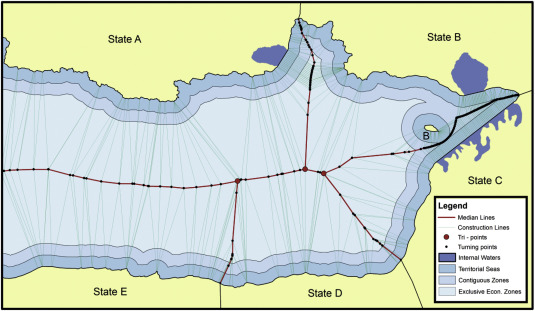

In theory, the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone could follow a different line than the continental shelf. For practical reasons, however, states seem to have wanted to have their maritime zones delimited by a single maritime boundary for all purposes. The reason for this lies first of all in the shared overlap of natural resources between the two zones.

View More what is the meaning of single maritime boundaries line (single line with dual purpose or all-purpose line)Month: August 2021

Three-stage Approach of Maritime Delimitation in law of the sea (customary international law and court decisions)

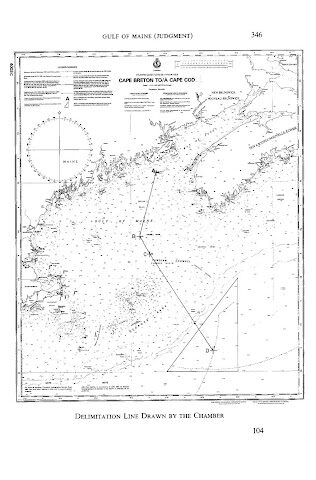

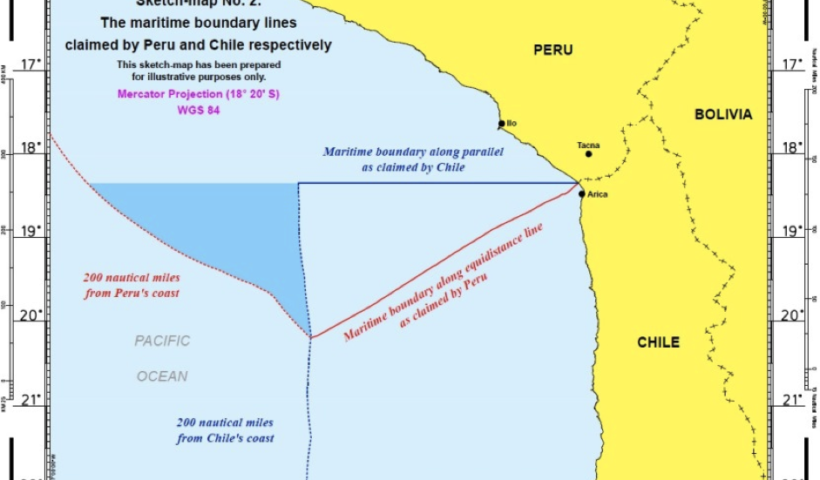

Three-stage Approach of Maritime Delimitation that the International Court of Justice (ICJ) “has developed a settled jurisprudence relating to the interpretation of those provisions”, while quoting the Court’s description of the three-stage approach of first drawing a provisional delimitation line, then assessing that line in the light of the relevant circumstances of the case and finally applying the disproportionality test to determine whether the proposed boundary results in an equitable solution, which has been developed in the context of the delimitation of the continental shelf and the exclusive economic zone. “international law thus calls for the application of an equidistance line, unless another line is required by special circumstances”. However, the assertion that the ICJ’s three-stage approach is settled jurisprudence in relation to article 15 is not borne out by a reading of the judgments. The quotation in paragraph 999 of the Award is from the judgment of the Court in Peru v. Chile. As the Award indicates, the Court in this connection makes reference to its earlier decisions in Black Sea and Territorial and Maritime Dispute (Nicaragua v. Colombia). All three decisions discuss the three-stage approach in relation to the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf and there is nothing in these judgments suggesting that the Court considered that the three-stage approach applies equally to the delimitation of the territorial sea under article 15 of the Convention.

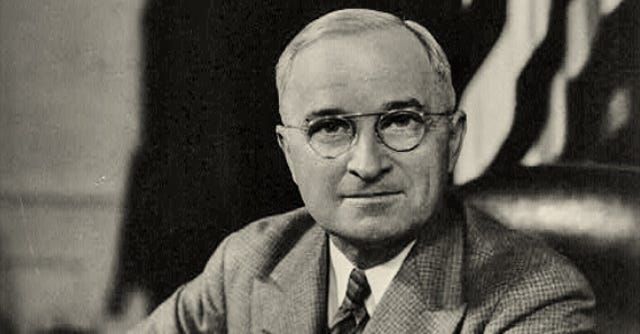

View More Three-stage Approach of Maritime Delimitation in law of the sea (customary international law and court decisions)The Truman Proclamation, 1945 (Proclamation 2667—Policy of the United States With Respect to the Natural Resources of the Subsoil and Sea Bed of the Continental Shelf)

U.S. President Harry S. Truman’s executive order on September 28, 1945, proclaiming that the resources on the continental shelf contiguous to the United States belonged to the United States. This was a radical departure from the existing approach, under which the two basic principles of the law of the sea had been a narrow strip of coastal waters under the exclusive sovereignty of the coastal state and an unregulated area beyond that known as the high seas. The speed at which Truman’s continental shelf concept was recognized through emulation or acquiescence led Sir Hersch Lauterpacht to declare in 1950 that it represented virtually “instant custom.”

View More The Truman Proclamation, 1945 (Proclamation 2667—Policy of the United States With Respect to the Natural Resources of the Subsoil and Sea Bed of the Continental Shelf)what is the meaning of Special Circumstances and Relevant Circumstances in delimitation process at law of the sea

Special circumstances are those circumstances which might modify the results produced by an unqualified application of the equidistance principles. Small islands and maritime features are arguably the archetypical special circumstances as much in the delimitation of the territorial sea as in the delimitation of the continental shelf/EEZ. The Court has recognized in numerous cases, including the North Sea Continental Shelf, Tunisia/Libya, Libya/Malta and Qatar v. Bahrain cases that the equitableness of an equidistance line depends on whether the precaution is taken of eliminating the disproportionate effect of certain islets, rocks and minor coastal projections.

View More what is the meaning of Special Circumstances and Relevant Circumstances in delimitation process at law of the seaequitable result in maritime delimitation and most acceptable law for delimitation process

The notion of equity is at the heart of the delimitation of the CS(continental shelf) and entered into the delimitation process with the 1945 proclamation of US President Truman, concerning the delimitation of the CS between the Unites States and adjacent States. The Truman proclamation inspired the Court during the 1969 North Sea case, when the Court stated that “delimitation is to be effected by agreement in accordance with equitable principles, and taking into account all the relevant circumstances.” This idea became doctrine and was reiterated and confirmed by the ICJ and arbitral tribunals in subsequent cases. Articles 74 and 83 of the 1982 LOS Convention concerning the delimitation of the EEZ and the CS provides for effecting the delimitation by agreement, in accordance with international law and in order to achieve an equitable result.

View More equitable result in maritime delimitation and most acceptable law for delimitation processDelimitation of the Maritime Boundaries between the adjacent States

Delimitation of the Maritime Boundaries between the adjacent Boundaries between the adjacent States , a PDF+PPT lecture by Nugzar Dundua, United Nations United Nations, The…

View More Delimitation of the Maritime Boundaries between the adjacent StatesOverlapping claims to territorial sea in law of the sea and LOSC

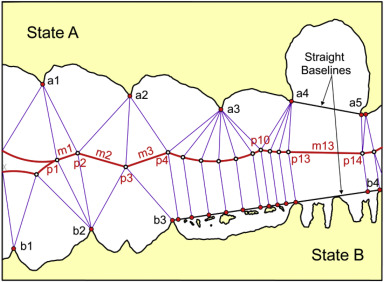

Delimitation of the territorial sea between States with opposite or adjacent coasts

Where the coasts of two States are opposite or adjacent to each other, neither of the two States is entitled, failing agreement between them to the contrary, to extend its territorial sea beyond the median line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points on the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial seas of each of the two States is measured. The above provision does not apply, however, where it is necessary by reason of historic title or other special circumstances to delimit the territorial seas of the two States in a way which is at variance therewith.

This provision in a near-verbatim reproduction of the equivalent provision of the 1958 Territorial Sea Convention. It reflects a compromise reached at UNCLOS I – and again at UNCLOS III – between two general proposed methods of delimitation.

Overlapping claims to internal waters in law of the sea and LOSC

Several adjacent coastal States have designated straight territorial sea baselines in a manner that generates overlapping claims to internal waters. The LOSC contains only limited references to internal waters, none of which concern delimitation or OCA management. The absence of detailed provisions in this context flows from the characterization of internal waters under customary law: Such waters appertain to the land territory of a coastal State and are subject, with limited exception, to full territorial sovereignty. The absence in the law of the sea of detailed rules concerning internal waters is a deliberate deference to the territorial rights of coastal States.

View More Overlapping claims to internal waters in law of the sea and LOSCMare Liberum

Mare Liberum (or The Freedom of the Seas) is a book in Latin on international law written by the Dutch jurist and philosopher Hugo Grotius, first published in 1609. In The Free Sea, Grotius formulated the new principle that the sea was international territory and all nations were free to use it for seafaring trade. The disputation was directed towards the Portuguese Mare clausum policy and their claim of monopoly on the East Indian Trade. Grotius wrote the treatise while being a counsel to the Dutch East India Company over the seizing of the Santa Catarina Portuguese carrack issue. The work was assigned to Grotius by the Zeeland Chamber of the Dutch East India Company in 1608.

View More Mare LiberumUnited Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and its implementing agreements in sustainable development

On 3 February 2014, on the margins of the eighth session of the Open Working Group on Sustainable Development Goals, the Division for Ocean Affairs…

View More United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and its implementing agreements in sustainable developmentThe UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, A HISTORICAL BACKGROUND

By the mid-1950s, it had become increasingly clear that existing international principles governing ocean

affairs were no longer capable of effectively guiding conduct on and use of the seas. The oceans had long been

subject to the freedom-of-the-sea doctrine — a seventeenth century principle that limited national rights and

jurisdiction over the oceans to a narrow belt of sea surrounding a nation’s coastline. The remainder of the seas

was proclaimed to be free to all and belonging to none.

But technological innovations, coupled with a global population explosion, had drastically changed man’s

relationship to the oceans. Larger and more advanced fishing fleets were endangering the sustainability of fish

stocks, the marine environment was increasingly threatened by pollution caused by industrial and other human

activity, and tensions between States over conflicting claims to the oceans and its vast resources were intensifying.

In this atmosphere, the United Nations convened the first of three conferences on the Law of the Sea in

Geneva in 1958. The conference produced four conventions, dealing respectively with the territorial sea and

the contiguous zone, the high seas, fishing and conservation of the living resources of the high seas, and the

continental shelf.

Two years later, the United Nations convened the Second Conference on the Law of the Sea, which, in spite

of intensive efforts, failed to produce an agreement on the breadth of the territorial sea and on fishing zones.

While the first two Conferences on the Law of the Sea had advanced a number of issues concerning international ocean affairs, the majority still remained unsolved. The creation of a comprehensive international

treaty was to become the legacy of the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea.

A speech to the United Nations General Assembly by Malta’s Ambassador to the United Nations, Arvid

Pardo, on 1 November 1967, has often been credited with setting in motion a process that spanned 15 years and

culminated with the adoption of the Convention on the Law of the Sea in 1982. In his speech, Ambassador

Pardo urged the international community to take immediate action to prevent the breakdown of law and order

on the oceans, a disaster that many feared loomed on the horizon. He called for “an effective international

regime over the seabed and the ocean floor beyond a clearly defined national jurisdiction”.

Ambassador Pardo’s call to action came at the right time. In the next five years, the international community took several major steps that were crucial in setting the stage for a comprehensive treaty. In 1968, the

General Assembly established a Committee on the Peaceful Uses of the Seabed and the Ocean Floor beyond the

Limits of National Jurisdiction, which began work on a statement of legal principles to govern the uses of the

seabed and its resources. In 1970, the Assembly unanimously adopted the Committee’s Declaration of

Principles, which declared the seabed and ocean floor beyond the limits of national jurisdiction to be the common heritage of mankind. The same year, the Assembly decided to convene the Third Conference on the Law

of the Sea to create a single comprehensive international treaty that would govern all ocean affairs.

Third Conference on the Law of the Sea

The Third Conference on the Law of the Sea opened in 1973 with a brief organizational session, followed in 1974

by a second session held in Caracas, Venezuela. In Caracas, delegates announced that they would approach the

new treaty as a “package deal”, to be accepted as a whole in all its parts without reservation on any aspect. This

decision proved to be instrumental to the successful conclusion of the treaty.

A first draft was submitted to delegates in 1975. Over the next seven years, the text underwent several

major revisions. But on 30 April 1982, an agreement had been reached and the final text of the new convention

was put to a vote. The vote, which took place at United Nations Headquarters in New York, marked the end of over a

decade of intense and often strenuous negotiations, involving the participation of more than 160 countries from all

regions of the world and all legal and political systems.

The Convention was adopted with 130 States voting in favour, 4 against and 17 abstaining. Later that same year,

on 10 December, the Convention was opened for signature at Montego Bay, Jamaica, and received a record number of

signatures — 119 — on the first day.

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea entered into force on 16 November 1994, one year after it

had reached the 60 ratifications necessary. Today the Convention is fast approaching universal participation, with 138

States, including the European Union, having become parties.

The Convention is supplemented by two agreements dealing respectively with Seabed Mining and Straddling and

Highly Migratory Fish Stocks.

Crimes at Sea, PIRACY AND SMUGGLING ON THE RISE

On the world’s oceans, piracy and armed robbery are on the rise. So is smuggling — especially of migrants

and drugs. Among the most widespread and serious at sea, these crimes are often masterminded by organized

criminals who take full advantage of weaknesses in law enforcement on the oceans. In some areas, they have

succeeded in undermining marine transport.

Maritime security and the safety of life at sea are also threatened by other criminal activities, such as terrorism, hijackings, the smuggling of arms and hazardous wastes, illegal fishing and dumping, the illegal discharge

of pollutants, and other violations of environmental laws.

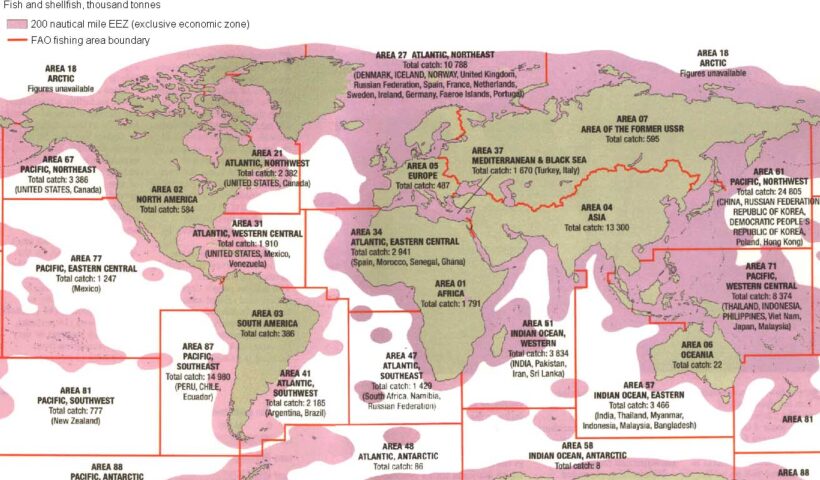

Marine Resources, AN OCEAN OF RICHES

Oceans are of enormous value to the world economy. They provide us with food, water, raw materials and

energy. The combined value of ocean resources and uses is estimated to be about $7 trillion per year. Fish and

minerals, including oil and gas, are among the most important marine resources, while the major uses of the

oceans include the recreation industry, transportation, communications and waste disposal.

The Marine Environment, ARE WE DESTROYING THE OCEANS?

The state of the world’s oceans continues to deteriorate. As new threats to the health and viability of the oceans

emerge, most of the problems identified decades ago have still not been solved and many have become worse,

according to a study carried out in 2001 by the United Nations Joint Group of Experts on the Scientific Aspects

of Marine Environmental Protection. At risk are the vast resources of the oceans and the many economic benefits that humanity derives from them, estimated to be about $7 trillion per year.

Coastal areas — the most productive marine environments — are the most affected. Currently more than

half of the world’s population lives within 100 kilometers of the coast, with two thirds of all cities with over

2.5 million inhabitants. By 2025, it is expected that 75 per cent of the world’s population will live in coastal

areas.

China geopolitical interests in eastern Asia and south china sea

The establishment of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) was proclaimed by Mao Zedong on October 1, 1949 at Tiananmen Square in Beijing. This followed two decades of almost constant turmoil that took the form of a prolonged civil war between the Nationalist Party, or Kuomintang (KMT), and the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) as well as the Japanese invasion of China, which resulted in the eight year Sino-Japanese War (1937–45). Following Chiang Kai-shek’s split with the CCP after his massacre of thousands of Communists in Shanghai in March 1927, the Nationalists were soon faced with a series of armed insurrections led by the Communists in cities such as Nanchang and Guangzhou. These uprisings ultimately proved unsuccessful. The Communists were driven into the countryside, where the Nationalists proceeded to wage a total of five campaigns of “extermination” between 1930 and 1934, aimed at achieving a comprehensive victory. The success of the fifth campaign in encircling and strangling the Communists led the latter to abandon their base in Jiangxi Province in October 1934 and stage the famous “Long March,” a 4,000-mile journey to establish a new base in Shaanxi in northwest China. China would soon be faced by the even greater threat of external invasion. The Japanese had established a presence in Manchuria by 1931. Growing domestic expansionist pressures led to an undeclared war with China following the “Marco Polo Bridge Incident” on July 7, 1937. Following the outbreak of hostilities, the Communists and Nationalists formed a “United Front” with the goal of defeating the Japanese, although the conflict between the CCP and the KMT was never resolved. Despite its initial success in taking many of the key coastal cities, including Shanghai, and eventually the Nationalist capital of Nanjing, the Japanese advance soon stalled. The Japanese army was never able to penetrate deep into the Chinese countryside. The Japanese surrender on August 14, 1945, following the dropping of atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, plunged China back into civil war. The Communists soon gained the upper hand, eventually driving the KMT out of China and into Taiwan, paving the way for the establishment of the People’s Republic of China.

View More China geopolitical interests in eastern Asia and south china seaRegime of the islands in law of the sea

Article 121 of the 1982 Convention deals with the regime of islands.

An island is a naturally formed area of land, surrounded by water, which is above water at high tide.

Except as provided for in paragraph 3, the territorial sea, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf of an island are determined in accordance with the provisions of this Convention applicable to other land territory.

Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.

difference between islands and rocks in law of the sea

The definition and treatment of islands in maritime boundary delimitation are complex and important. This is because the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which came into effect in 1994, provides that islands, along with mainland coasts, may generate a full suite of maritime zones – including a 200 nm exclusive economic zone (EEZ) and continental shelf claim as well as a 12 nm territorial sea. Thus, if no maritime neighbours were within 400 nm of the feature, an island has the potential to generate 125,664 sq. nm [431,014 km2] of territorial sea, EEZ and continental shelf rights. There is also the consideration that oceans remain an important source of living resources, with fisheries representing a major industry for many coastal states.

View More difference between islands and rocks in law of the seaThe Right to Seek Asylum in law of the sea

The 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, defines a refugee as a person who:“owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion, is outside the country of his [or her] nationality, and is unable to or, owing to such fear, is unwilling to avail himself [or herself ] of the protection of that country”. (Article 1A(2)) It further prohibits that refugees or asylum-seekers “… be expelled or returned in any way “to the frontiers of territories where his [or her] life or freedom would be threatened on account of his [or her] race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion.” (Article 33 (1)). The scope of the principle of non-refoulement has a larger scope in the field of Human Rights Law. Indeed, it protects every person and not only the refugees and asylum seeker and the scope of its protection is larger. Human Rights prohibits every expulsion or refoulement to a country where the person is at risk of suffering torture, inhuman or degrading treatment, sometimes the execution of the death penalty and sometimes a grave denial of justice.

View More The Right to Seek Asylum in law of the seaThe obligation to rescue people in distress at sea

Rescue of people in distress at sea, regardless of their nationality or status, is an unconditional obligation for all ships in vicinity and coastal state authorities. The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS Convention) provides that:

“ Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag, in so far as he can do so without serious danger to the ship, the crew or the passengers: (a) to render assistance to any person found at sea in danger of being lost; (b) to proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons in distress, if informed of their need of assistance, in so far as such action may reasonably be expected of him.” (Art. 98 (1))

Migrants’ rights at sea

The main rights and obligations concerning migrants attempting to cross the sea clandestinely are framed by the following legal norms: The right to leave any country, including his own and its limits

The 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides that:

“Everyone has the right to leave any country, including his own, and to return to his country” (Article 13. (2)). Article 5 of the 1965 International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination provides that state parties undertake to prohibit and to eliminate racial discrimination in all its forms and to guarantee the right of everyone, without distinction as to race, colour, or national or ethnic origin, to equality before the law, notably in the enjoyment of [c, ii)] the right to leave any country, including one’s own, and to return to one’s country.”

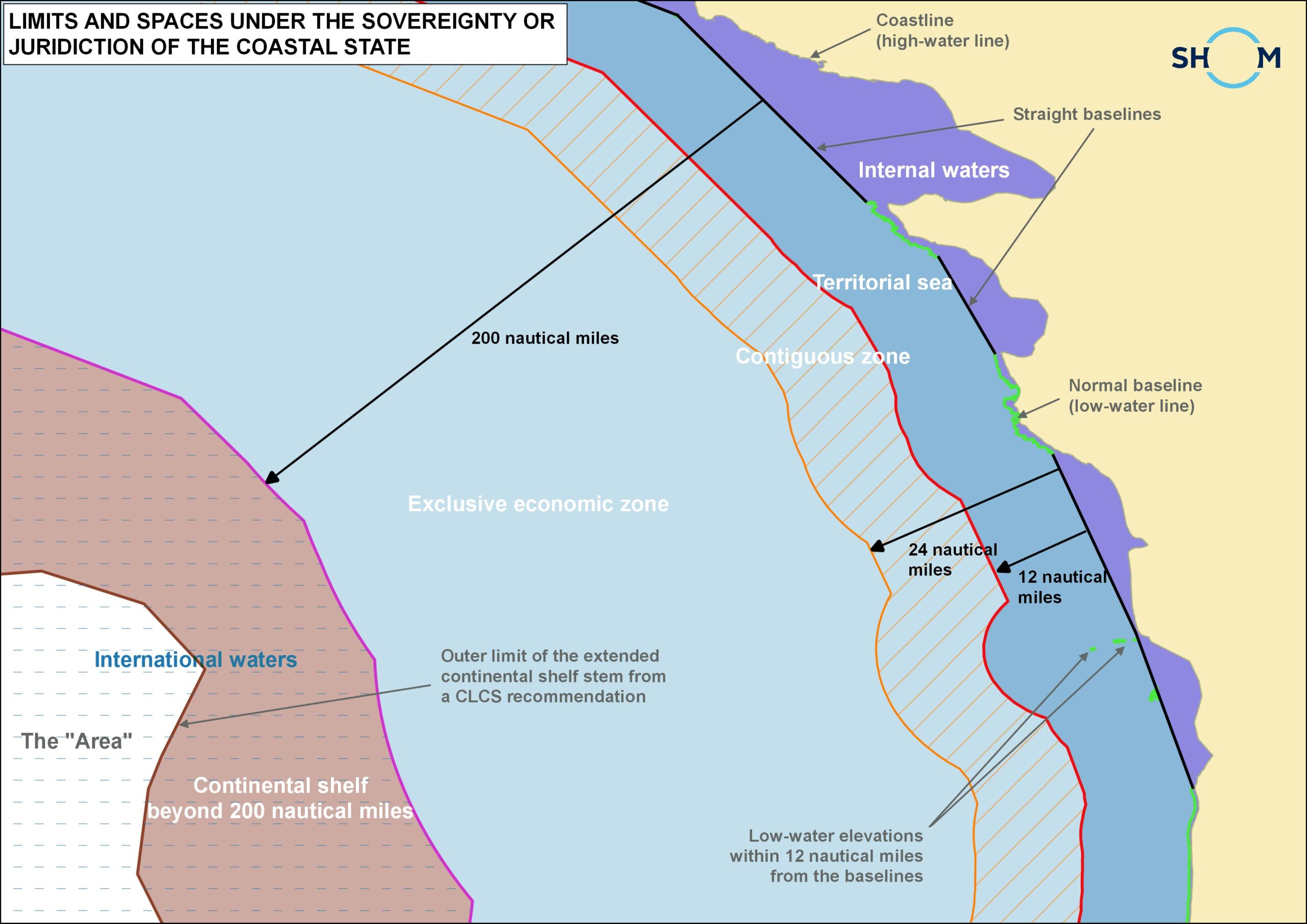

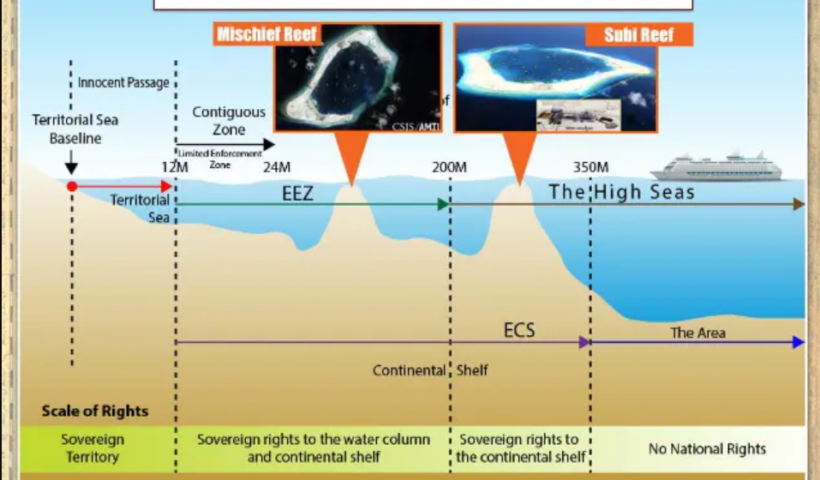

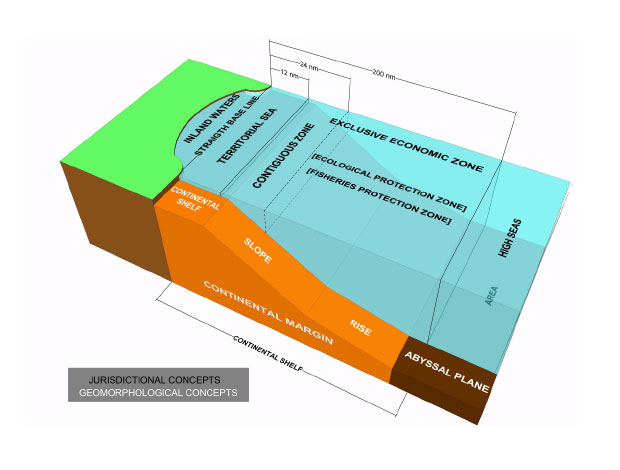

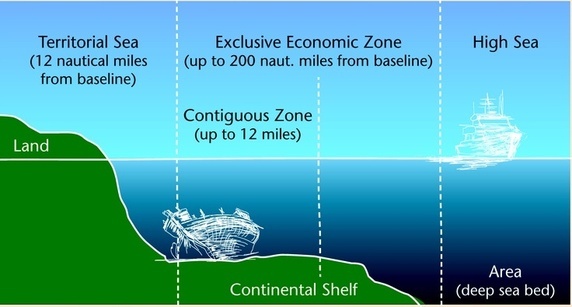

RIGHTS AND RESPONSIBILITIES IN MARITIME ZONES

Coastal states can claim five key maritime zones. Proceeding seawards from the coast they are internal waters, territorial seas, the contiguous zone, the exclusive economic zone (or, in some cases, an exclusive fishing zone) and the continental shelf. Archipelagic states may also claim archipelagic waters within their archipelagic baselines. Beyond these national zones of jurisdiction lie the international maritime zones of the high seas and the Area.

The rights of the coastal state and aliens vary in these maritime zones, and do so both spatially and functionally. Thus, the coastal state has more rights closer to shore, for example in internal waters and the territorial sea. Aliens retain considerable rights within a coastal state’s claimed maritime zones concerned with communication issues such as navigation, overflight and the laying of submarine cables and pipelines. The coastal state, in contrast, boasts significant resource related rights, particularly concerning fishing and mineral extraction from the seabed.

Exclusive Fishery Zones meaning and which countries have it?

where no EEZ claim has been made, several states instead claim an exclusive fishery zone. A significant proportion of these states border the Mediterranean Sea which has witnessed a dearth of EEZ claims.

The Mediterranean littoral states are not opposed to the EEZ concept in principle, but have been dissuaded from making EEZ claims because of ‘a twofold economico-geographic reason’. The geographical part of this reason relates to the fact that the physical dimensions of the Mediterranean preclude any coastal state from claiming an EEZ out to 200 nm from its baselines. The economic dimension refers to the the relatively unproductive nature of the Mediterranean from a fisheries perspective. Fishery zones have also been claimed by several states on behalf of their dependent territories.

what is the deference between national and international maritime zones?

The rights coastal states have in certain maritime zones, notably internal waters, the territorial sea and contiguous zone, affords them security in the face of threats such as smuggling, illegal immigration, other forms of cross-border crime and, ultimately, from the threat of terrorism and the use of military force. The national maritime zones outlined in the UN Convention also offer profound benefits to coastal states in respect of resources, both living resources such as fisheries and non-living resources such as oil and gas. Furthermore, the rights and responsibilities relating to national maritime zones as laid down in the 1982 Convention provide coastal states with opportunities and obligations in the sphere of ocean management. This includes, but is not limited to, navigation, fisheries protection, conservation of living resources, pollution control, search and rescue and marine scientific research.

View More what is the deference between national and international maritime zones?INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION FOR THE SAFETY OF LIFE AT SEA, 1974

The main objective of the SOLAS Convention is to specify minimum standards for the construction, equipment and operation of ships, compatible with their safety. Flag States are responsible for ensuring that ships under their flag comply with its requirements, and a number of certificates are prescribed in the Convention as proof that this has been done. Control provisions also allow Contracting Governments to inspect ships of other Contracting States if there are clear grounds for believing that the ship and its equipment do not substantially comply with the requirements of the Convention – this procedure is known as port State control. The current SOLAS Convention includes Articles setting out general obligations, amendment procedure and so on, followed by an Annex divided into 14 Chapters.

View More INTERNATIONAL CONVENTION FOR THE SAFETY OF LIFE AT SEA, 1974International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 relating thereto and by the Protocol of 1997 (MARPOL)

The International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL) is the main international convention covering prevention of pollution of the marine environment by…

View More International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships, 1973, as modified by the Protocol of 1978 relating thereto and by the Protocol of 1997 (MARPOL)Historical Development in legal issues on the Pollution from Ships

Ninety per cent of global trade is conducted by shipping, which is considered to be the most environmentally friendly form of transport, taking into account its productive value. Shipping contributes to a limited extent to marine pollution from human activities, in particular when compared to pollution from land-based sources (or even dumping). Protection of the environment was not the International Maritime Organization’s (hereinafter the IMO) original mandate. Its main interest was maritime safety. However, in 1954 the IMO became the depository of the first 1954 Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Oil (hereinafter the OILPOL, see further below). Since then the protection of the marine environment has become one of the most important activities of the IMO. Among fifty-one treaty instruments the IMO has adopted so far, twenty-one are directly environment-related (twenty-three if we include the Salvage and Wreck Removal Conventions). The Marine Environment Protection Committee is the IMO’s technical body in charge of marine pollution related matters (it is aided in its work by a number of Sub-Committees).

View More Historical Development in legal issues on the Pollution from Ships