Bays are of particular importance for coastal States because of their intimate connection with land. In this regard, the Arbitral Tribunal, in the 1910 North Atlantic Coast Fisheries case, stated:

the geographical character of a bay contains conditions which concern the interests of the territorial sovereign to a more intimate and important extent than do those connected with the open coast. Thus conditions of national and territorial integrity, of defense, of commerce and of industry are all vitally concerned with the control of the bays penetrating the national coast line.

Furthermore, where the low-water line rule applies to a bay whose mouth is less than twice the breadth of the territorial sea, the high seas may be enclosed within the bay. This situation will create inconvenient results for various marine activities. Hence, according to Gidel, it has been recognised that the baseline of bays for measuring the breadth of the

territorial sea is not the low-water mark. Indeed, the legal concept of a bay was admitted by the Institut de droit international in 1894 and the International Law Association in 1895, respectively. It could be said that customary law has allowed the coastal States to draw a closing line across the entrance of bays, whereby the landward waters from the closing line have become internal waters. In short, the legal concept of bays has emerged as an exception to the normal rule concerning the baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea.

The closing line of bays becomes the baseline for measuring the breadth of the territorial sea. Unlike the territorial sea, the right of innocent passage does not apply to internal waters. Should the waters of a bay be enclosed as internal waters, vessels flying the flag of a foreign State cannot enjoy innocent passage in these waters. The spatial scope of bays thus becomes a matter of important concern for shipping States. In this regard, the question that arises involves the criteria by which a coastal indentation can be recognised as a bay and the maximum length of the closing line across a bay. Concerning the latter, the 10-mile limit rule was applied by comparatively many treaties in the nineteenth and the early twentieth centuries.

Nonetheless, judicial practice was more cautious about accepting the customary law character of this formula. In the 1910 North Atlantic Coast Fisheries case, for instance, the Arbitral Tribunal did not consider the 10-mile formula as ‘a principle of international law’.

The legal nature of the 10-mile formula was also at issue in the 1951 Anglo-Norwegian Fisheries case. Although the United Kingdom asserted that the 10-mile formula could be regarded as a rule of international law, the ICJ refused to admit the customary law character of this formula. Overall it can be observed that customary international law has been

vague with regard to the maximum length of closing lines for bays. We must therefore turn to examine treaty law on this subject.

At the global level, the rules governing bays were, for the first time, set out in Article 7 of the TSC, and these rules were echoed essentially verbatim in Article 10 of the LOSC. This provision makes it clear that three classes of bays are outside the scope of its regulations.

First, Article 10 ‘relates only to bays the coasts of which belong to a single State’. Hence, bays bordered by more than one State are excluded from the scope of Article 10.

Second, historic bays are not regulated by Article 10(6) of the LOSC. As will be seen later, such bays are governed by a special regime.

Third, Article 10(6) provides that this provision does not apply to ‘bays’ where the system of straight baselines is applied. It is important to note that, legally speaking, the closing line across the mouth of a bay and the straight baseline are regulated by two different rules. In this regard, there is a concern that Article 10(6) can be used as an escape device to avoid rules regulating bays and to draw straight baselines across minor curvatures which are not strictly bays.

Article 10(2) then sets out geographical and geometrical criteria for identifying a bay.

Concerning geographical criteria, the first sentence of Article 10(2) provides:

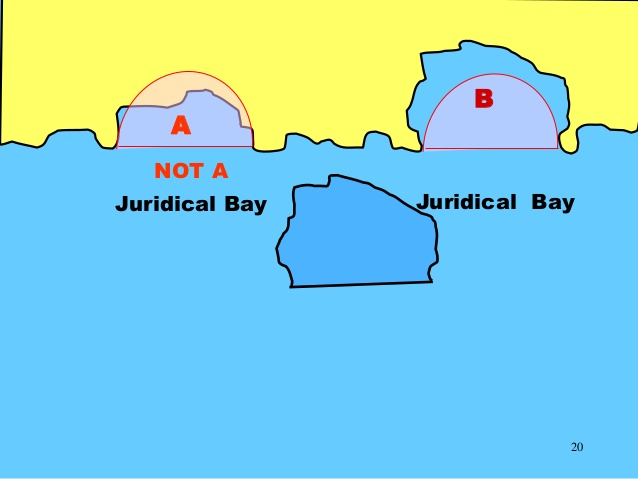

For the purposes of this Convention, a bay is a well-marked indentation whose penetration is in such proportion to the width of its mouth as to contain land-locked waters and constitute more than a mere curvature of the coast.

This provision contains two elements. First, a bay must be ‘a well-marked indentation’ and ‘constitute more than a mere curvature of the coast’. Second, the penetration of a bay must be ‘in such proportion to the width of its mouth’ and contain ‘land-locked waters’. It follows that the bay is surrounded on all sides but one.

With respect to geometrical criteria, Article 10(2) provides the semi-circle test:

An indentation shall not, however, be regarded as a bay unless its area is as large as, or larger than, that of the semi-circle whose diameter is a line drawn across the mouth of that indentation.

Article 10(3) further elaborates conditions in the application of the semi-circle test. First, Article 10(3) stipulates:

For the purpose of measurement, the area of an indentation is that lying between the low water mark around the shore of the indentation and a line joining the low-water mark of its natural entrance points.

A point that arises here is that it is not always easy to identify the natural entrance points of a bay. In fact, some bays arguably possess more than one entrance point that can be used.

Yet Article 10 contains no criterion for identifying the natural entrance points. In certain circumstances, the low-water line of a bay can be interrupted at the mouths of rivers flowing into the bay. Where the mouth of a river is wide and penetrated by tide, a difficult question arises as to how it is possible to calculate the area of the waters of the bay. This is particularly true in the situation where the area within the bay is very close to the area of the semi-circle.

Second, Article 10(3) provides:

Where, because of the presence of islands, an indentation has more than one mouth, the semicircle shall be drawn on a line as long as the sum total of the lengths of the lines across the different mouths. Islands within an indentation shall be included as if they were part of the water area of the indentation.

Where islands are situated seaward of the entrance to bays, however, the application of the semi-circle test is not free from difficulty.

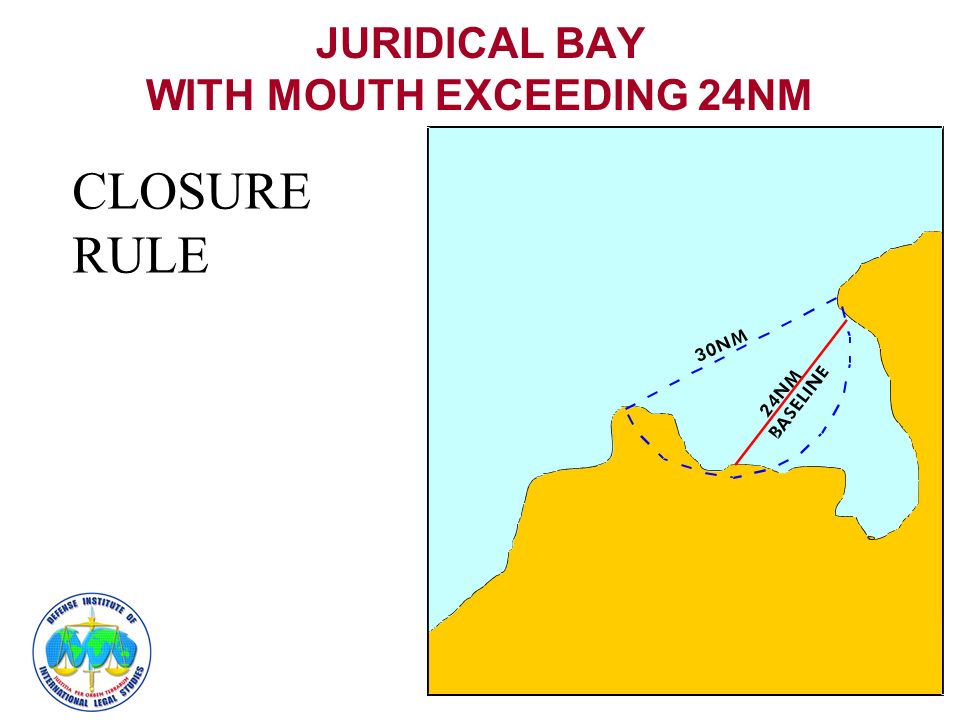

Third, unlike the method of straight baselines, Article 10(4) and (5) sets out a restriction of the maximum length of the closing line of a bay :

- If the distance between the low-water marks of the natural entrance points of a bay does not exceed 24 nautical miles, a closing line may be drawn between these two low-water marks, and the waters enclosed thereby shall be considered as internal waters.

- Where the distance between the low-water marks of the natural entrance points of a bay exceeds 24 nautical miles, a straight baseline of 24 nautical miles shall be drawn within the bay in such a manner as to enclose the maximum area of water that is possible with a line of that length. Obviously the 24-mile limit is based on the double territorial sea limit.

Overall it may be said that general rules determining the bays are currently established in the LOSC. Indeed, the ICJ, in the 1992 Land, Island and Maritime Frontier Dispute case, stated that ‘these provisions on bays might be found to express general customary law’.

source: The International Law of the Sea, Yoshifumi Tanaka