The right of innocent passage through the territorial sea is based on the freedom of navigation as an essential means to accomplish freedom of trade. In his book published in 1758, Emer de Vattel had already accepted the existence of such a right. Subsequently, in the Twee Gebroeders case of 1801, Lord Stowell ruled that: ‘[T]he act of inoffensively passing over such portions of water, without any violence committed there, is not considered as any violation of territory belonging to a neutral state – permission is not usually required.’ It may be considered that the right of innocent passage became established in the middle of the nineteenth century. In this regard, the Report Adopted by the Committee on 10 April 1930 at the Hague Conference for the Codification of International Law clearly stated:

This sovereignty [over the territorial sea] is, however, limited by conditions established by international law; indeed, it is precisely because the freedom of navigation is of such great importance to all States that the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea has been generally recognised.

At the treaty level, the right of innocent passage was, for the first time, codified in Article 14(1) of the TSC. This provision was followed by Article 17 of the LOSC, which provides:

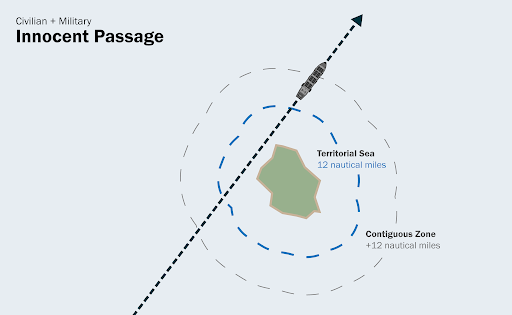

Subject to this Convention, ships of all States, whether coastal or land-locked, enjoy the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea.

It is important to note that the right of innocent passage does not comprise the freedom of overflight.

Under Article 18(1) of the LOSC, innocent passage comprises lateral passage and inward/outward-bound passage. Lateral passage is the passage traversing the territorial sea without entering internal waters or calling at a roadstead or port facility outside internal waters. Inward/outward-bound passage concerns the passage proceeding to or from internal waters or a call at such roadstead or port facility. As will be seen, the direction of the passage is at issue in relation to the criminal jurisdiction of coastal States over vessels of foreign States in the territorial sea. The LOSC contains several rules concerning the manner of innocent passage through the territorial sea.

First, passage shall be continuous and expeditious. This means that ships are required to proceed with due speed, having regard to safety and other relevant factors. Under Article 18(2), passage includes stopping and anchoring only in so far as the same are incidental to ordinary navigation or are rendered necessary by force majeure or distress or for the purpose of providing assistance to persons, ships or aircraft in danger or distress.

Accordingly, the act of hovering by a foreign vessel is not normally considered innocent passage.

Second, in the territorial sea, submarines and other underwater vehicles are required to navigate on the surface and to show their flag pursuant to Article 20. This provision follows essentially from Article 14(6) of the TSC. In this respect, the question arises as to whether a breach of the requirement to navigate on the surface can be the negation of the right of innocent passage. While it seems that a submerged submarine in the territorial sea is not considered as innocent passage, submergence in the territorial sea will not instantly justify the use of force against the submarine. Above all, every measure should be taken short of armed force to require the submarine to leave.

Third, foreign ships exercising the right of innocent passage through the territorial sea shall comply with all such laws and regulations and all generally accepted international regulations relating to the prevention of collisions at sea in accordance with Article 21(4). The most important regulations are probably those in the 1972 Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea. Concerning innocent passage, the question arises as to when passage becomes prejudicial and hence non-innocent. In this respect, Article 19(1) of the LOSC, which is a replica of

Article 14(4) of the TSC, provides:

Passage is innocent so long as it is not prejudicial to the peace, good order or security of the coastal State. Such passage shall take place in conformity with this Convention and with other rules of international law. More specifically, Article 19(2) contains a catalogue of prejudicial activities: (a) any threat or use of force, (b) any exercise with weapons of any kind, (c) spying, (d) any act of propaganda, (e) the launching, landing or taking on board of any aircraft, (f ) the launching, landing or taking on board of any military device, (g) the loading or unloading of any commodity, currency or person contrary to the customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws of the coastal State, (h) any act of wilful and serious pollution, (i) fishing activities, (j) research or survey activities, (k) interference with coastal communications or any other facilities, and (l) any other activity not having a direct bearing on passage. The last item in the list, (l), seems to imply that the above list is non-exhaustive. Article 19 calls for four comments.

First, the term ‘activities’ under Article 19(2) seems to suggest that the prejudicial nature of innocent passage is judged on the basis of the manner in which the passage is carried out, not the type of ship. This approach seemed to be echoed by the ICJ in the 1949 Corfu Channel case. In that case, the Court relied essentially on the criterion of ‘whether the manner in which the passage was carried out was consistent with the principle of innocent passage’.

Second, some clauses of Article 19(2) are so widely drafted that disputes may arise with respect to their interpretation. For instance, Article 19(2)(a) refers to ‘or in any other manner in violation of the principles of international law embodied in the Charter of the United Nations’. Arguably, this reference may provide wide discretion to the coastal State. Similarly,

the coastal State may have wide discretion in the interpretation of Article 19(2)(c), ‘any act aimed at collecting information to the prejudice of the defence or security of the coastal State’ and (j), ‘the carrying out of research or survey activities’. In response to possible disagreements concerning the interpretation of Article 19(2), for instance, paragraph 4 of the 1989 Uniform Interpretation between the United States and the USSR stated:

A coastal State which questions whether the particular passage of a ship through its territorial sea is innocent shall inform the ship of the reason why it questions the innocent passage, and provide the ship an opportunity to clarify its intentions or correct its conduct in a reasonably short period of time.

Third, a question arises of whether paragraph 2 of Article 19 is meant to be an illustrative list of paragraph 1 of the same provision, or whether the coastal State may evaluate innocence solely on the basis of paragraph 1, independent from paragraph 2. If paragraph 2 is an illustrative list of paragraph 1, paragraph 1 would seem to be superfluous. Unlike the second paragraph, the first paragraph makes no explicit reference to ‘activities’. Hence there appears to be scope to argue that the criterion for judging innocence under Article 19(1) is not limited to the manner of the passage of ships. At least, there is no clear evidence that the criteria for evaluating innocence of the passage of foreign warships in paragraphs 1 and 2 of Article 19 must be the same. If this is the case, it seems that the coastal State can regard the particular passage of a ship as non-innocent on the basis of Article 19(1), even if the passage concerned does not directly fall within the list of Article 19(2). Following this interpretation, for instance, the Japanese government takes the view that the passage of foreign warships carrying nuclear weapons through its territorial sea is not innocent, while Japan generally admits the right of innocent passage of foreign warships.

Fourth, a question that may arise is whether a violation of a coastal State’s law would ipso facto deprive a passage of its innocent character. While the opinion of the members of the ILC was divided on this particular issue, the literal interpretation of Article 14(4) of the TSC appears to suggest that the violation of the coastal State’s law does not ipso

facto deprive a passage of its innocent character, unless such violation is prejudicial to the coastal State’s interests. The only exception involves Article 14(5), which provides:

Passage of foreign fishing vessels shall not be considered innocent if they do not observe such laws and regulations as the coastal State may make and publish in order to prevent these vessels from fishing in the territorial sea.

This provision was inserted in order to introduce an additional criterion of innocence. It seems to imply that apart from the violation of fishing law, the breach of the law of the State does not ipso facto deprive a passage of its innocence. Likewise, there appears to be scope to argue that, under the LOSC, the violation of the law of the coastal State does not ipso facto deprive a passage of its innocent character, unless such violation falls within the scope of Article 19.