pursuant to article 76, paragraph 9, of the Convention of charts and relevant information, including geodetic data, permanently describing the outer limits of its continental shelf beyond 200 nautical miles in respect to the Barents Sea.

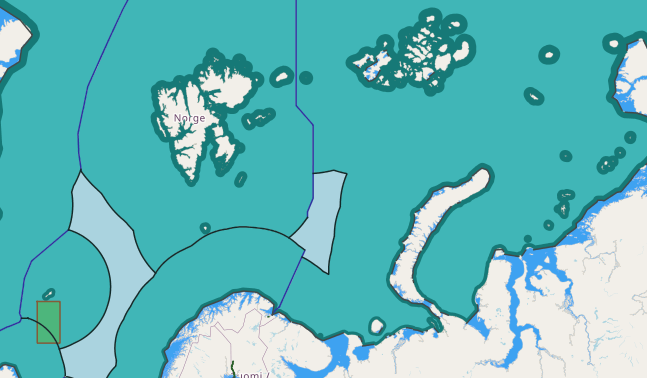

Russia-Norway: The Barents Sea, Svalbard/Svalbard

In 2010, after 40 years of negotiations, Russia and Norway settled a bilateral dispute over the maritime boundary and signed an agreement on the so-called “Grey zone” (175,000 sq. km.) on the shelf of the Barents Sea.

For Reference: The factors that have resulted in a compromise between Russia and Norway (Konyshev & Sergunin, 2014):

- Both countries have signed and ratified UNCLOS, which unified the national rules of delimitation of the continental shelf and EEZ (as the Convention provides identical rules based on the median principle, rather than the sectoral principle of demarcation of Sea territories);[1]

- Both countries took into account the decisions (a few in the 90 ‘s and 00 ‘s) of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on the principle of resolving sea disputes. The court determined that disputes should be resolved according to the principle of objective geographical factors, where there can be significant differences in the length of the coastline;

- Favorable political circumstances have emerged for Norway. This dispute was the last in the settlement of relations with Arctic neighbors, and in 2009 Oslo received a CLCS decision on the boundaries of its continental shelf and EEZ in the Arctic. It was important for Moscow to demonstrate goodwill and contractual capacity for a diplomatic fight with Denmark and Canada over the Arctic shelf;

- Both countries were interested in exploring the Barents Sea’s hydrocarbon resources

However, the signing of this agreement did not solve other problematic issues of bilateral Russian-Norwegian relations such as those regarding fisheries, energy production, and Russia’s desire to strengthen its presence in Svalbard/Spitsbergen.

The Arctic Continental Shelf

In defending its positions and interests in the Arctic in general and on the shelf in particular, the RF utilizes symbolic, legal, and military means. One of the brightest symbolic gestures was Russia’s placement of its flag on a titanium plate on the submarine ridge of Lomonosov in the North Pole in 2007.

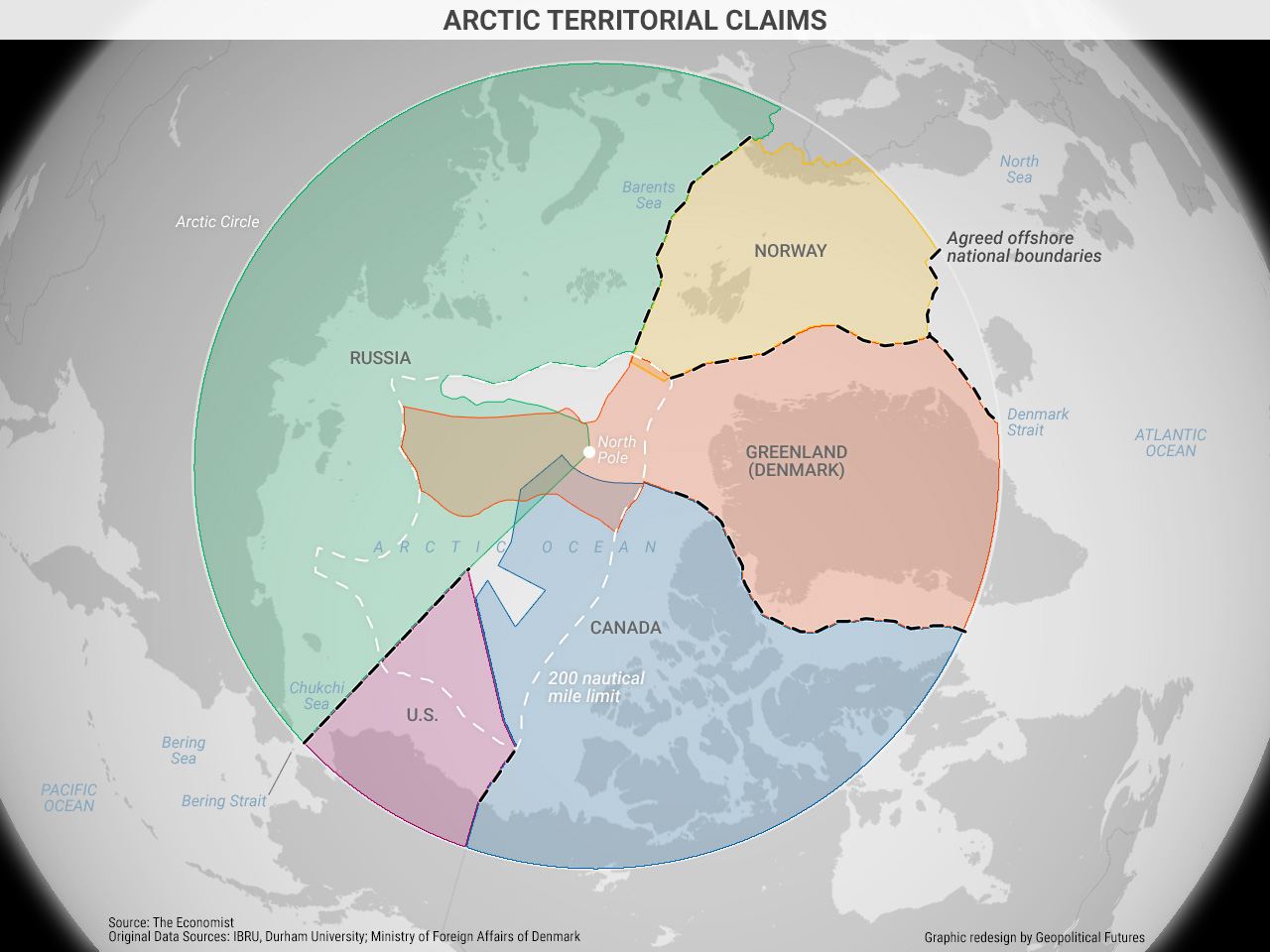

In the legal sphere, the RF is trying to assert its rights to the Arctic continental shelf through a mechanism of approval and the respective application of the UN Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf (CLCS). In 2016, Moscow submitted an updated and supplemented application for expansion of the border of the Arctic continental shelf by 1.2 million sq. km. (See Annex 2)

For reference: Russia’s opponents to this application are other Arctic states; Denmark, Norway, Canada and the United States. Denmark also claims to expand its own territory of the Arctic shelf by 900 thousand sq. km. Norway filed a request in 2006 and was the first to receive a positive decision by the Commission. Denmark submitted its application for consideration to the Commission in December 2014, and Canada in May 2019. The claims of Russia, Denmark, and Canada all partly intersect.

The issue of establishing national claims or sovereignty over the territory of the Arctic continental shelf is based on economic interests. Present in the disputed territories is approximately 13% of world oil reserves, 30% of gas reserves, and significant deposits of other useful minerals to include rare earth materials. Any solution to be found will be based not only on scientific evidence, but also on a political basis.

Experts predict various scenarios in the event that Russia’s application will be rejected by the Commission (Moe, 2011; Zagorskiy, 2013; Konyshev & Sergunin, 2014). The least probable scenario is the RF’s exit from UNCLOS and a unilateral declaration of Russian sovereignty on the expanded territory of the Arctic continental shelf. In this case, Russia will be in the U.S. position, outside of UNCLOS, and will rely on customary law and military force to substantiate its claims. It is believed that this is an extreme and unlikely step, since the positions of Moscow in this case would be weaker than the Commission’s decision. The second scenario involves reviewing their position and submitting a revamped, less ambitious, claim. This step will demonstrate respect for international law, but can provoke internal discussions within Russia. The third and most likely scenario, in the case of a negative decision, is to abandon the issue for a more favorable political circumstance and instead ensure Russia’s actual dominance over the region via military presence.

The important thing for Russia’s Arctic policy is that it is implemented by the RF as the sole presence in the region. Although other states declare their interest in the Arctic and protest against the spread of Russian sovereignty beyond the bounds of maritime law, there is no real competition for Russia’s presence there in the near term, although the first steps in this direction have been made by China. Therefore, the Arctic projects of the Russian Federation (NSR and continental shelf expansion) are a convenient opportunity for Moscow:

- To consolidate and secure the actual state of affairs until they become part of the legal order (customary law, tacit recognition).

- To strengthen the legal validity of the category of “historicity,” which is widely used by the Russian Federation to legitimize its interests and actions at sea and in other regions.

Both of these Russian policies are relevant to the Ukrainian-Russian confrontation. On one hand, Russia justifies its aggression and the illegal annexation of Crimea to the “historical affiliation” of these territories to Russia and lays the principle of “historical inland waters” for the Azov Sea in the legal field of Ukrainian-Russian relations. On the other hand, it tries to consolidate the Crimean situation in the international political field as the situation has developed.

Part of the Arctic policy of Russia is its relations with Norway in the Barents Sea and with the U.S. in the Bering Sea and Strait.