As the provisions of the LOS Convention on the marine scientific research

mainly deal with the rights and obligations between the coastal State and

the researching State and thus do not deal with the legal relations between

the two coastal States in the disputed areas, these provisions are not of

direct relevance in considering the question whether coastal State A can

conduct marine scientific research in the Disputed Areas without consent

from the other coastal State B.

It is to be noted that, as will be seen in Chapter 4, the Chinese exploration

activities in the East China Sea where there is no boundary sparked

off diplomatic rows with Japan as it regarded these exploration activities

by the Chinese vessels on the Japanese side of the hypothetical equidistance

line as an infringement on its rights. In this situation, the question

necessarily arises as to whether all scientific research or explorations by a

coastal State are not permitted at all in the disputed areas without consent

from the other coastal State?

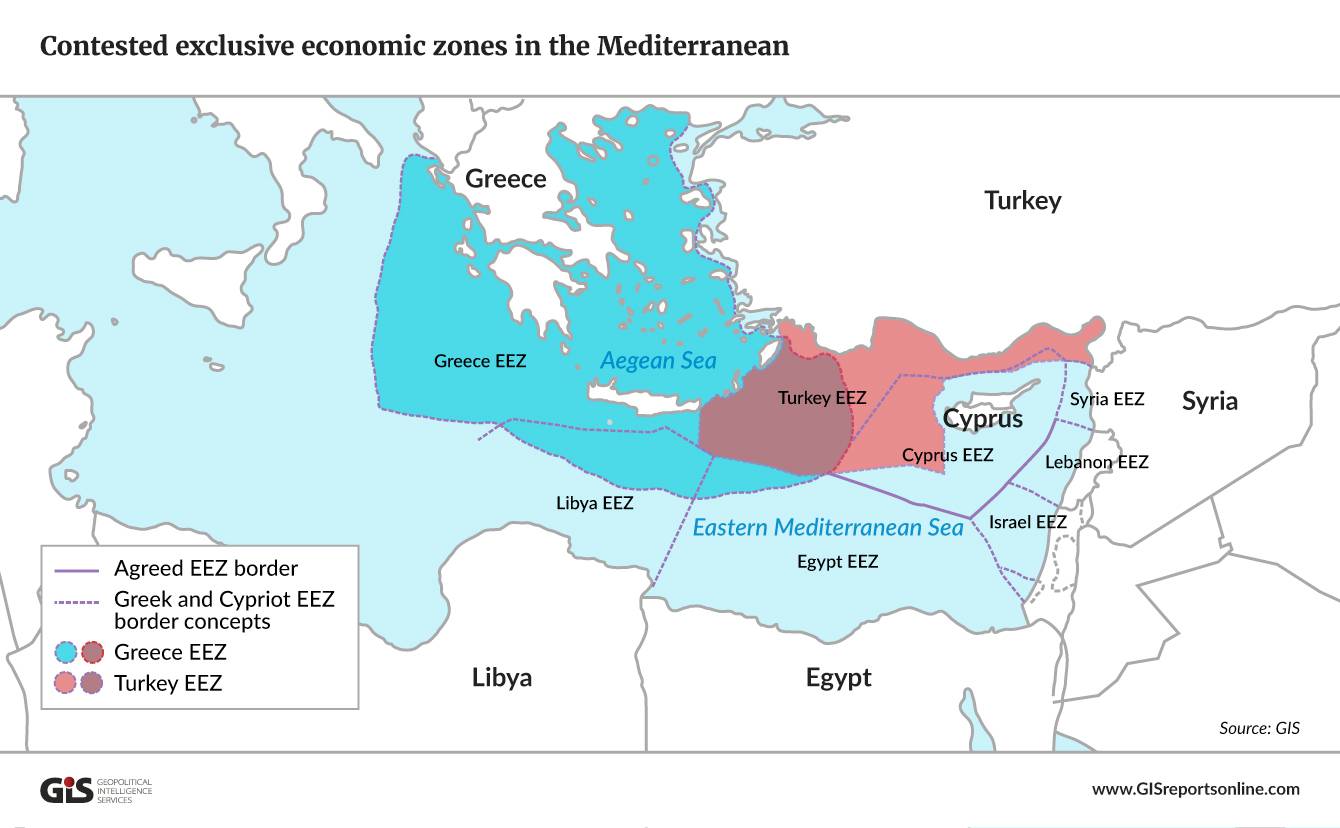

Interestingly, this question was raised in the Aegean Sea Continental

Shelf Case. In this case, Greece requested the International Court of Justice

to direct the two coastal States to refrain from all exploration activities or

any scientific research with respect to the continental shelf areas in dispute,

unless with the consent of each other pending the final judgment of the

Court. Greece argued that all unilateral exploration activities and scientific

research in the disputed area are not allowed because these might

prejudice the execution of any judicial decision.

If we read Greece’s argument carefully we can find that Greece tacitly

presupposes a genuine coastal State which has the sole exclusive sovereign

rights in the disputed area, when it argues that “the exclusivity of knowledge”

of the coastal State on its continental shelf should be protected. Along

this line of reasoning, Greece regarded any damages to exclusivity of knowledge

as irreparable damage to the rights of the coastal State, which should be protected by the ICJ until it declared that Greece is the coastal State, i.e., the genuine coastal State. Thus, Greece argued that, “Turkey’s grants

of exploration licenses and exploration activities must tend to anticipate the

judgement of the Court, and that breach of the right of a coastal State to

exclusivity of knowledge of its continental shelf constitute irreparable prejudice

(emphasis added)”. Greece went on to argue that:

. . . Turkey’s seismic exploration threatens in particular to destroy the

exclusivity of the rights claimed by Greece to acquire information concerning

the availability, extent and location of the natural resources of

the areas . . .

However, the Court did not agree on the concept of “exclusivity of knowledge”

of the genuine coastal State, but looked into the physical nature of

the activities undertaken by the other possible coastal State. For the Court,

seismic exploration was tolerable in the disputed area because it is merely

“of the transitory character” which does not involve “any risk of physical

damage to the seabed or subsoil or to their natural resources”. The Court

held that:

the seismic exploration undertaken by Turkey, of which Greece complains,

is carried out by a vessel traversing the surface of the high seas

and causing small explosions to occur at intervals under water; whereas

the purpose of these explosion is to send waves through the seabed so as

to obtain information regarding the geophysical structure of the earth

beneath it; whereas no complaint has been that this form of seismic exploration

involves any risk of physical damage to the seabed or to their natural

resources; whereas the continental seismic exploration activities

undertaken by Turkey are all of the transitory character just described,

and do not involve the establishment of installations on or above the

seabed of the continental shelf; and whereas no suggestion has been made

that Turkey has embarked upon any operations involving the actual appropriation

or other use of the natural resources of the areas of the continental

shelf which are in dispute . . .

With regard to the alleged damage to the exclusivity of rights to the information

on the natural resources, the Court held that:

Whereas, in the present instance, the alleged breach by Turkey of the

exclusivity of the right claimed by Greece to acquire information concerning

the natural resources of area of continental shelf, if it were established,

is one that might be capable of reparation by appropriate means,

and whereas it follows that the Court is unable to find in that alleged breach of Greece’s rights such a risk of irreparable prejudice to rights in

issue . . .

From the passage above, we find that the Court looked into the nature of

the exploration, to decide whether any unilateral exploration by one coastal

State is prejudicial to the rights of the other coastal State. If Turkey had

undertaken any actual drilling into the disputed continental shelf or actual

exploitation of oil or gas in the disputed area then the decision of the ICJ

would have been different. Therefore, it can be said that a coastal State can

conduct marine scientific research in the disputed area without consent from

the other coastal State as long as the scientific research is of the “transitory

character” which does not involve “any risk of physical damage to the

seabed or subsoil or to their natural resources”.

As the ICJ looked into the nature of marine scientific research and

made a distinction between the transitory character and non-transitory character

of the exploration, it might be appropriate to see whether there is such

a classification of marine scientific research in the provisions of the Geneva

Convention on the continental shelf and the LOS Convention.

We can see that the Geneva Convention makes a distinction between

“purely scientific research into the physical or biological characteristics of

the continental shelf” and other research and it provides that “the coastal

State shall not normally withhold its consent” with regard to such “purely

scientific research”. Although the Geneva Convention distinguished between

“purely scientific research” and other scientific research, it did not indicate

what this other research, which is not purely scientific, is. The other scientific

research which is not purely scientific appears to be that research

conducted for commercial or military purpose and thus can be referred to

as applied scientific research.

The reason why the Geneva Convention made a distinction between

purely scientific research and other research, appears to be that there was

a general view that the enhancement of knowledge about the ocean is for

the benefit of mankind as a whole. When François, the Special Rapporteur,

reported on the issue of scientific research in the eighth session of the

International Law Commission (ILC) in 1956, he introduced the resolution

of the International Council of Scientific Union (ICSU) on this issue, which

asserts that “fundamental research by any nation carried out with the intention

of open publication is in the interests of all” and the draft articles

should be amended so as to ensure “such fundamental research at sea may

proceed without vexatious obstruction”. Referring to the resolution of the

ICSU, the Special Repporteur stated his opinion that the coastal State will

not have the right to prohibit such purely scientific research.

In the resolution by the ICSU, we can see an illustration of purely scientific

research. In the resolution, this is “fundamental research in the geophysics,

submarine geology, and marine biology of the sea-bed and subsoil

of the continental shelf ”. Alfred H.A. Soons, having examined the drafting

history of the provisions, pointed out that:

The reference to purely scientific research was intended to make it clear

that the provision was not intended to cover exploration activities, i.e.,

the collection of data with a view to exploitation. Purely scientific research

can yield results which are useful from the point of view of exploitation,

but the research is conducted without paying attention to such practical

applications of the results. The reference to “physical or biological characteristics

of the continental shelf” was also intended to emphasise that

the research covered by the provisions excludes the collection of data

with a view of exploitation.

Let us turn to the LOS Convention to see whether there is a similar distinction

in the marine scientific research. The LOS Convention adopts basically

the same regime on the regulation of marine scientific research on the

continental shelf and in the exclusive economic zone as that of the Geneva

Convention. Under the LOS Convention, all scientific research on the continental

shelf and in the exclusive zone should be conducted with the consent

of the coastal State. The LOS Convention, like the Geneva Convention,

makes a distinction between two different kinds of marine scientific research;

one which is carried out “exclusively for peaceful purposes and in order to

increase scientific knowledge of the marine environment for the benefits of

all mankind” and the other scientific research. The discretion of the coastal

States with regard to the former type of marine scientific research is restricted

in the sense that the coastal States shall, in normal circumstances, grant

consent for marine scientific research of that type, whereas the coastal States

have discretion to withhold its consent with regard to the latter type of the

marine scientific research. Here we can associate the former type of the

marine scientific research under the LOS Convention with the purely scientific

research in the Geneva Convention.

The LOS Convention, unlike the Geneva Convention, elaborates what

the other scientific researches are, for which the coastal States can withhold

their consent. These other scientific researches are those which (a) are

of direct significance for the exploration and exploitation of natural resources,

(b) involve drilling into the continental shelf, the use of explosives or the

introduction of harmful substances into the marine environment, and (c)

involve the construction, operation or use of artificial islands, installations

and structures.

Having thus examined the provisions of the Geneva Convention and

the LOS Convention regarding the distinction between purely scientific

research and other research in the two conventions, an important question

arises here as to whether the distinction between pure scientific research

and other research adopted in the two conventions, have any relationship

with the distinction between the marine scientific research of transitional

character and of non-transitional character adopted by the ICJ in the Aegean

Sea Continental Shelf Case. If there is some relationship between the two

classifications, the provisions of Article 245 of the LOS Convention can also

be illustrative of what research activities by a coastal State A in the disputed

areas are prohibited without consent from the other coastal State B.

In fact, we can find a significant overlap between two ways of classification

by the ICJ and the LOS Convention. We can see that paragraph 5

of Article 246 of the LOS Convention lists several forms of research for

which the coastal State has discretion to withhold its consent. Furthermore,

we find there in the paragraph the very illustrations of explorations of a

non-transitory character which were mentioned by the ICJ in the Aegean

Sea Continental Shelf Case. Note that according to the ICJ, scientific

research is not of a transitory character if the research involves either (i)

“any risk of physical damage to the seabed or subsoil or to their natural

resources”, (ii) “the establishment on or above the seabed of the continental

shelf, or (iii) “the actual appropriation or other use of the natural resources

of the areas of the continental shelf which are in dispute”. Note that these

kinds of marine scientific research are provided for in paragraph 5 of Article

246 of the LOS Convention, for which the coastal State can withhold its

consent.

Here, we can see that the two concepts of the applied scientific research

in the LOS Convention and “exploration of transitory character” appear to

be almost the same in reality.200 Thus it can be presumed that a coastal State

would be ordered by the ICJ to cease the marine scientific research if it

involved the activities provided in paragraph 5 of Article 246 of the LOS

Convention in the disputed areas without consent from the other coastal

State.

By the same token, it can be said that the coastal State would not be

ordered to cease the purely scientific research conducted “exclusively for

peaceful purposes and in order to increase scientific knowledge of the marine

environment for the benefits of all mankind”, which does not involve any

of the activities provided for in paragraph 5 of Article 246 of the LOS

Convention.

However, it is not to be forgotten that even if one contending coastal

State can carry out some form of research activity in the disputed area, it is nevertheless expected to follow other rules applicable to scientific research, such as general principles for the conduct of marine scientific research provided

in Article 240 or the duty to publish and disseminate the information

and knowledge acquired from the research as provided in Article 244 of

the LOS Convention.

From the examination above, we can reasonably infer that some types

of marine scientific research can be conducted by a coastal State in the disputed

areas without consent from the other coastal State. However, the problem

is that there might be a situation where the coastal States have different

views on which research is permissible in the disputed areas without the

consent from the other contending coastal State. Or it might be the case

where one of the coastal States argues that any marine scientific research

in disputed areas without its permission is prejudicial to its rights. Therefore,

we can see that there is a clear need for neighbouring littoral States to talk

in order to have a common understanding as to which research can be conducted

in the disputed areas without the consent from the other coastal State

and to enter into arrangements for marine scientific research in the disputed

areas. It can be seen in Chapter 3 that there are several instances where

arrangements are in place in the disputed areas. These are the joint regime

area between Colombia and Jamaica, the common zone between Sudan and

Saudi Arabia and the common scientific and fishing zone between the

Dominican Republic and Colombia.