The Concept of the Contiguous Zone

The contiguous zone is a marine space contiguous to the territorial sea, in which the coastal State may exercise the control necessary to prevent and punish infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations within its territory or territorial sea.

The development of the contiguous zone was a complicated process of concurrence of different claims by coastal States. While the origin of the concept of the contiguous zone dates back to the Hovering Acts enacted by Great Britain in the eighteenth century, it was not until 1958 that rules governing the contiguous zone were eventually agreed, enshrined in Article 24 of the TSC. Later, this provision was, with some modifications, reproduced in Article 33 of the LOSC.

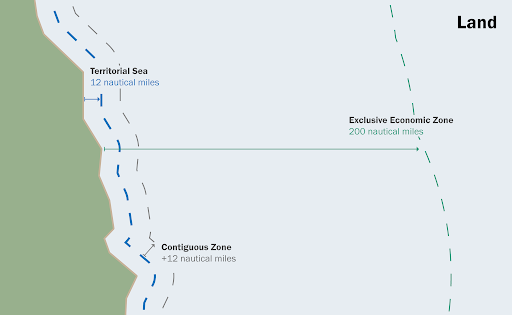

The landward limit of the contiguous zone is the seaward limit of the territorial sea. Under Article 33(2) of the LOSC, the maximum breadth of the contiguous zone is 24 nautical miles. Article 33 of the LOSC contains no duty corresponding to Article 16, which obliges the coastal State to give due publicity to charts. It would seem to follow that there is no specific requirement concerning notice in the establishment of the contiguous zone. The contiguous zone is an area contiguous to the high seas under Article 24(1) of the TSC. Under the LOSC, the contiguous zone is part of the EEZ where the coastal State claims the zone. Where the coastal State does not claim its EEZ, the contiguous zone is part of the high seas. At present, some ninety States claim a contiguous zone.

Coastal State Jurisdiction Over the Contiguous Zone

Article 33(1), which follows Article 24(1) of the TSC, provides:

In a zone contiguous to its territorial sea, described as the contiguous zone, the coastal State may exercise the control necessary to:

(a) prevent infringement of its customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations within its territory or territorial sea;

(b) punish infringement of the above laws and regulations committed within its territory or territorial sea.

This provision requires three brief comments.

First, Article 33(1) contains no reference to internal waters. However, it would be inconceivable that the drafters of this provision intended to exclude the internal waters from the scope of this provision since these waters are under the territorial sovereignty of the coastal State. Thus it appears to be reasonable to consider that internal waters are also

included in the scope of ‘its territory or territorial sea’.

Second, Article 33(1) literally means that the coastal State may exercise only enforcement, not legislative, jurisdiction within its contiguous zone. It would follow that relevant laws and regulations of the coastal State are not extended to its contiguous zone; and that infringement of municipal laws of the coastal State within the zone is outside the scope of this provision. Considering that an incoming vessel cannot commit an offence until it crosses the limit of the territorial sea, it would appear that head (b) of Article 33(1) can apply only to an outgoing ship. By contrast, head (a) can apply only to incoming ships because prevention cannot arise with regard to an outgoing ship in the contiguous zone.

Third, Article 33(1) does not make the further specification with regard to ‘control necessary to punish infringement’ of municipal law of the coastal State in its contiguous zone. In this regard, Article 111(1) makes clear that the coastal State may undertake the hot pursuit of foreign ships within the contiguous zone. Article 111(6), (7) and (8) further provide the coastal State’s right to stop a ship, the right to arrest the ship, and the right to escort the ship to a port. One can say, therefore, that the coastal State jurisdiction to punish the infringement of its municipal laws in the contiguous zone includes these rights. Article 111(1) does not specify the place where the infringement of laws and regulations of the coastal State must have occurred. In view of maintaining consistency with Article 33(1), it appears reasonable to consider that the coastal State may commence the hot pursuit of a ship only where that ship has already breached the laws and regulation of that State within its territory or territorial sea. On the other hand, literally taken, the incoming ships cannot have committed a breach of municipal law of the coastal State before they cross the boundary of the territorial sea. In this case, therefore, there may be room for the view that ‘control’ does not include arrest or forcible taking into port. The legal nature of the coastal State jurisdiction over the contiguous zone is not free from controversy. According to a literal or restrictive view, the coastal State has only enforcement jurisdiction in its contiguous zone and, consequently, action of the coastal State may only be taken concerning offences committed within the territory or territorial sea of the coastal State, not in respect of anything done within the contiguous zone itself. Sir Gerald Fitzmaurice is a leading writer supporting this view. According to Fitzmaurice, the power over the contiguous zone is ‘essentially supervisory and preventative’.

According to a liberal view, the coastal State may regulate the violation of its municipal law within the contiguous zone for some limited purposes. For instance, Oda argued that in the contiguous zone, the coastal State should be entitled to exercise its authority as exercisable in the territorial sea only for some limited purposes of customs or sanitary control. O’Connell echoed this view.

There appears to be little doubt that a strict reading of Article 33(1) does not allow coastal States to extend legislative jurisdiction to its contiguous zone. There is an exception, however. Concerning the protection of objects of an archaeological and historical nature found at sea, Article 303(2) of the LOSC provides:In order to control traffic in such objects, the coastal State may, in applying Article 33, presume that their removal from the seabed in the zone referred to in that article without its approval would result in an infringement within its territory or territorial sea of the laws and

regulations referred to in that article.

This provision relies on a dual legal fiction. First, the removal of archaeological and historical objects is to be regarded as infringement of customs, fiscal, immigration or sanitary laws and regulations of the coastal State. Second, the removal of archaeological and historical objects within the contiguous zone is to be considered as an act within the territory or the territorial sea. By using the dual fiction, the removal of archaeological and historical objects within the contiguous zone is subject to the control of the coastal State, including hot pursuit. Thus, as far as the prevention of the removal of archaeological and historical objects is concerned, the coastal State may exercise legislative and enforcement jurisdiction within its contiguous zone by virtue of Article 303(2).

Currently the contiguous zone is part of the EEZ when the coastal State claimed the zone. As will be seen, in the EEZ the coastal State may exercise both legislative and enforcement jurisdiction for limited matters provided by the law of the sea. Considering that the contiguous zone is becoming important for the purpose of regulation of illegal traffic in drugs, claims to legislative jurisdiction in the zone will not cause a serious problem in reality. If this is the case, as a matter of practice, it may not be unreasonable to extend the legislative jurisdiction of the coastal State over the contiguous zone for the limited purposes provided in Article 33 of the LOSC. In any case, it must be remembered that disputes with regard to the exercise by a coastal State of its jurisdiction over the contiguous zone fall within the scope of the compulsory settlement procedure in Part XV of the LOSC.