Identification of Low-Tide Elevations

Article 13(1) of the LOSC defines low-tide elevations as follows:

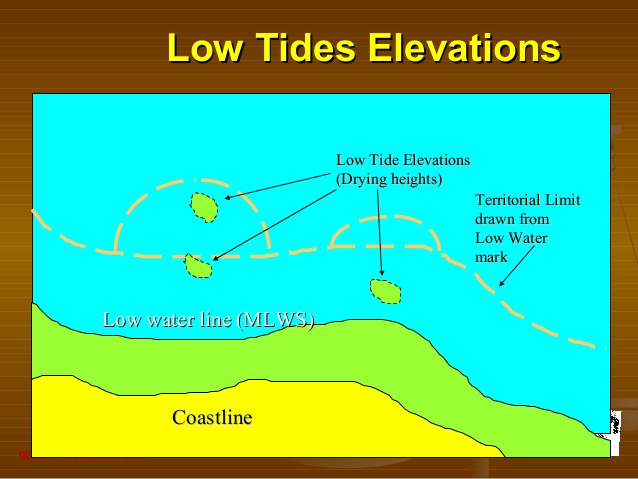

A low-tide elevation is a naturally formed area of land which is surrounded by and above water at low tide but submerged at high tide.

This provision further provides: ‘Where a low-tide elevation is situated wholly or partly at a distance not exceeding the breadth of the territorial sea from the mainland or an island, the low-water line on that elevation may be used as the baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea’. Where a low-tide elevation is wholly situated outside the territorial sea, however, it has no territorial sea of its own. The ICJ has held that Article 13 reflects customary international law. Considering that low-tide elevations may have an impact on identifying the outer limits of marine spaces under national jurisdiction, such elevations have practical importance for the coastal State.

In relation to this, a question that may arise concerns the identification of low-tide elevations. As the legal status of marine features may be changeable depending on the tidal datum in borderline cases, the selection of tidal datum is of central importance. However, no tidal datum was given in Article 11 of the TSC and Article 13 of the LOSC. In the United States v Alaska case of 1997, the Special Master’s Report indicated that ‘high tide’ was understood as ‘mean high water’ according to well-established United States practice.

The Supreme Court of the United States would seem to be supportive of this view. If the mean high tide is a well-established standard in the United States, this does not mean that it is an internationally accepted standard, however.

Despite attempts at international standardisation of the tidal datum, currently there is no uniformity in State practice in this matter. The situation is more complicated because States have used more than one datum along their coasts. It seems, therefore, that there are no customary rules concerning the use of tidal datum. It is also inconceivable that there are ‘general principles of law recognised by civilized nations’ on this issue. Thus, a dispute can be raised where the States concerned use different tidal datums, and the legal status of a marine feature differs depending on the datum. In this regard, three cases call for particular attention.

Case Law Concerning Low-Tide Elevations

The first case that needs to be examined is the 1977 Anglo-French Continental Shelf Arbitration. In this case, a dispute was raised between the United Kingdom and France with regard to the use of Eddystone Rocks as a base point in the delimitation of the English Channel.

The United Kingdom contended that Eddystone Rocks were to be regarded as islands and should accordingly be used as a base point for determining a median line in the English Channel west of the Channel Islands. Counsel for the United Kingdom argued that the Eddystone Rocks were only totally covered at high-water equinoctial springs, namely the highest tide in the year; and that they were uncovered at mean highwater springs, which was the required definition of an island in the United Kingdom Territorial Waters Order in Council of 1964, and was surely also in accord with international practice. Concerning tidal datum, the United Kingdom af firmed that, whether under customary law or under Article 10 of the TSC, the relevant high-water line was the line of mean high-water spring tides. In the view of the United Kingdom, the mean high-water spring tides was the only precise one, and the use of equinoctial high tide was not acceptable as sufficiently precise in this context. According to the United Kingdom, the height of the natural rock at the base of the stump of the old Smeanton lighthouse was approximately two feet above mean high water spring tide and 0.2 feet above the highest astronomical tide. Hence the United Kingdom alleged that Eddystone Rocks were not to be ranked as a low-tide elevation.

On the other hand, the French government contested the use of the Eddystone Rocks as a base point because it was not an island but a low-tide elevation. France argued that the British concept of ‘high-water’ was highly questionable and a large number of States, including France, took it as meaning the limit of the highest tides. France also claimed that, as soon as a reef did not remain uncovered continuously throughout the year, it had to be ranked as a low-tide elevation, not as an island.

The Court of Arbitration made it clear that the question to be decided was not the legal status of Eddystone Rocks as an island but its relevance in the delimitation of the median line in the Channel. It then held that France had previously accepted the relevance of Eddystone Rocks as a base point for the United Kingdom’s fishery limits under the 1964 – European Fisheries Convention as well as in the negotiations of 1971 regarding the continental shelf. For this reason, the Court of Arbitration accepted the use of Eddystone Rocks as a base point on the basis of estoppel. It may be said that the Court of Arbitration took a pragmatic approach leaving the status of Eddystone Rocks unresolved.

A second instance relating to low-tide elevations is the 2001 Qatar/Bahrain case (Merits). In this case, Qatar and Bahrain disputed whether Qit ’at Jaradah, a maritime feature situated northeast of Fasht al Azm, was an island or a low-tide elevation. According to Bahrain, there were strong indications that Qit ’at Jaradah was an island that remained dry at high tide. By referring to a number of eyewitness reports, Bahrain asserted that it was evident that part of its sandbank had not been covered by water for some time. According to the data submitted by Bahrain, at high tide, its length and breadth were about 12 by 4 metres, and its altitude was approximately 0.4 metres.

However, Qatar argued that Qit’at Jaradah was always indicated on nautical charts as a low-tide elevation. Qatar also insisted that, even if there were periods when it was not completely submerged at high tide, its physical status was constantly changing and thus it should be considered as no more than a shoal.

Having carefully analysed the evidence submitted by the Parties and the conclusions of experts, the ICJ held that Qit’at Jaradah was an island which should be considered for the determination of the equidistance line. Yet the reason why Qit’at Jaradah could be regarded an island, not a low-tide elevation, remains obscure.

A third case is the 2016 South China Sea Arbitration (Merits). In this case, a particular issue was raised with regard to evidence on the legal status of maritime features. According to the Annex VII Arbitral Tribunal, ‘[a]s a general matter, the most accurate determination of whether a particular feature is or is not above water at high tide would be based on a combination of methods, including potentially direct, in-person observation covering an extended period of time across a range of weather and tidal conditions’. However, many of the features in the South China Sea had been subjected to substantial human modification as large islands with installations and airstrips had been constructed on top of the coral reefs. In such circumstances, the Tribunal considered that the status of a feature must be ascertained on the basis of its earlier, natural condition, prior to the onset of significant human modification. The Tribunal therefore determined the legal status of maritime features on the basis of ‘the best available evidence of the previous status of what are now heavily modified coral reefs’. Specifically the Tribunal placed much weight on historical records when deciding the legal status of maritime features as above/below high tide. It then concluded that Hughes Reef, Gaven Reef (South), Subi Reef, Mischief Reef and Second Thomas Shoal are regarded as low-tide elevations.