental social and economic effect, mitigating measures may be worked out through, for instance, recognition of historical fishing rights for specified vessels. Should the approach be successful, extension of national jurisdiction over fisheries is likely to translate into most of the resources being under national jurisdiction, with possible impact on the mandate of the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean.