In theory, the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone could follow a different line than the continental shelf. For practical reasons, however, states seem to have wanted to have their maritime zones delimited by a single maritime boundary for all purposes. The reason for this lies first of all in the shared overlap of natural resources between the two zones.

Both zones give rights to living and non-living natural resources in the seabed and its subsoil, but with the limitation that the rights of continental shelf are limited to certain ‘sedentary species’ such as coral, oysters, sponges and possibly lobsters and crabs. Therefore, as held in the Libya/Malta case, whereas ‘there can be a continental shelf where there is no exclusive economic zone, there cannot be an exclusive economic zone without a corresponding continental shelf.’ Thus, having the same boundary delimiting the seabed and subsoil and the water column above seems practical in terms of exploiting the area in a proper way and maintaining effective coastal management. Having clear and manageable maritime zones can also be said to be conflict-preventive. On the other hand, this desire for a single maritime boundary for all purposes gave rise to a serious dilemma in the delimitation of these zones. As the relevant circumstances to be taken into account may differ for the seabed and for the superjacent water column, the boundary of the continental shelf and the EEZ may differ.

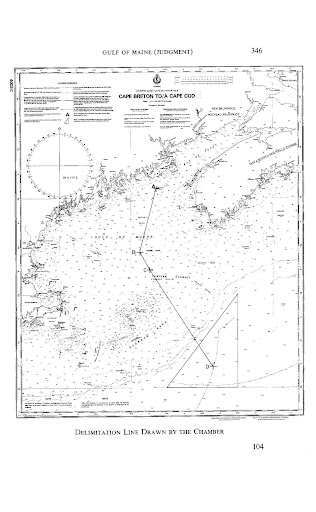

The 1984 Gulf of Maine case between Canada and the United States was the first to involve a single maritime boundary adjudicated by an international dispute settlement body. Both Canada and the United States had ratified the Convention on the Continental Shelf. At the same time they had asked the Court to draw up a single maritime boundary applicable to both the fishery zone and the continental zone. The Court held that the Convention on the Continental Shelf ‘cannot have such mandatory force between States which are Parties to the Convention, as regards a maritime boundary concerning a much wider subject-matter than the continental shelf alone’. By this the Court considered the Convention on the Continental Shelf as not regulating the matter when the issue at hand involves delimiting more than just the continental shelf. As there was no treaty law regulating a single maritime boundary at the time of the Gulf of Maine case, the Court had to rely on customary law. In this respect it referred to a ‘fundamental norm’ applicable to every maritime delimitation between states. The Court was now faced with the dilemma indicated above – how to treat the possibility that a criterion suitable for one maritime zone differs from one appropriate to that of another. To steer clear of this problem, the Court established a ‘neutral criterion’:

In reality, a delimitation by a single line, such as that which has to be carried out in the present case, i.e., a delimitation which has to apply at one and the same time to the continental shelf and to the superjacent water column can be carried out only by the application of a criterion, or combination of criteria, which does not give preferential treatment to one of these two objects to the detriment of the other, and at the same time is such as to be equally suitable to the division of either of them. In that regard, moreover, it can be foreseen that with the gradual adoption by the majority of maritime states of an exclusive economic zone and, consequently, an increasingly general demand for single delimitation, so as to avoid as far as possible the disadvantages inherent in a plurality of separate delimitations, preference will henceforth inevitably be given to criteria that, because of their more neutral character, are best suited for use in a multi-purpose delimitation.’

As a consequence, geological and geomorphological circumstances relevant for the delimitation of the continental shelf were subordinated or even excluded as relevant factors, as such criteria would not relate to the water column in the superjacent waters. In order to be considered a ‘special circumstance’ in this regard, something would have to be equally suitable for the seabed and the superjacent waters. Further to this the Court held:

It is, towards an application to the present case of criteria more especially derived from geography that it feels bound to turn. What is here understood by geography is of course mainly the geography of coasts, which has primarily a physical aspect, to which may be added, in the second place has a political aspect. Within this framework it is inevitable that the Chamber’s basic choice should favour a criterion long held to be as equitable as it is simple, namely that in principle, while having regard to the special circumstances of the case, one should aim at an equal division of areas where the maritime projections of the coasts of the States between which delimitation is to be effected converge and overlap.

Accordingly, in this case the Court favoured apportionment rather than delimitation in the context of a single maritime boundary for all purposes, and thus adopted the result-oriented equity approach. Yet, this was to change.

This understanding was upheld in the Guinea/Guinea-Bissau case of 1985, where the Court denied Guinea-Bissau’s contention of recourse to the equidistance method, saying that:

The Tribunal itself considers that the equidistance method is only one among many and that there is no obligation to use it or give it priority, even though it is recognized as having certain intrinsic values because of its scientific character and the relative ease with which it can be applied.

In the St. Pierre and Miquelon case of 1992, the Court reaffirmed the approach taken in the Gulf of Maine case, saying that the delimitation should be ‘effected in accordance with equitable principles, or equitable criteria, taking account of all the relevant circumstances, in order to achieve an equitable result. The underlying premise of this fundamental norm is the emphasis on equity and the rejection of any obligatory method.’

The 1993 Greenland/Jan Mayen case between Denmark and Norway differed from the three cases above in the sense that the Court was not asked specifically to draw up a single maritime boundary. Rather, the Court was asked to draw the boundary of the continental shelf and the fishery zone, and thus had to determine whether to apply the method of drawing a single maritime boundary, or to consider them separately. Norway argued that the boundaries should coincide but remain conceptually distinct, whereas Denmark asked for ‘a single line of delimitation of the fishery zone and the continental shelf.’ The Court affirmed Norway’s contention by stating that the Court was ‘not empowered or constrained by any such agreement for a single dual-purpose boundary.’ Accordingly, there was no law of coexistence of the boundaries, unless the Court had been asked specifically to draw them as such.

When we turn to the cases subsequent to the entry into force of the LOS Convention, that reasoning will be analysed as to whether that approach is still applicable by international law de lege lata. Examining this is important because the Court ended up drawing a coincident maritime boundary for the continental shelf and the fishery zone as in the previous cases, but now with a separate reasoning for each zone. The interesting thing about this approach is that the Court came to the same conclusion as in the previous cases without any reference to the ‘neutral criterion’ adopted in the previous cases involving a single maritime boundary. In this case the Court made its conclusion with reference to Article 6 of the Convention on the Continental Shelf as regards the delimitation of the continental shelf, and with reference to customary law of the EEZ for the delimitation of the fishery zone. If the parties had requested the Court to draw a single boundary, the ‘neutral criterion’ would have applied. And as a consequence the weight of access to fishery resources would have been minimized as it would not be relevant to the boundary of the continental shelf. Thus, had the Court been asked to draw single maritime boundaries, the end result might have been different.

In the Eritrea/Yemen case of 1999 the issue before the Court was once again to settle a single maritime boundary between the continental shelf and the EEZ. The relevant coasts were situated opposite each other; and, as mentioned earlier, the Tribunal considered that a median line would constitute an equitable maritime boundary in situations with opposite mainland coasts under Articles 74 and of the LOS Convention. In the Qatar/Bahrain case two years later, the Court decided that the same method was applicable under customary law for delimiting the single maritime boundary between states with adjacent coasts. This marked a shift in customary law from a situation in which any obligatory method was rejected and where maritime delimitation was conducted on a case by-case basis to achieve an equitable result, to a corrective/equity approach in which the court first draws a provisional median/equidistant line, and then inquires whether any special circumstances call for an adjustment of that line. (source: Pål Jakob Aasen, Fridtjof Nansen Institute)

The boundaries negotiated recently deal very often with an all-purpose delimitation line to cover both marine and sub marine areas (Venezuela- Trinidad and Tobago ( 1990)). The agreements based on a single line or “all-purpose line” currently number more than 50 and continue to grow, although considerations of oil deposits, for the continental shelf, or relating to fishing or navigation, for the exclusive economic zone, might call for different lines. Among those agreements are: Panama-Colombia ( 1976), France-Australia ( 1 982) and USSR-Finland (1985). However, some recent agreements deal with the continental shelf only, such as the Agreement between the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland and Ireland ( 1988).