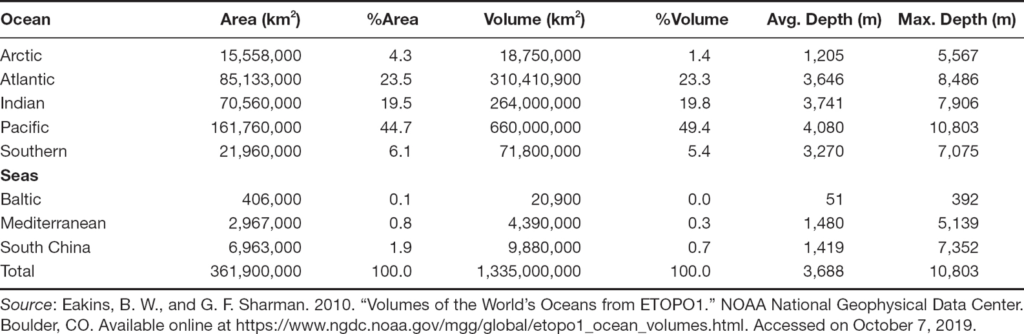

Scientists now recognize five bodies of water as oceans today: Pacific, Atlantic, Indian, Arctic, and Southern (also called the Antarctic). Depending on the authority, seven oceans may be identified, with the Pacific divided into the North and South Pacific and the Atlantic into the North and South Atlantic. Table 1.1 summarizes some major properties of the five oceans.

Note that this table also contains data for three bodies of water called seas. The world’s system of oceans is complex, consisting of several smaller bodies of water known as bays, bights, channels, covers, estuaries, fjords, gulfs, passages, seas, sounds, and straits. These bodies of water are usually indentations off one or another ocean. As a group, they are often referred to as marginal seas. Each term has a distinct (but not always agreed upon) definition based on its general shape and manner of formation (“Examples of Landforms” 2019; “Marginal Seas of the World” 2019).

Ocean Currents

In spite of these designations, the world’s oceans can also be thought of as a single body of water through which currents flow at and below the surface. This pattern of water flow is known as thermohaline circulation. The formal name comes from the two elements responsible for the flow: heat (thermo-) and salt (-haline). The system is also known informally as the ocean conveyor belt, great ocean conveyor, or global conveyor belt. A more precise, but not entirely synonymous, term for the phenomenon is meridional overturning circulation (MOC). (For an image and video of the thermohaline circulation, see “Thermohaline Circulation” 2016 and Shirah 2009, respectively. For a detailed description of the thermohaline system, see Van Aken 2007. For an animation of the MOC at the surface and subsurface levels, see “Meridional Overturning Circulation [MOC]” 2015.)

The thermohaline/MOC system consists of two major processes. In one process, water that has been cooled and has higher salinity tends to sink to the ocean bottom. In the other process, water that has been warmed and has less density rises to the ocean’s surface. The first of these processes occurs around Antarctica and in the North Atlantic and North Pacific. In these regions, cooler, denser water tends to sink and flow in northerly and southerly directions, respectively, to warmer parts of the planet. These currents tend to be slow and flow along the lowest regions of the oceans, its basins. As the flow continues out of colder regions, it becomes warmer, rising to the ocean’s surface. In this part of the MOC, water flow occurs closer to the ocean’s surface and at a greater rate of speed. These surface currents are readily observed, well studied, and generally understood. One of the most familiar of these surface currents is the Gulf Stream, which lies off the eastern coast of North and Central America. Nearly two dozen other major surface currents exist in other parts of the world (“Currents” n.d.).

surface. In this part of the MOC, water flow occurs closer to the ocean’s surface and at a greater rate of speed. These surface currents are readily observed, well studied, and generally understood. One of the most familiar of these surface currents is the Gulf Stream, which lies off the eastern coast of North and Central America. Nearly two dozen other major surface currents exist in other parts of the world (“Currents” n.d.).

The mechanisms of surface and subsurface current flows are quite different. The former are affected by factors other than density and salinity of water, such as winds and geographic features. They may travel anywhere from a few to more than 100 kilometers per day. Subsurface currents are driven almost exclusively by density and salinity. They move much more slowly than surface currents and may take as long as 1,000 years to complete a single cycle of the thermohaline circuit (Pidwimy and Jones 2018).

Ocean Features

Earth’s oceans occupy geological structures known as ocean basins. An ocean basin is simply a bowl-shaped depression in Earth’s crust filled with seawater. Ocean basins may vary in size from less than 20,000 square kilometers in area (the Marmara Sea in Turkey) to nearly 162 million square kilometers (the Pacific Ocean) (table 1.1; “5 Smallest Seas on Earth” 2018). Most ocean basins contain several characteristic features, such as continental shelves and slopes, submarine canyons, mid-ocean ridges, abyssal plains, seamounts and guyots, trenches, and volcanic islands. (Follow this discussion with the visual at “Ocean Floor” 2019.)