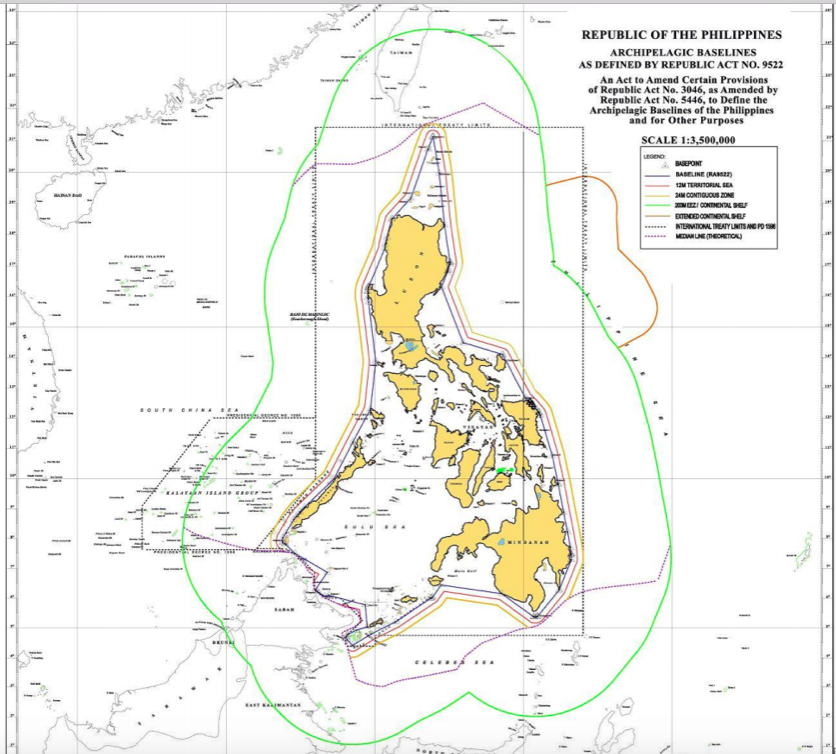

the list of geographical coordinates of points as contained in Republic Act No. 9522: An Act to Amend Certain Provisions of Republic Act No. 3046, as Amended by Republic Act No. 5446, to Define the Archipelagic Baselines of the Philippines, and for Other Purposes

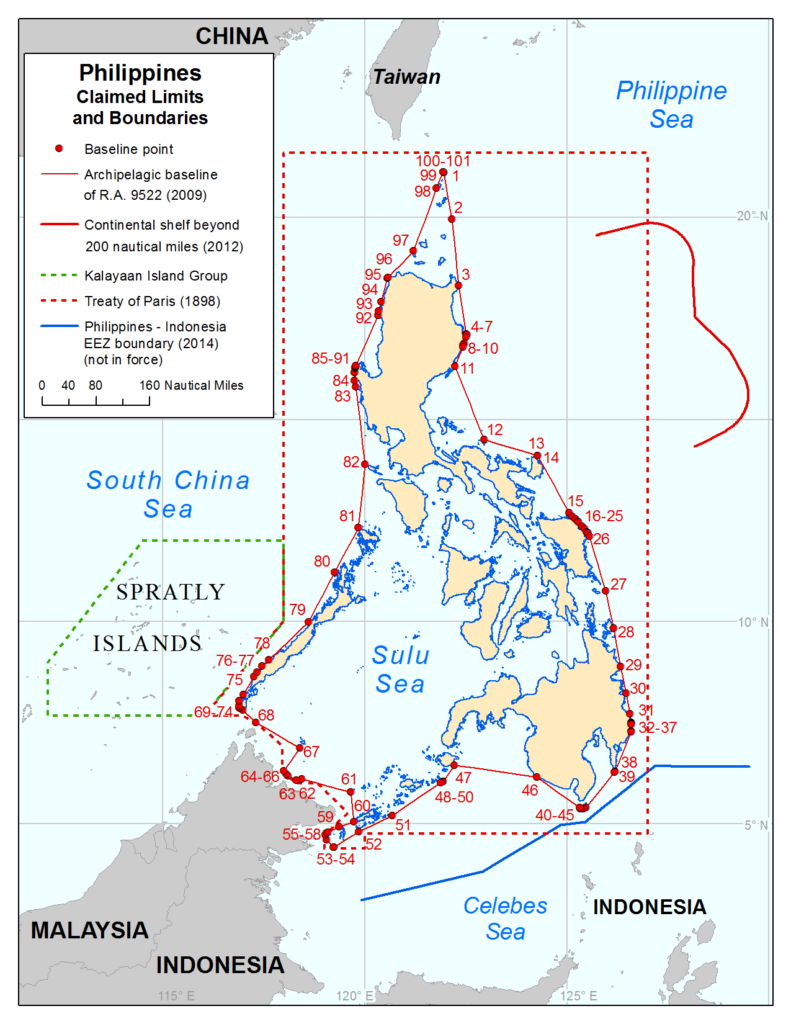

The archipelagic baseline system of the Philippines is composed of 101 line segments, ranging in length from 0.08 nm (segment 99-100) to 122.88 nm (segment 46-47), with a total length of 2,808 nm. The archipelagic baseline system includes all of the Philippines’ main islands and does not include Scarborough Reef or the Kalayaan Island Group.

The archipelagic baseline system of the Philippines meets the water-to-land-area ratio set forth in Article 47.1:

Total Area = 887,909 square kilometers

Water Area = 589,739 square kilometers

Land Area = 298,170 square kilometers

Water-to-land area ratio = 1.98 to 1

Consistent with Article 47.2 of the LOS Convention, three baseline segments (11-12, 46-47, and 82-83), which comprise 2.97 percent of the total number of segments, exceed 100 nm in length; none of the segments exceed 125 nm. Annex 2 to this study (R.A. 9522) lists the lengths of each segment. Our separate analysis of the baseline segments and the results confirm what is listed in R.A. 9522.

The configuration of the baselines does not appear to depart to any appreciable extent from the general configuration of the archipelago (Article 47.3). None of the baselines appear to be drawn using low-tide elevations (Article 47.4). The baselines are not drawn in a way that would cut off from the high seas or EEZ the territorial sea of another State (Article 47.5).

Therefore, the Philippines’ archipelagic baseline system set forth in R.A. 9522 appears to be consistent with Article 47 of the LOS Convention.

Internal Waters and Archipelagic Waters

Article 1 of the Philippine Constitution provides that “[t]he waters around, between, and connecting the islands of the archipelago, regardless of their breadth and dimensions, form part of the internal waters of the Philippines.” Upon signing the LOS Convention in 1982 and again in ratifying the Convention in 1984, the Philippines stated: “The concept of archipelagic waters [under the LOS Convention] is similar to the concept of internal waters under the Constitution of the Philippines.” The United States and other countries have protested this understanding. In response, the Philippines stated in 1988 that it “intends to harmonize its domestic legislation with the provisions of the Convention” and that it “will abide by the provisions of the said Convention.”

In 2009, through its R.A. 9522, the Philippines established new archipelagic baselines; however, this legislation did not clarify whether the waters within the baselines are archipelagic waters (rather than internal waters), as provided for in the LOS Convention. In July 2011, the Philippine Supreme Court considered the question of whether R.A. 9522 “unconstitutionally ‘converts’ internal waters into archipelagic waters, hence subjecting these waters to the right of innocent and sea lanes passage under [the LOS Convention].” In unanimously upholding the constitutionality of R.A. 9522, the Philippine Supreme Court stated that “[w]hether referred to as Philippine ‘internal waters’ under Article I of the Constitution or as ‘archipelagic waters’ under [Article 49 of the LOS Convention], the Philippines exercises sovereignty over the body of water lying landward of the baselines.” The court recognized that Philippine sovereignty over the waters within the baselines is subject to the rights of innocent passage and archipelagic sea lanes passage, as provided for under international law.

In 2011, the “Philippine Maritime Zones Act” was introduced in the Philippine Congress, Section 4 of which would clarify, consistent with the LOS Convention, that “[t]he Archipelagic Waters of the Philippines refer to the waters on the landward side of the archipelagic baselines …” and that “[w]ithin the archipelagic waters, closing lines for the delimitation of internal water shall be drawn pursuant to Article 50 of [the LOS Convention]….”16 This legislation, whichwould confirm that the Philippines is treating these waters in a manner consistent with the LOS Convention, has not yet been enacted into law.

Territorial Sea, Exclusive Economic Zone, and Continental Shelf

R.A. 3046 of June 17, 1961 defined the territorial sea of the Philippines as follows: “all the waters within the limits set forth in the [Treaty of Paris between the United States and Spain of 1898, the treaty between the United States and Spain of November 7, 1900, and the treaty between the United States and Great Britain of January 2, 1930] have always been regarded as part of the territory of the Philippine Islands.”

R.A. 9522 of 2009, which modified R.A. 3046, provides that the territorial sea of the Philippines is to be measured from the baselines established in that Act. Likewise, in its decision of July 2011, the Philippine Supreme Court referred to the applicability of Article 48 of the LOS Convention to the maritime zones of the Philippines as follows: “The breadth of the territorial sea [and other maritime zones] shall be measured from archipelagic baselines drawn in accordance with article 47 [of the LOS Convention].” (Emphasis supplied by the court.) R.A.9522, however, did not specify the breadth of the territorial sea of the Philippines.

Presidential Decree No. 1599 of June 11, 1978, established a 200-nm EEZ measured from the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea is measured.

Presidential Proclamation No. 370 of March 20, 1968, claimed jurisdiction and control over the mineral and other natural resources of the continental shelf adjacent to the Philippines “to where the depth of the superjacent waters admits of the exploitation of such resources.” On April 8,2009, the Philippines made a submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS) concerning the continental shelf beyond 200 nm in the Benham Rise (Benham Plateau) region, east of the Philippines in the Philippine Sea. On April 12, 2012, the CLCSgave supportive recommendations concerning this submission, and on July 2, 2012, the Philippines delineated the outer limits of its continental shelf in the Benham Rise region on the basis of those recommendations.

For Scarborough Reef and the Kalayaan Island Group, Section 2 of R.A. 9522 refers to the applicability of the “Regime of Islands” under Article 121 of the LOS Convention. In the context of an arbitration case brought against China under Annex VII of the LOS Convention, the Philippines has taken the view that Scarborough Reef and at least some of the islands within the Kalayaan Island Group fall under paragraph 3 of Article 121 as “[r]ocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own” and therefore “have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.” In response to R.A. 9522, China protested the Philippines’sovereignty claims to these features and reiterated its own claims.

Navigation

Upon signing and ratifying the LOS Convention, the Philippines stated that “[t]he concept of archipelagic waters is similar to the concept of internal waters under the Constitution of the Philippines.” In its 1986 protest of this characterization, the United States stated the following:

…as generally understood in international law, including that reflected in the 1982 Law of the Sea Convention, the concept of internal waters differs significantly from the concept of archipelagic waters. Archipelagic waters are only those enclosed by properly drawn archipelagic baselines and are subject to the regimes of innocent passage and archipelagic sea lanes passage.

Articles 52 and 53 of the LOS Convention describe the rights of innocent passage and archipelagic sea lanes passage, respectively. In upholding the constitutionality of R.A. 9522, the Supreme Court of the Philippines stated that the right of innocent passage is a matter of customary international law and thus part of Philippine law and applies both in the archipelagic waters and territorial sea of the Philippines. The Court also recognized that the right of archipelagic sea lanes passage applies in those waters, and that “the Philippine government . . . may pass legislation designating routes within the archipelagic waters to regulate . . . sea lanes passage.

An archipelagic State may designate such sea lanes, and also traffic separation schemes, provided that “an archipelagic State shall refer [such] proposals to the competent international organization with a view to their adoption” (LOS Convention, Article 53, paragraphs 1 and 9). As the competent international organization, the International Maritime Organization (IMO) may “adopt only such sea lanes and traffic separation schemes as may be agreed with the archipelagic State, after which the archipelagic State may designate, prescribe, or substitute them” (Article 53.9). As of August 2014, the Philippine government had not formally designated any archipelagic sea lanes, nor had it presented proposals to this effect to the IMO. Since no archipelagic sea lanes have beendesignated in accordance with the LOS Convention, the “right of archipelagic sea lane passage may be exercised through the routes normally used for international navigation” (Article 53.12).

Exclusive Economic Zone Jurisdiction

Section 4 of Presidential Decree No. 1599 of June 11, 1978 recognized that “[o]ther States shall enjoy in the exclusive economic zone freedoms with respect to navigation and overflight, the laying of submarine cables and pipelines, and other internationally lawful uses of the sea relating to navigation and communications.” The provisions of international law to which the Proclamation refers are reflected in the LOS Convention, Parts V (pertaining to the EEZ); VI (pertaining to the continental shelf, including Article 79 pertaining to submarine cables and pipelines); and VII (pertaining to the high seas).

Maritime Boundaries

The Philippines has established a maritime boundary with Indonesia. The Philippines and Indonesia concluded a maritime boundary agreement in May 2014 (not yet in force) that establishes an EEZ boundary and is without prejudice to the delimitation of the continental shelf boundary between the two countries. The EEZ boundary provided for in the agreement is 627nm in length and composed of geodesic lines connecting eight points.

As of August 2014, the Philippines had not yet established maritime boundaries with Japan, China, Malaysia, Palau, and Taiwan. Malaysia may consider that it has already established amaritime boundary with the Philippines.

With respect to the EEZ, Section 1 of Decree No. 1599 provides “where the outer limits of the zone as thus determined overlap the exclusive economic zone of an adjacent or neighbouring State, the common boundaries shall be determined by agreement with the State concerned or in accordance with pertinent generally recognized principles of international law on delimitation.”