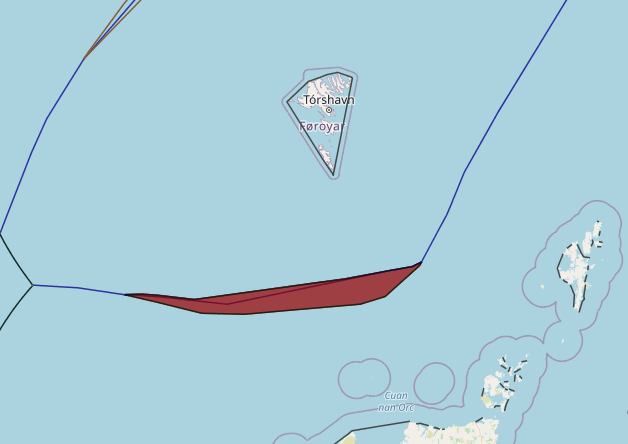

Navigational regimes are crucial for ensuring the safe and efficient movement of vessels through international waterways. These regimes consist of a set of rules and regulations that govern navigation, safety, and access to specific areas. The Bosporus and Dardanelles Straits, located in Turkey, are two prominent examples of navigational regimes that have significant geopolitical and economic implications. This article will analyze the navigational regimes of the Bosporus and Dardanelles, exploring their historical background, the role of international maritime law, environmental concerns, impact on trade and global economy, security challenges, technological advancements, collaborative efforts, and a case study of successful implementation.

View More Analyzing Navigational Regimes: Bosporus and DardanellesAnalyzing Navigational Regimes: Bosporus and Dardanelles

IILSS 27th September 2023

Analyzing Navigational Regimes: Bosporus and DardanellesBosporusBosporus and DardanellesDardanellesHow deep is the Bosporus Dardanelles channel?How deep is the Dardanelles Strait?How wide is Bosporus and Dardanelles?Technological Advances in Navigating the StraitsThe Dardanelles and Bosporus PassagesThe Significance of the Bosporus and Dardanelles StraitsWhat are the Dardanelles and the Bosporus?What do Dardanelles connect?Where is Bosporus and Dardanelles?Who were the British fighting against in the Dardanelles?Why are the Bosporus and Dardanelles important?Why are the Bosporus and Dardanelles straits significantWhy is the Bosporus and Dardanelles important?Why was the Dardanelles so important?