The first attempt at codification of the customary law of maritime delimitation started with the 1930 Hague Conference under the auspices of the League of Nations. The Hague Conference failed to reach its purpose and the following World War II period was not an appropriate period to deal with issues of maritime delimitation. In the aftermath of World War II, the creation of the United Nations Organization (UN) and the multiple individual claims of States over maritime spaces, such as the Truman Proclamation and the Santiago Declaration raised the need of re-starting the process of codification of the law of maritime delimitation. The adoption of the 1958 Geneva Conventions which followed was a successful initiative, at least to some extent.

The 1958 Geneva Conventions: Equidistance/Special Circumstances

The First United Nations Conference on the Law of the Seas, which was held in Geneva under the auspices of the United Nations from February 24 to April 27, 1958 adopted four important conventions. For the purpose of this study, the focus will be on the Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone and the Convention on the Continental Shelf. Article 12 of the Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone and article 6 of the Convention on the Continental Shelf are pursuant to the delimitation respectively of the territorial sea and the continental shelf. Both read as follows:

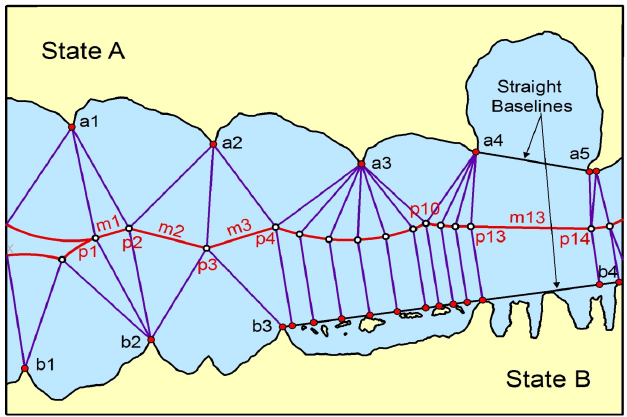

Article 12, Para 1: Where the coasts of two states are opposite or adjacent to each other, neither of the two states is entitled, failing agreement between them to the contrary, to extend its territorial sea beyond the median line every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points on the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial seas of each of the two States is measured. The provisions of this paragraph shall not apply, however, where it is necessary by reason of historic title or other special circumstances to delimit the territorial seas of the two States in a way which is at variance with this provision (see Figure 1).

And Article 6, Para 1: Where the same continental shelf is adjacent to the territories of two or more States whose coasts are opposite to each other, the boundary of the continental shelf appertaining to such States shall be determined by agreement between them. In the absence of agreement, and unless another boundary line is justified by special circumstances, the boundary is the median line, every point of which is equidistant from the nearest points of the baselines from which the breadth of the territorial sea of each State is measured (applies mutatis mutandi to the delimitation of two adjacent coasts pursuant to Para 2).

The drafting of both articles calls for an analysis. In the codification process of the law of delimitation of the territorial sea and the continental shelf, the 1958 Geneva Conventions adopted a triple rule “Agreement/Equidistance/Special Circumstances”.

In other words, understood as the process of determination of the jurisdictional ambit of two opposite or adjacent States on overlapping titles, any maritime delimitation shall be dealt with by inter-states negotiation and not unilaterally. In the absence of agreement, the applicable rule is the Equidistance/Special Circumstances rule, which has been given different meanings. First, it has been interpreted as a combined rule, i.e., equidistance or median-line is the starting point of delimitation; then, it is corrected to take account of specific circumstances peculiar to the geographical area if its rigid application is likely to cause some distortions. The intention to link equidistance and special circumstances as a combined rule was already expressed in the debate of United Nations Conference during the drafting of the delimitation provision as explained by the delegate of the United Kingdom.

On the other hand, the Equidistance/Special Circumstances rule has been interpreted as well in the ILC work as two separate rules; with equidistance being the general principle and special circumstances the exception. Therefore, in this context, any special configuration of the coast constituting special circumstances is no longer perceived as a corrective element of the equidistance line but as an exception justifying recourse to another method of delimitation.

The 1958 Geneva Conventions failed to provide an authoritative definition of “special circumstances”. The interpretation of this expression is based on the Travaux Préparatoires of the conference. According thereto, special circumstances mainly referred to islands, exceptional coastal geography, navigable channels, fishery and special mineral exploitation rights, and historic title.

The Equidistance/Special Circumstances rule must not to be confused with the Equidistance/Relevant circumstances principle born in another context as will be seen later. However, it is a major step towards the emergence of the Equidistance/Relevant Circumstances principle, the core subject of this thesis. Under the 1958 Geneva Conventions, the principle of equidistance had been codified, therefore, consolidated into a strict treaty law. In that way, equidistance has become a legal reference in matters of delimitation. The second remark is that the special circumstances express the imperfection of the equidistance principle, which may need to be deviated in order to secure an equitable result. However, the results achieved under the Equidistance/Special Circumstances were strongly challenged under the 1982 UNCLOS.

The 1982 UNCLOS: Equidistance v. Equity

The failure of the 1958 Geneva Conventions and the 1960 UN Conference (UNCLOS II) to settle issues related to the breadth of the territorial sea and the fishery limits, and the emergence of new debates on the exploitation of the international seabed area prompted the United Nations to convene States Parties for a Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III).

From April 1978 to August 1981, UNCLOS III was the forum, specifically in the Negotiating Group 7 (NG7), of a complex debate for the drafting and adoption of the new conventional law of maritime delimitation. It is worth noting that the orientation of the debate in UNCLOS III was deeply influenced by the recent development of the law of maritime delimitation as fostered by various case law, in particular the North Sea Continental Shelf case, and by major advances in the technologic development, which progressively rendered possible the exploitation of seabed and ocean floor for scientific, economic and military purposes. The Equidistance/Relevant Circumstances principle emerging at that time under case law, failed on two main aspects to be consolidated in the codification process under UNCLOS III.

In fact, the Equidistance principle codified under the 1958 Geneva Conventions was consolidated under UNCLOS III for the delimitation of the territorial sea (Article 15) but strongly challenged as far as the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf were concerned. Article 74, Paragraph 1 of the 1982 UNCLOS pursuant to the delimitation of the exclusive economic zone between States with opposite or adjacent coasts, which applies mutatis mutandi to Article 83 related to the delimitation of the continental shelf reads as follows :

The delimitation of the exclusive economic zone between States with opposite or adjacent coasts shall be effected by agreement on the basis of international law, as referred to in Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, in order to achieve an equitable solution.

Articles 74 and 83 provide the norm of international law governing any process of maritime delimitation. This should be governed by an agreement between the parties concerned either directly or by means of international judicial authorities, on the basis of legal principles developed under treaty law and customary law in order to achieve an equitable boundary line.

These provisions may be, however, considered as two “empty” rules since they fail to provide any specific method of delimitation of the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf. The reference to Article 38 of the ICJ Statute is also helpless insofar as this provision fails to specify any precise legal approach of maritime delimitation but allows for consideration of a broad range of applicable international laws.

The general wording of articles 74 and 83 of the 1982 UNCLOS was expressly set out during the conclusion of the debates in the NG7 in order to reach a consensus between the proponents of the Equidistance/Special circumstances, on the one hand, and the proponents of the equity/relevant circumstances on the other hand. Twenty two States (22) expressed themselves at the end of the debate in favour of the Equidistance/Special circumstances, and their proposal of delimitation under Articles 74 and 83, Para 1 reads as follows:

The delimitation of the Exclusive Economic Zone/Continental Shelf between adjacent or opposite States shall be effected by agreement employing, as a general principle, the median or equidistance line, taking into account any special circumstances where this is justified.

In contrast, the pro- equity/relevant circumstances group composed of twenty nine (29) States made the following suggestion:

The delimitation of the exclusive economic zone/continental shelf between adjacent or/and opposite States shall be effected by agreement, in accordance with equitable principles taking into account all relevant circumstances and employing any methods, where appropriate, to lead to an equitable solution.

Broadly speaking, a schematization of the debate could be featured as follows: on the one hand (1) agreement and (2) special or relevant circumstances as factors to be included in any delimitation process were the points of convergence between both groups. On the other hand, equidistance and equitable principles were the point of divergence. However, it is worth noting that at the conclusion of the debate, a dissension appeared between both opposite groups about the qualification of circumstances. The pro-equity group advocated for the relevant circumstances while the pro-equidistance group sponsored the special circumstances, as noted in the report on consultation on delimitation between delegations of two opposite groups.

Thus, challenged both for diverse reasons on what constituted the two pillars of the concept, i.e. equidistance on the one hand, and the relevant circumstances on the other hand, the concept of Equidistance/Relevant Circumstances was unable to emerge and be consolidated under UNCLOS III.