In parallel with the codification process in the 1958 Geneva Conventions and the 1982 UNCLOS, the law of maritime delimitation was subject to a progressive development through litigation and arbitration. Both processes were at the same time independent and interrelated. The scope of this part is to provide a broad historical background of the evolution of the case law of maritime delimitation in order to better analyze in the following section the conditions, under which the Equidistance/Relevant Circumstances principle had emerged and developed.

Development of the Equitable Principles

The wide spectrum of case law on maritime delimitation ranges broadly speaking from equity to normativity. The notion of equity is a “constitutional principle” of the law of maritime delimitation developed in the early cases of disputes on overlapping titles. At this point, it is important to know what the definition and the methodology of the legal concept of equity are.

The legal concept of equity in the law of maritime delimitation did not originated from any conventional law before the adoption of the 1982 UNCLOS. It was recognized for the first time as international customary rule in matters of continental shelf delimitation by the ICJ in the North Sea Continental Shelf case in respect of the Truman Proclamation (1945), which read as follows:

The United States regards the natural resources of the subsoil and seabed of the continental shelf beneath the high seas but contiguous to the coasts of the United States, subject to its jurisdiction and control. In cases where the continental shelf extends to the shores of another States, or is shared with an adjacent State, the boundary shall be determined by the United States and the State concerned in accordance with equitable principles.

On the basis of the Truman proclamation considered in that way as customary rule, the Court set out the legal framework on which a delimitation process ought to be carried out. The first principle is “agreement” and the second is “equitable principles” as expressed in the decision of the ICJ:

Those principles being that delimitation must be the object of agreement between the States concerned, and that such agreement must be arrived at in accordance with equitable principles.

More explicitly, “equitable principles” contains the idea of equity. The emphasis here is not the method of delimitation but the goal to secure justice in any delimitation process. In so doing, specific factors peculiar to circumstances of the case, otherwise called “equitable principles”, must be taken into account in the process of delimitation, specifically the principle of natural prolongation of the land territory (soil and subsoil), the principle of non encroachment of the territory of another State (soil, subsoil and coastal geography) and the principle of proportionality. In other words, equity bases any delimitation on the specific circumstances of the case. It is a case-by-case solution. The principle of equity had been confirmed in subsequent cases, for instance the Continental Shelf case between Tunisia and Libya, where the ICJ reaffirmed equity as a general principle of international law grafted onto customary law and not assimilable to a decision ex aequo et bono:

Equity as a legal concept is a direct emanation of the idea of justice. […] the legal concept of equity is a general principle directly applicable as law. Moreover, when applying positive international law, a court may choose among several possible interpretations of the law the one which appears, in the light of the circumstances of the case, to be closest to the requirement of justice. Application of equitable principles is to be distinguished from a decision ex aequo et bono. The equitable approach of delimitation was subject to further development in the subsequent case law of maritime delimitation, specifically in the Tunisia/Libya case (1982), the Gulf of Maine case (1984), the Libya/Malta case (1985), the Guinea/Guinea Bissau case (1985) and St Pierre and Miquelon case (1992). This concept, which declined in the beginning of the 1990’s, is not exempt from criticism as will be seen later.

Decline of Equitable Principles and Rise of Normativity

An analysis of the historical background of the development of the case law of maritime delimitation shows a progressive shift from equity to normativity in the subsequent cases adjudicated in the beginning of the 1990’s. However, in reality, the milestone of the normativity principle in the case law of maritime delimitation had been set out from the Anglo-French Continental shelf case (1977) between France and United Kingdom, where the Court of Arbitration held that The role of the ‘special circumstances’ condition in Article 6 is to ensure an equitable delimitation; and the combined ‘equidistance-special circumstances rule’, in effect, gives particular expression to a general norm that, failing agreement, the boundary between States abutting on the same continental shelf is to be determined on equitable principles.

In this particular case, the Court of Arbitration applied to some areas to be delimited Article 6 of the 1958 Convention on the Continental Shelf case on the basis that this Convention grafted onto treaty law serves the purpose of equitable principles founded in customary law. Consequently, as stated by Tanaka, “The assimilation of Article 6 to customary law leads to an important consequence: the incorporation of the equidistance method into customary law”.

More explicitly, the normative approach founded the law applicable to maritime delimitation on a set of codified rules contained either into the 1958 Geneva Conventions, into the 1982 UNCLOS or into precedent jurisdictional decisions. Normativity advocates equity of the rule and not equity of the particular case as for equitable principles. Consequently, as recognized by Tanaka, the normativization process of maritime delimitation is mainly based on incorporation of a specific method of delimitation into customary law. This method as consolidated under treaty law is the equidistance principle, which has the advantage of certainty and predictability and can, therefore, be used to correct the inequity of the particular case.

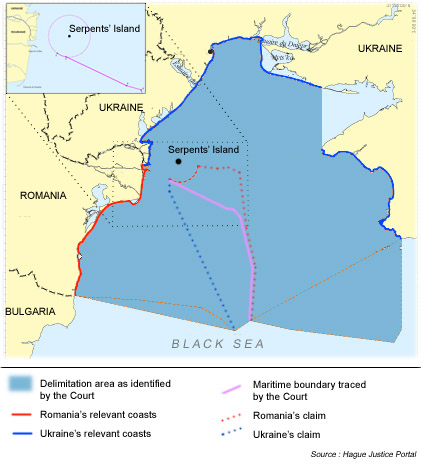

Hence, the rise of normativity in the development of the case law of maritime delimitation has led to the drawing up of a specific principle of delimitation, recognized as the Equidistance/Relevant Circumstances. This approach has been reflected in the decisions of relevant cases, such as Greenland/Jan Mayen (1993), Eritrea/Yemen (1999), Qatar/Bahrain (2001), Cameroon/Nigeria (2002), Barbados/Trinidad and Tobago (2006), Guyana/Suriname (2007) and Romania/Ukraine (2009).

What characterizes specifically the concept of Equidistance/Relevant Circumstances? How had it emerged and been developing in the law of maritime delimitation?